Part II: Undineiably a Fishy Story

Complex Creativity, Perhaps?

Many readers have thought of Goldberry as being a relatively simple character. Compared to Tom that seems quite true – at least superficially. But was there more to Tom’s bride than just a passing resemblance to classical nymphs (naiads and nephelai) of Greek myth? Did Tolkien stop right there and decide to limit Goldberry to purely Hellenic personifications of Nature? Or were there other facets to her invented essence, of a subtler complexion, requiring more intense deliberation and deeper exploration?

‘A Naiad’, John William Waterhouse, 1893

One needling matter that triggers further pondering is: ‘How did a wild and carefree water-being all but abandon an aqueous abode to firmly become a domesticated land-based wife’? How did she manage such a feat? There certainly are cases of akin creatures in Nordic, Teutonic and Welsh mythologies who managed to successfully transition, but the instances are rare. And so the question must be begged – did Tolkien follow established storyline patterns when shaping Goldberry? Or did the Professor create a new type of versatile life-form from that incredibly fertile mind?

To help answer all of these questions, we will need to examine several mythological archetypes from our world, ponder on their applicability, and then in finality try to thrash out whether Tolkien had an underlying purpose. Indeed, was there a ‘method to his madness’ or a ‘master plan’? However, before any postulation we need to remind ourselves that though the characters of Tom and Goldberry go hand in hand, Tolkien never plainly asserted they were hierarchically related beings. Nor, for that matter, did he spell out their entity class(es) within his own mythology.

Tom, in particular, has been a source of unceasing debate. Yes, his complexity has both intrigued and frustrated even the most studious of readers. Be that as it may, once we probe below the surface, it will become apparent Goldberry was no mere tag-along. Though textually much of her time was spent in the background – she was only a couple of sophisticated and equally enigmatic steps behind!

The Influence of Undine

Most interestingly, the Professor once gave away:

“I always in writing start with a name. Give me a name and it produces a story, not the other way about normally.”

– 1964 Interview with the BBC

Which story-wise resonates with Treebeard’s nature-related language:

“ ‘… Real names tell you the story of the things they belong to …’ ”.

– The Two Towers, Treebeard

Since, in all reasonableness, Part I lays bare the sources (and especially ‘thing’) behind her name, it’s time to pull together a fuller ‘story’ belonging to Goldberry. One far more complete and satisfying than already deduced. One that methodically and coherently binds the tale with our own world while explaining her wholesome character to a tee. Yet to expose the degree and depth of Tolkien’s imagination and inventive skill, I must focus on a particular type of ‘story’. To understand the ‘master plan’ we will be obliged to familiarize ourselves with fairy tales!

Now an interesting group of archetypes worth looking into that bear some similarity to aspects of Goldberry, and touched upon by Ruth Noel in The Mythology of Tolkien’s Middle-earth, are “the Undine, the Lorelei and the Siren”. Noel only casually addresses these mythical merwomen. But I shall dig deeper. Primarily the spotlight will be directed on the ‘undine’ (also known as the ‘ondine’).

‘Undine’, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Drawing by George Heywood Sumner

The fantasy writer George MacDonald, of whom Tolkien professed admiration1, once wrote:

“Read Undine: that is a fairytale … of all fairytales I know, I think Undine the most beautiful.”

– The Fantastic Imagination2, G. MacDonald, 1893 (italicized emphasis on first part of quote & ‘Undine’)

Published in 1811 and the work of German novelist: Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué – the tale of Undine was an established and quite beloved fairy-story by the late 19th century. Centered around a water-entity’s love for a mortal knight, it recounted how the creature (named Undine) married the man to gain a ‘soul’.

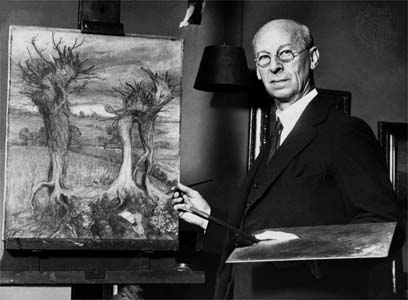

Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, 1777-1843

‘Well what has all this got to do with Tolkien’s Goldberry?’, one might ask.

In reply, I will say that the strands of web are circuitous – for the direct ones are missing. It is here we must pay heed to a convoluted, though not altogether fanciful, circle.

The popularity of Undine in Britain was great enough to allow the renowned English artist Arthur Rackham to illustrate a reissue in 1909. Tolkien much admired Rackham’s style and once admitted a drawing he had made of Old Man Willow:

“… probably came in part from Arthur Rackham’s tree-drawings …”.

– Tolkien: A biography, The storyteller – pg. 162, H. Carpenter, 1977

Arthur Rackham, 1867-1939

Rackham’s link to Bombadil went deeper than the Great Willow mention. Because Tolkien when doling out advice to Pauline Baynes, for illustrating The Adventures of Tom Bombadil booklet of 1962, brought in a comparison specifically naming the artist. Neither Arthur Rackham’s creative tone or Enid Blyton’s preferred style was optimal. But ‘caught between the Devil and the deep blue sea’ – the Professor preferred Rackham’s artistry:

“I have not much doubt, however, that you would avoid the Scylla3 of Blyton and the Charybdis4 of Rackham – though to go to wreck on the latter would be the less evil fate.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #235 – 6 December 1961, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

It seems reasonable to presume that Tolkien had decent familiarity with Rackham’s drawings. And not only that – awareness at the time work was initiated on The Lord of the Rings. Because Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull (per J.R.R. Tolkien Artist & Illustrator – pg. 156) confirm that ‘Old Man Willow’ (a tree drawing) was sketched for reference purposes at the time of writing The Old Forest chapter. Which for us, when we scrutinize it, is a matter5 of quite some importance!

‘Old Man Willow’ and the Withywindle River Setting, J.R.R. Tolkien

Nevertheless, there is no record of Tolkien ever having viewed Rackham’s illustrations in Undine. Even though a considerable collection of fairy-story books were purchased for his children6 – none have reported Undine among them. Nor has the book surfaced among the known remnants of the Professor’s personal library. So for us, the case is speculative – but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Because we can take comfort in salutary advice:

“… many facts that some enquirer would like to know are omitted, and the truth has to be discovered or guessed from such evidence as there is …”.

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #268 – 19 January 1965, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

Somewhere along the line, pre-1934 I am guessing, Tolkien ran across some Rackham art focalized on a particular water-maiden that ended up being wholly inspirational. Of course, given quality resources at his disposal and a vast housing at the University of Oxford’s multiple libraries, it is quite possible Undine was accessed therein. Equally possible is that C.S. Lewis introduced his friend to Rackham’s illustrations (and thus the fairy-story) given his acquaintance and delight7 with them:

“He loved the drawings of Arthur Rackham in Undine …”.

– Jack: A life of C.S. Lewis, Into Narnia – pg. 314, G. Sayer, 2005

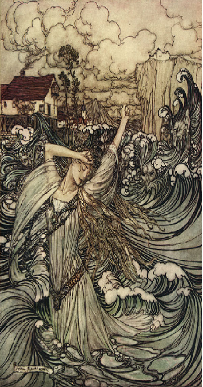

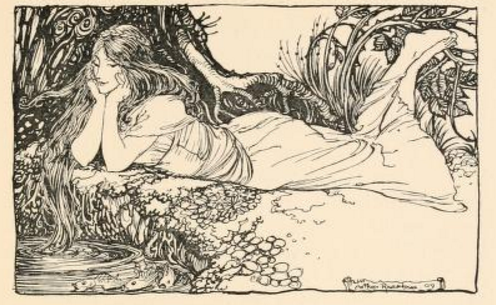

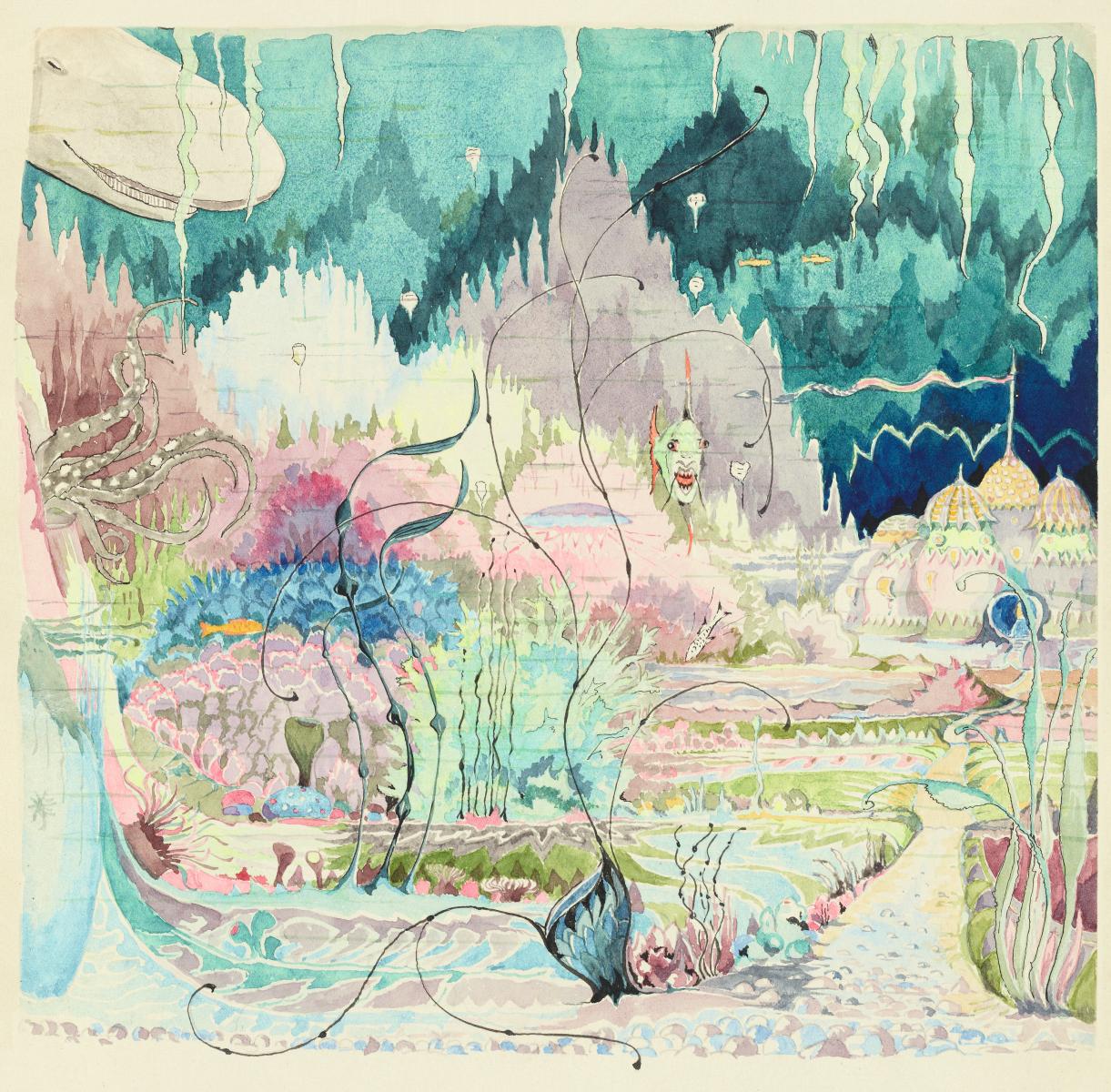

Five pieces of Rackham’s Undine artwork are shown below. All five of them have reasonable connectivity to Goldberry either in The Fellowship of the Ring or The Adventures of Tom Bombadil poem (1934 or 1962 version).

Painting 1

[Resonances: Gold belt, long rippling yellow hair, white arms, silvery colored clothes, house prominently positioned next to river waters per TLotR.]

Painting 2

[Resonances: Yellow hair, stone cottage positioned next to river waters, matching TLotR textual scene of Goldberry passing by a window.]

Painting 3

[Resonances: Yellow hair, greenish and silvery clothing, river abode below waters per The Adventures of Tom Bombadil.]

Painting 4

[Resonance: Dark stormy clouds*, TLotR textual scene of Goldberry out in the rain for her ‘washing day’.

* See Part I: nymph etymology, relation to nephos. The Nephelai (or Nephelae) were the Greek nymphs of clouds and rain.]

Drawing 5

[Resonance: Moment before capture by Tom beside the rushes of the Withywindle pool per The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and aired again in TLotR.]

Now before I go on to further discuss Undine, it must be emphasized that this writer is well aware of the pitfalls to definitively linking the preceding pictorial art of Rackham to Tolkien. Such dangers were outlined by the Professor himself in Letter #328 (from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Autumn 1971, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981). Some scholars will also no doubt point to Tolkien’s self-admitted weakness in remembering images and his preference for pure literature. Albeit Michael Drout in his Encyclopedia has noted the inconsistency of though:

“… declaring himself ‘not well acquainted with pictorial Art’. However, on other occasions he admitted a literary debt to visual art.”

– J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment, Artists and Illustrators’ Influence on Tolkien – pg. 37, M. Drout, 2007 (Tolkien’s words in single quotes)

In truth, as an owner myself of Rackham’s illustrated edition – with many of the pictures occupying an entire page – the eye cannot help but be drawn there. Rackham’s paintings and drawings are indeed magnetic and possess a unique charm. Partly my own personal experience lends me to believe Undine artistry might well have been subliminally or even consciously present in Tolkien’s mind at Goldberry’s conception – with a later rekindling for The Lord of the Rings.

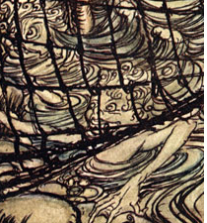

Yes, Rackham’s art has a distinct signature to its style. Once one spots a face in the surf – one cannot help but look for more. So it is the Professor’s invention of the “spirits of the foam and the surf of ocean” – the ‘Falmaríni and Wingildi’ per The Book of Lost Tales I8 (from a notebook created pre-1920) that perhaps leave the barest of vestigial clues. What source9 had given birth to the idea to include such rarely termed mythological beings? Their insertion makes me think Tolkien had encountered the Rackham edition of Undine well over a decade before our first introduction to Bombadil’s fair water-lady.

Four Faces in the foamy water – Excerpt from Painting 1 above

Two Faces in the foamy water – Excerpt from Painting 2 above

Another link of Undine to Tolkien appears at the outset of sharing his mythological writings to an audience of critical eyes. In 1920 after recounting The Fall of Gondolin to the University of Oxford’s Exeter College Essay Club, the recorder made the following note:

“… a discovery of a new mythological background Mr Tolkien’s matter was exceedingly illuminating and marked him as a staunch follower of tradition, a treatment indeed in the manner of such typical romantics as William Morris, George Macdonald, de la Motte Fouqué etc. …”.

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Note 5 to Letter #163 – 7 June 1955, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (my emphasis)

Ought not the documented reaction have piqued Tolkien’s interest? Wouldn’t he have wanted to read the official review?

As we can see it was highly positive. And thus one might infer, despite the passage of a century, Fouqué’s most famous tale (by far) had lost none of its charm among scholars of mythology and folklore. Counted alongside other notable romantics, perhaps we can glean that Tolkien already knew of Undine as a young adult!

Undine: A Paracelsian Elemental

Now the term ‘undine’ originates from mythological related theory advocated by a 16th century European alchemist and physician who went by the pseudonym ‘Paracelsus’. Its usage became so common that it became incorporated into all major dictionaries:

“Undine: a female spirit or nymph imagined as inhabiting water.”

– Oxford Dictionary of English, OUP, 2006

The word itself is sourced from Latin unda, meaning ‘wave’ or ‘water’. We know that Tolkien was familiar with this Swiss-German scientist’s pioneering work for at least two reasons. One being Tolkien mentions him in Letter #239 (from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, 20 July 1962, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981). The second is that Paracelsus was the inventor of the word ‘sylphs’ which Tolkien borrowed for The Lost Tales of the 1915’s – 1920’s. Hence, it seems reasonable to assume that he had become familiar, well before The Lord of the Rings, with what Paracelsus essentially described as ‘elementals’. Of course, if at this early time the term ‘sylph’ was known to a young Tolkien – undoubtedly ‘undine’ would also have registered.

As for ‘elementals’, they were posited to be unique life-forms each wrought from one of the four ancient elements: air, water, fire and earth. Except for the salamander, they took roughly humanoid shapes while subsuming the type of matter that they were associated to. Undines were of beautiful feminine appearance (when visible to mortals) and explicitly bonded to water – sometimes tailed and sometimes not.

‘The Untangling of Chaos’ or creation of the elements, God the Father stands astride a globe surrounded by the Universe, Hendrik Goltzius, 1589 Engraving

Despite a lack of scientific proof, Paracelsus was adamant such beings composed entirely of one category of matter:

“… were really living entities, … inhabiting worlds of their own, unknown to man because his undeveloped senses were incapable of functioning beyond the limitations of the grosser elements.”

– The Secret Teachings of All Ages, The Elements and Their Inhabitants – pg. 292, M.P. Hall, 1928

Fouqué built upon Paracelsus’s work and took it a step further. To Fouqué, water-nymphs and undines were equivalents:

“ ‘Pure and fair, more fair even than the race of mortals are the spirits of the water. Fishermen have chanced to see these water-nymphs or mermaidens, and they have spoken of their wondrous beauty. Mortals too have named these strange women Undines. …’ ”.

– Undine, F. de La Motte Fouqué, Project Gutenberg E-book, Editor: M. Macgregor, Chapter VII, 1907 (my emphasis)

Then were what Fouqué and we might term water-nymphs, really elementals? For Fouqué, we certainly can deduce so – for right at the end of the tale Undine reverts to her basic constituent fabric, that of water:

“… she went slowly out, and disappeared in the fountain. … a little spring10, of silver brightness, was gushing out from the green turf, and it kept swelling and flowing onward with a low murmur, till it almost encircled the mound of the knight’s grave; it then continued its course, and emptied itself into a calm lake, which lay by the side of the consecrated ground. Even to this day, the inhabitants of the village point out the spring; and hold fast the belief that it is the poor deserted Undine, who in this manner still fondly encircles her beloved in her arms.”

– Undine, F. de La Motte Fouqué, Project Gutenberg E-book, Introduction by C. Yonge, Chapters 9 & 10

More importantly had Tolkien latched onto such ideas? Had he thought of Goldberry in her river abode as not only akin to a classic Muse, but also an undine? Maybe there was a legitimate connection – because even in Roman and Greek mythologies – nymphs, on occasion, dissipate into water (see footnote 10). Then were water-nymphs and undines one and the same in the Professor’s mind too? Were they both ultimately elementals?

Whether so, I cannot prove. But there was one quality about a premarital Undine that is mirrored by her counterparts and captured so well in John Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs (picture depicted in Part I). Namely, outward youthful beauty – yet an accompanying inner coldness which is facially unmissable:

“Look deep into her blue eyes and you will see why her beauty is so cold, so chill. … In the eyes of every mortal you may see a soul. In the gay blue eyes of Undine, look you long and never so deep, no soul will look forth to meet your gaze.”

– Undine, F. de La Motte Fouqué, Project Gutenberg E-book, Editor: M. Macgregor, Introduction, 1907

‘Hylas and the Nymph’, Henry Pegram, erected in Regent’s Park, London 1933

(courtesy of Wikimedia)

In Fouqué’s tale11 the only way for an undine to gain a soul was to marry a man. Tom, though manlike in looks, was an immortal. But it is curious how per The Adventures of Tom Bombadil – just before marriage he found Goldberry by the rushes:

“… and her heart was beating!”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

Why wouldn’t it be? But was it merely fluttering in affection for Tom or was it the onset of a metamorphic transformation to acquire a soul? It might have been both, because in philosophy and mythology the heart, soul and love have always had strong linkage12!

Lily Transfiguration and the Breath of Immortality

To develop a more coherent theme, we must now turn to that branch of science covering water-flora. We must recall how from childhood Tolkien developed a strong interest in botany. Clearly such enamor was maintained into the late 1940’s as can be discerned by one of his walking friends’ observation of him being:

“… a fount of curious information about plants, …”.

– The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide 2017 Edition, Chronology, 5-9 August 1947

Some of that information likely included detailed knowledge of water-lilies – the so-called ‘water blobs’ of his childhood (see Part I). Once again it’s worth thinking about imagery and this kind of river-flora. If we do so, it isn’t hard to see why the heart-shaped leaf of the yellow water-lily has been a symbol since medieval times of true and pure love. An iconic manifestation of a river’s healthy soul – resulting ultimately from that most primeval of substances: water. And so, one might want to consider the effect Tom’s submersion had on the lily-pads after Goldberry pulled him into the water. Down he went:

“under the water-lilies, bubbling and a-swallowing.”

– The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, 1934 (& 1962) poem

Wouldn’t those bubbles in surfacing have made the lily-leaves pulsate like a living heart13? Was this part of the sequence instigating a mythical metamorphosis?

The Yellow Water-lily and its Heart-shaped Leaves (courtesy of Wikimedia)

Hmm … so from this mischief-making (or from the later capture event) was the truth behind the last step merely that a nearby yellow water-lily suddenly seemed to throb with life and then magically transfigure into a woman? In all the commotion is that what appeared to happen14?

And so … perhaps in the real world an akin event was what truly founded Teutonic interchangeability legends involving undines and Nymphæa water-lilies:

“According to German tradition, the Undines often conceal themselves from mortal gaze under the form of Nymphæas.”

– Plant Lore, Legends, and Lyrics, Nymphæa – pg. 463, R. Folkard, 1884

Perhaps Tolkien himself, in recalling his youth, had glimpsed the source of a metamorphosis myth in watching a fair-skinned, blonde and possibly long-haired15 Hilary emerge from lily-beds in Sarehole (or nearby) waters!

Then were such memories contributory to thoughts about his ancestors sighting those lesser gods and goddesses in rural lands? Had synthesized local produce and waters (infused for generations into their ‘blood and bones’) heightened audio-visual awareness of their surroundings? Perhaps it had … such that any unusual anomaly or oddity out in the countryside became acute to their senses. Thus, when no obvious explanation existed – could such phenomena, when the circumstances were right, be why rustic folk:

“… saw nymphs in the fountains …”?

– Letter from C.S. Lewis (quoting Tolkien) to A. Greeves, 22 June 1930

Later in life (but before The Lord of the Rings), had swimming among water-lilies16 in C.S. Lewis’s pond at the Kilns reminded him of childhood escapades? One can quite imagine how bathing in secluded semi-wilderness might just have triggered some stimulating chit-chat with his intellectual peer. Speculative conversation about how a stray traveler at the property boundary, espying them from afar, could perhaps mistake them for creatures other than human beings. Ultimately – in ancient times – could this be how merfolk legends arose?

The ideas are certainly compelling – but we mustn’t neglect a religious side to the Bombadillian poetic episode. In Christianity the ‘soul’ is equated to the ‘breath of life’. It constitutes the living and inhabiting yet incorporeal essence of a human being. The Catholic theologian Thomas Aquinas would have added further qualification by expanding ‘essence’ to ‘immortal essence’:

“… the LORD God formed the man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being.”

– The Bible (NASB 1995), Genesis 2:7

‘The Creation of Man’, Mosaic, Cathedral of Monreale, Sicily, Italy

Our modern-day word ‘soul’ stems from the ancient Greek word ‘psyche’: “to breathe”. Thus the source of this most age-old of concepts is buried deep in historical literature; leaving me to suspect that Tolkien purposely linked such roots to his own mythology. Bombadil wasn’t God – but his bubbles, I surmise, were the ‘fairy-story’ breath of life17. That sudden unleashing of a mythical spell. The classic point in a fairy tale upon which a water-nymph metamorphosed from a lily would acquire her eternal soul. Marriage to the ‘man’ who had breathed immortality into her was of course – inevitable!

So perhaps it is not at all of curiosity why the ending for the earliest full Bombadil poem resulted in matrimony:

“Old Tom Bombadil had a merry wedding, …”.

– The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, 1934 (& 1962) poem

Noticeably, wedlock was accompanied with a marked change in Goldberry’s character. From being mischievous, childish, even reckless – she became that perfect hostess: thoughtful and caring, while exhibiting elegant grace with measured wisdom. Such a u-turn, we must remember, was also part of the transformation process undergone by Undine in winning that ultimate prize:

“… the giddy, naughty, wayward, capricious, self-loving Undine, without a soul, contrasted with the calm, pious, consistent, self-denying Undine with a soul, …”.

– The English Review, Volume 3 – pg. 77, Undine, 1845

“… the contrast between the artless, thoughtless, and careless character of Undine before possessing a soul, and her serious, enwrapt, and anxious yet happy condition after possessing it, …”.

– The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Volume 3 – pg. 531, Marginalia, 1856

“The great charm of the tale lies in the sudden transformation of Undine on the day after her wedding, from the wild and wayward water-maiden into the sweet and gentle woman, out of whose eyes the newly-won soul looks forth.”

– The English Illustrated Magazine, Undine – pg. 307, 1887

Hmm – it is interesting to speculate on the lengths Tolkien went to in sourcing our favorite water-being for his early poetry, and then those ancillary tweaks and adaptations made for the later mythology. And more so, to examine the evidence and case for other elementals. An affirmative conclusion would strengthen Goldberry’s position in the hierarchy of mythological entities connecting ‘his world’ to ours. A hierarchy that perhaps has yet to be fully understood. However, such a discussion will be tabled for later.

The Popularity of Undine

As far as an opportunity arising to encounter the word ‘undine’ – it is quite possible, as a youth, Tolkien ran across it in Andrew Lang’s The Olive Fairy Book in The Story of Little King Loc:

“ ‘He is sitting in the palace of the Undines, under the great Lake; …’ ”.

– The Olive Fairy Book, The Story of Little King Loc – pg. 59, A. Lang, 1907

Issued a couple of years before ‘Rackham’s Undine’, there is little doubt Tolkien had read this fairy tale well before embarking on the Bombadil chapters in The Lord of the Rings. For indeed, he readily confessed that he had grown up with such literature – of which Lang’s books set the standard:

“In English none probably rival either the popularity, or the inclusiveness, or the general merits of the twelve books of twelve colours which we owe to Andrew Lang and to his wife.”

– The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, On Fairy-stories – pg. 114, HarperCollins, 1983

We should also observe that his preparatory notes for On Fairy-stories (see Tolkien On Fairy-stories, The Lecture by Verlyn Flieger & Douglas Anderson), 2014 made it quite plain that all twelve of Lang’s colored books had been surveyed before lecture delivery at St. Andrews in spring 1939. And it was around this time that Goldberry was being assimilated and shaped into his new fairy tale.

Now Arthur Rackham was not the only artist to visualize Undine. The popularity of Fouqué’s tale had spread across the Atlantic resulting in the heroine being physically immortalized by two of America’s greatest sculptors.

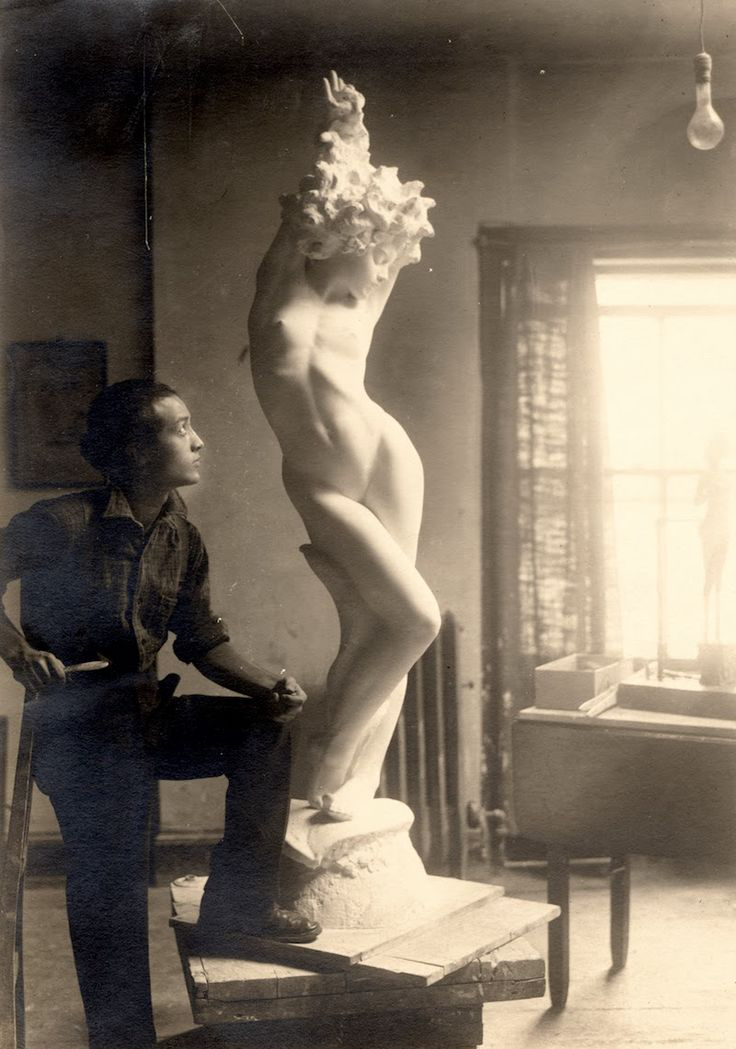

Isamu Noguchi with ‘Undine’, 1925

‘Undine Rising from the Waters’, Chauncey Bradley Ives, 1884

In terms of portraits, once again the name of John Waterhouse crops up. His enamor with the water-nymph propelled him to paint Ondine in the heyday of Pre-Raphaelite art.

‘Ondine’, John William Waterhouse – exhibited Society of British Artists, 1872

Clearly Fouqués’ story had embedded itself in the hearts of the English-speaking world by the turn of the 20th century. In America, the fairy tale had received rapturous acclaim by Edgar Allan Poe:

“What can be more divine than the character of the soul-less Undine? — what more august than her transition into the soul-possessing wife?”

– Review of Undine, Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, Review of New Books – pg. 173, September 1839, E.A. Poe

In England, the Royal Navy had named no less than five of its active ships HMS Undine by the time Tolkien graduated from the University of Oxford. Even a play had been written – notably connecting yellow water-lilies to the tale’s heroine:

“… Among the yellow lilies of the pool,

To greet me with thy kiss.”

– Undine: A Lyrical Drama – pg. 23, E.H. Moore, 1902

A couple of years before Rackham’s issue, another British artist named Katherine Cameron had illustrated Undine. The cover of a 1907 edition depicts Undine with a flower garland in her hair – presumably just like Goldberry at her wedding:

“… his bride with forgetmenots and flag-lilies for garland …”.

– The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, 1934 (& 1962) poem

‘Undine’, Friedrich de La Motte Fouqué, Cover by Katherine Cameron, 1907

And then preceding both Rackham and Cameron, the English artist Rosie Pitman had also taken a crack at drawing Undine inside a narrative. Against one of Pitman’s internally displayed drawings – the following comment was made:

“… a full blown water-lily, symbolical of Undine’s perfected and spotless soul.”

– Undine, F. de La Motte Fouqué, List of Illustrations – pg. xv, Illustrations by R.M. Pitman, 1897

Were the water-lilies gathered by Tom and brought to Goldberry intended symbolism too? A sign perhaps of another water-nymphs’ spotless and perfect soul? A ‘fairy tale’ soul which had ‘magically’ been acquired through breath, marriage and carnal union18?

“ ‘… Never mind your mother

in her deep weedy pool: there you’ll find no lover!’ ”

– The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, 1934 (& 1962) poem

Whatever the truth, going back to the major question posed at this article’s beginning – at least we have a reasonable mechanism for the transformation of a water-being to one fully at home on terra firma. In itself this is a vital step. For we must acknowledge Fouqué’s Undine is the closest model we have of a fairy tale creature upon which Goldberry might have been partly patterned. Yes, a metamorphosed aquatic entity Tolkien might have thought as being a link connecting the mythology of our real world to his feigned bygone Age.

Though we should not disregard the strength of the discussed peripheral clues, it is the sheer number of pictorial poses in the various issues of Undine which match up to details and hinted events surrounding Goldberry that is most remarkable. Though one cannot be certain, it appears this Germanic fairy-story attracted Tolkien’s attention. Enough to include its salient features into his own great tale.

Metamorphosis Myths and some Philological Connections

Now we must not forget that other examples exist within Tolkien’s own writings of interspecies marriage between a merwoman and a land-based ‘human’. Outside of his mythology Tolkien wrote in the 1920’s for his children the tale of Roverandom. Within a mishmash of folklore and legend, a mermaid princess marries the adventurous wizard (also described as a man) Artaxerxes. As with traditional myth – it was the mermaid who abandons the sea to live on land.

‘The Gardens of the Merking’s Palace’, Roverandom, J.R.R. Tolkien

Then sometime during his tenure at the University of Leeds Tolkien engaged in writing poetry in Old English about a mortal man who after falling into the sea, deserts his comrades and weds a mermaid. Published in Songs for the Philologists some pertinent lines from Ofer Widne Garsecg (Across the Broad Ocean) translate19 across as follows:

“ ‘I may not stay here any more, now separate from me!’

She said: ‘No, no, it will not be so! Now you will marry me.

Now go back again and say: “I’ll go on the high sea no more.

My wife is from the mermen near the deep sea-bottom.”’ “.

– Songs for the Philologists, Ofer Widne Garsecg, 1936

Indeed, we must observe such expansive waters are not so out of place when it comes to our river-maiden: Goldberry. Despite her known habitat being the minor largely placid waterway of the Withywindle tucked deep into Middle-earth’s countryside, we were made well aware that she knew the wide world possessed much vaster holding basins:

“… the clear voice of Goldberry … told the tale of a river from the spring in the highlands to the Sea far below.” (my emphasis)

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

In conveying a journey of birth, growth and eventually an illusory death – the reader was left to think about the omitted next step in Nature’s time-honored cycle. One where water from the sea, reshaped into vapor, would eventually fall as rain to complete the circle of rebirth. Effectively then, we have another metamorphosis.

Nonetheless, I believe the later thoughts she projected into the minds of all four hobbits conveyed more than just a physical journey. It was time to understand the spiritual side. This was a poignant moment to search within and reflect upon their own immortal souls. A gift, one must surmise, Goldberry was eternally grateful for. For joined into the tale was not only our world’s myth but academic material peculiar to Tolkien’s own field of interest. Into the mix, I have to conclude, Tolkien masterfully threw in some additional Teutonic ideas.

It was Tolkien’s great predecessor at the University of Oxford: Max Müller – Professor of Philology, who wrote about the soul’s Germanic links to ‘breath’ and the ‘sea’:

“Soul is the Gothic saivala20, and this is clearly related to another Gothic word, saivs, which means the sea. The sea was called saivs from a root si or siv, the Greek seiō, to shake; it meant the tossed-about water, in contradistinction to stagnant or running water. The soul being called saivala, we see that it was originally conceived by the Teutonic nations as a sea within, heaving up and down with every breath, and reflecting heaven and earth on the mirror of the deep.”21

– Lectures on The Science of Language, Knowing and Naming – pgs. 365-366, M. Müller, 1861 (my emphasis)

Compare Müller’s words I’ve underlined above against those of Tolkien22 below:

“… Goldberry sang many songs for them, songs that began merrily in the hills and fell softly down into silence; and in the silences they saw in their minds pools and waters wider than any they had known, and looking into them they saw the sky below them and the stars like jewels in the depths.”

– Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil (my emphasis)

And then lastly, adding to the Teutonic connection was more philological flavor. Goldberry’s expectant tarrying for a sky filled with stars appears to have been reminiscent yearning of her beloved pool, at dusk, studded with white water-lilies. Especially as there is meaningful interchange in Gothic naming for ‘lily’ and ‘star’:

“Waiting on the doorstep for the cold starlight, …”,

– The Fellowship of the Ring, The Old Forest (my emphasis)

“… A.S. tungol, Goth. /lily{71.9, ‘a star’} …”.

– Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics, Volume 12, Sun, Moon, and Stars (Teutonic and Balto-Slavic), J. Hastings/J. Selbie/L. Gray, 1951 (my underlined emphasis)

While Frodo’s song of a ‘waterfall’ linguistically linked in to Old High German:

“ ‘… O wind on the waterfall, …’ ”,

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil (my emphasis)

“Waterfall is in OHG. Wazarchlinga = nympha, …”.

– Teutonic Mythology, Vol. IV, Elements – pg. 1458, J. Grimm, translated by J.S. Stallybrass, 1883 (nympha being both a water-lily and water-nymph, my emphasis)

Hmm – so taking in combination these interconnected matters of: legendary water-maidens, bubbling lily-pads, the biblical breath of life, the winning of an eternal soul, metamorphosis, marriage to men, some initial thoughts on elementals and Teutonic philology – perhaps we can now head towards unraveling some of the mystery surrounding Bombadil’s little water-lady?

Yes … with the Professor, a name invariably generated a story:

“To me a name comes first and the story follows.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #165 – 30 June 1955, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

And what has been related is the background to a character befitting of masterly sub-creation. It is a ‘story’ that not only concerns Goldberry – but ultimately touches on human salvation. It is no wonder then, why the Professor stated the tale:

“… is mainly concerned with Death, and Immortality; …”.

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #211 – 14 October 1958, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

Goldberry supplied a unique aspect to that claim!

However, if I am mistaken and everything alleged in this ‘story’ is truly coincidental – then Goldberry herself might have told me to rapidly dismiss this train of thought and:

“ ‘… Make haste while the Sun shines!’ ”

– Fellowship of the Ring, Fog on the Barrow-downs

I however believe otherwise, and that there is no coincidence – only more purposeful linkage. I have this odd feeling Goldberry’s advice was just a donnish touch – a deliberate insertion of an undiffused forerunner of an ancient English idiom23:

‘Make hay while the Sun shines!’

For the next article in the series click below

Part III

Footnotes:

1 At least as far as his representation of goblins:

“George Macdonald, … has depicted what will always be to me the classic goblin. By that standard I judge all goblins, old or new.”

– Tolkien On Fairy-stories, Manuscript B, MS. 4, F 73-120 – pg. 250, V. Flieger & D. Anderson, 2014

2 Used as review material by Tolkien for his ‘Fairy Stories’ lecture and associated essay per Verlyn Flieger & Douglas Anderson’s Tolkien On Fairy-stories (Works cited or consulted by J.R.R. Tolkien), 2014. George MacDonald’s essay is brief (~one page) and the citation comes from the second paragraph – virtually at the article’s beginning. With the added italicized emphasis – it is very hard to miss. MacDonald’s view ought to have intrigued Tolkien – at the (unknown) point he first ran across it.

Though failing to make mention, it is quite possible Tolkien had in mind Undine’s influence on MacDonald when opining that:

“Death is the theme that most inspired George MacDonald.”

– The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, On Fairy-stories – pg. 153, HarperCollins, 1983

3 The sea monster was originally a sea nymph loved by Poseidon. From this mention (and Charybdis below in footnote 4) we might infer Tolkien was well-acquainted with Greek mythology pertaining to nymphs.

4 The sea monster was originally a sea nymph, daughter of Poseidon.

5 The season depicted in the drawing probably corresponds to the onset of autumn per the hobbits’ visitation in The Old Forest chapter. Quite bare willow branches and yellow leaves beginning to shed in quantity lend us reasonable clues.

Barely discernible on the right-hand side of the picture (in the river) are three single green stems atop of which are yellow flowers; while adjacent to each stalk floats a broad leaf. Because the stems are located reasonably far in the flow (i.e. they are not riverbank flora) – one might deduce that Tolkien sketched in some yellow water-lilies (perhaps the last of the season), leaving a trace clue that this river-plant, as proposed in Part I, was on his mind.

Excerpt from ‘Old Man Willow’

6 Ample bestowals can be gleaned from:

“I have given My Children have had many fairy-story books … usually given them by others in accord with tradition.”

– Tolkien On Fairy-stories, Manuscript A – pg. 186, V. Flieger & D. Anderson, 2014

7 C.S. Lewis started reading Arthur Rackham’s illustrated edition of Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué’s Undine in 1916. In 1917 correspondence with his friend Arthur Greeves he wrote about his admiration for Rackham’s drawings. Also stated was a desire to obtain his own copy – though it hasn’t surfaced in the archives of his personal library mainly housed at Wheaton College, Illinois.

8 There is also a naming resemblance of Undine/Ondine to Tolkien’s Uinen/Onen in The Book of Lost Tales I preceding The Lord of the Rings (it appears Uinen developed from Ui – Queen of the Mermaids per the early Qenya Lexicon; eventually Uinen became a Maia of the seas and oceans). The naming similarity is too striking to ignore – and again hints at Tolkien possessing early knowledge of Fouqué’s fairy tale.

Tolkien in The Book of Lost Tales I refers to three distinct groupings associated to the Vala Ulmo. Mermaids appear to have fallen under Oarni. No explicit explanations or bodily descriptions were given to the long-tressed Wingildi* and Falmaríni – beyond their association to waves, surf and foam.

9 A possible literary source is King Lear of William Shakespeare fame. Sir Israel Gollancz analogized:

“King Lear is Neptune, the Scandinavian and Celtic Neptune, and the rough, heartless daughters are the fierce waves, and the gentle Cordelia the mild wave.”

– Tolkien Studies 14 – pg. 24, The Mystical Philology of J.R.R. Tolkien and Sir Israel Gollancz, H.L. Spencer, 2017

10 Transformation of an embodied nymph to pure water was probably inspired by the mythology in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (Cyan melts into water – Book V, Hyrie turns into a spring – Book VII and Egeria turns into a spring – Book XV).

For Tolkien’s likely knowledge of Ovid/Metamorphoses – see Jason Fisher’s Tolkien and the Study of His Sources, Sea Birds and Morning Stars (Larsen), 2011.

11 The story’s plot also appears in Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid where another type of merwoman similarly gains a soul by marrying a mortal:

“A mermaid has not an immortal soul, nor can she obtain one unless she wins the love of a human being. On the power of another hangs her eternal destiny.”

– Hans Andersen’s Fairy Tales, The Little Mermaid – pg. 230, H.B. Paull, 1867

‘The Mermaid’, Stories from Hans Andersen, illustration by Edmund Dulac, Hodder & Stoughton, 1911

Her doom, like Undine’s, was to revert to ‘element’ form if she failed:

“ ‘… when we cease to exist here we only become the foam on the surface of the water, …’ ”.

– Hans Andersen’s Fairy Tales, The Little Mermaid – pg. 220, H.B. Paull, 1867

Some fifty years later Oscar Wilde published The Fisherman and his Soul. In that case, Wilde’s twist demanded the fisherman relinquish his soul to win a mermaid’s love.

12 For example, Aristotle placed the location of the soul in the heart; while Plato subdivided the soul into three parts/placements:

logos (head), thymos (lungs) and eros (heart).

13 Indeed, one species of yellow water-lily: Nymphoides peltata, is called the ‘floating heart’ – again, specifically because of the shape of its leaf.

14 The presented analysis presumes that Tolkien had this angle in mind during construction of The Adventures of Tom Bombadil poetry. What is certain is that Tolkien knew of the yellow water-lily and had an immense interest in both flora and Greek legends by early adulthood. His “most treasured book” details the plant’s connection to the mythical water-nymph, and we can be almost sure that he knew of a nymph to water-lily transformation process through his possession of The Life and Death of Jason, 1867 by William Morris.

An echoing of such matters in Tolkien’s poetry is quite probable, for such verse is likely to have had more scholastic depth than readers have understood. This poem may well have been an attempt to ‘anglicize’ some famous Greek legends (including Eros & Psyche* as well as Persephone & Hades). It may also have been written as a response to Owen Barfield’s Poetic Diction, 1928. Further explanations and analyses will be provided in a future article.

* Which Tolkien certainly knew. See The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, On Fairy-stories – pg. 119, HarperCollins, 1983.

15 Noted in Tolkien: A biography, Birmingham by Humphrey Carpenter: the two brothers were subject to mockery, by other Sarehole children, because of their long hair and pinafores. An interview with a newspaper provides affirmation:

“ ‘They rather despised me because my mother liked me to be pretty, I went about with long hair …’ ”.

– The Oxford Mail, 3 August 1966

16 No absolute proof exists that water-lilies were present on the occasions Tolkien swam with Lewis:

“… The Kilns, a house at the foot of Shotover Hill, … had a pond where Jack and Tollers would go swimming in the summer.”

– A Brief Guide to J.R.R. Tolkien, The Inklings, N. Cawthorne, 2012

However the following excerpt, I would guess, is probably based on Lewis’s personal experience at the Kilns’ pond:

“In a pond whose surface was completely covered with scum and floating vegetation, there might be a few water-lilies.”

– Miracles, Nature and Supernature – pg. 38, C.S. Lewis, 1947

A view of the pond at The Kilns

17 Perhaps the best example can be found in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, 1950 by C.S. Lewis. The scenes where Aslan breathes on the stone Narnians restoring them to living beings, symbolize the Genesis story.

18 I suspect that Tolkien felt there was more than just a connubial aspect to gaining a soul. Sex was traditionally a taboo subject for fairy tales – yet nevertheless an implicit part of a conventional marriage.

19 See The Road to Middle-earth, Appendix B – pg. 360, 2003 by T.A. Shippey.

20 The English cognate to the Gothic saivala and Old Saxon sêola (Old High German: sêula, sêlaare) appears as the Anglo-Saxon: sáwol, sáwel. Tolkien would have been particularly interested in such etymology as sáwel occurs in Beowulf.

It was Josef Weisweiler in his paper titled Seele und See (1940) who formally proposed that a common source* of ‘saiwlo – soul and saiwaz – lake, sea’ resulted from a Germanic folklore belief that new souls arose from such waters.

One can readily see how in the distant past Teutonic myth might have become muddled. What legend was closer to the ‘truth’? Newly formed souls emerging from a lake or instead a soulless Undine abandoning her lake in search of immortality? In weighing matters – Tolkien, if asked, may well have preferred the latter!

* Tolkien may have run across the concept from the definition of ‘soul’ in Walter Skeat’s authoritative philological standard:

“… the striking resemblance between Goth. saiwala, soul, and saiws, sea, suggests a connection between these words.”

– An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language, ‘Soul’ – pg. 575, W. Skeat, 1888

Rachel Fletcher in Tolkien’s Work on the Oxford English Dictionary: Some New Evidence From Quotation Slips (see Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 10 Issue 2 Article 9, 2020) has demonstrated Tolkien made extensive use of Skeat’s dictionary early in his career.

21 An extension to Max Müller’s statement can be found in another of his works:

“… it was the simple story of nature which inspired the early poet, and held before his mind that deep mirror in which he might see reflected the passions of his own soul.”

– Chips from a German Workshop*, Volume 2, Comparative Mythology, M. Müller, 1874

One might surmise that when it came to The Lord of the Rings, it was Goldberry’s narrative-songs about Nature that enchanted the hobbits to the point of allowing them to ‘glimpse’ their own souls within.

* Tolkien consulted Volumes 1-4 for his On Fairy-stories essay and associated lecture of 1939 per Verlyn Flieger & Douglas Anderson’s Tolkien On Fairy-stories (see Works cited or consulted by J.R.R. Tolkien), 2014.

22 Tolkien was never one to lift wholesale – complete sentences or paragraphs from the works of others (with the exception of short phrases or proverbs whose origins could not be attributed with certainty). An active dislike of plagiarism is reflected, I believe, in a parody hidden in The Root of the Boot (see Tudor, Elizabethan and Jacobean Connections – Part I). Reconstitution in a form whereby the original work was still recognizable – appears to have been the Professors’ style.

23 The phrase is first recorded by the Elizabethan John Heywood. His importance in Tolkien’s mythology will be spelled out a later point (Tudor, Elizabethan and Jacobean Connections – Part I) in this contiguous train of articles.

Revisions:

Grammatical, spelling and minor error corrections are not recorded. Neither are minor changes to phrasing that have little bearing as to the thrust of the message being conveyed by the author.

All revisions prior to 2020 are archived. Please contact the author if records are required.

1/31/20 Added: “and decide to limit Goldberry to a purely Hellenic personification of Nature?”.

Added: “Ought not the documented … one might infer,”.

Added: “, as a youth,”.

Was: “The season depicted in the drawing is not clear. It probably corresponds to autumn per the hobbits’ visitation in The Old Forest chapter.”, Is: “The season depicted in the drawing probably corresponds to autumn per the hobbits’ visitation in The Old Forest chapter. Bare willow branches and yellow leaves beginning to shed in quantity lend us a reasonable clue.”.

Added: “Indeed he had grown up … We should also observe that”.

Added: “Though one cannot be certain … features into his own great tale.”.

Added: “Perhaps Tolkien himself, … Greeves, 22 June 1930”.

Added: “In conveying a journey … circle of rebirth.”.

Added: “It was time to understand the spiritual side.”.

Added: “It is no wonder, … aspect to that claim.”.

Added: “For Tolkien’s likely knowledge … Sea Birds and Morning Stars (Larsen).”.

Added: new footnote 8, reordered existing.

2/10/20 Was: “watching Hilary”, Is: “watching a fair-skinned, blonde and possibly long-haired9 Hilary”.

Added: new footnote 9, reordered existing.

3/5/20 Added: “the biblical breath of life”.

Added: “(and thus Rackham’s illustrations)”.

Was: “Tolkien – I think, chose the latter!”, Is: “Tolkien, if asked, may well have preferred the latter!”.

Added: “To develop a more … and river-flora”.

4/11/20 Added: “* Tolkien may have … W. Skeat, 1888”.

4/16/20 Added: “per The Adventures of Tom Bombadil – just before marriage”.

4/23/20 Added: “* See Part I: nymph etymology, … of clouds and rain.”.

Added: “And then lastly, adding to the Teutonic connection … water-lily and water-nymph, my emphasis)”.

5/4/20 Added picture of water-lily against a starry sky.

Added excerpt from ‘Old Man Willow’.

6/7/20 Added: “Later in life … how a legend arose?”.

Added: new footnote 10, reordered existing.

Added: A view of the pond at The Kilns.

8/21/20 Added: new footnote 3, reordered existing.

8/25/20 Was: “Neither Rackham’s or Blyton’s creative tones”, Is: “Neither Arthur Rackham’s creative tone or Enid Blyton’s preferred style”.

9/20/20 Was: “though some might view fanciful”, Is: “though not altogether fanciful”.

Was: “foam-maidens and foam-fays”, Is: “spirits of the foam and the surf of ocean”.

Added: “What source had given birth to the idea to include such rarely discussed mythological beings?”.

Added: “To Fouqué, water-nymphs and Undines were equivalents:”.

Added: “Tolkien in The Book of Lost Tales I refers to three distinct groupings … Falmaríni represented – beyond their association to waves, surf and foam.”.

Added: new footnote 14, reordered existing.

10/14/20 Added: “And it was around this time … shaped into his new fairy tale.”.

10/27/20 Added: “Which, for us, is a matter2 of quite some importance!”.

Added: “With the Professor, a name … touches on human salvation.”.

11/25/20 Added: “Were they both ultimately elementals?”.

12/15/20 Added new footnote 1, reordered existing.

12/20/20 Was: “Was such a scenario partially behind why he felt that his ancestors with deep affinity to the lands for generations”, Is: “Then were such memories contributory to his ancestors … circumstances were right, be why rural folk:”.

1/16/21 Added new footnote 7, reordered existing.

1/26/21 Added: “Which story-wise resonates … The Two Towers, Treebeard”.

3/5/21 Added photograph of Hylas and the Nymph.

Was: “As far as when Tolkien first encountered the word ‘undine’ – it is quite possible, as a youth, he”, Is: “As far as an opportunity arising to encounter the word ‘undine’ – it is quite possible, as a youth, Tolkien”.

Was: “For indeed he had grown up with such literature.”, Is: “For indeed he readily confessed that he had grown up with such literature, of which Lang’s books set the standard:”.

Added quote: “In English none … Andrew Lang and to his wife.”.

4/14/21 Added new footnotes 3 and 4, reordered existing.

12/8/21 Added: “(and especially ‘thing’)”.

Added: “Though failing to make mention,”.

2/17/22 Added new footnote 14, reordered existing.

6/15/22 Added: “Rachel Fletcher in … early in his career.”.

8/7/22 Removed all section breaks: “*****”. Added sub-section titles, 6 places.

11/30/22 Added: “Fouqué built upon Paracelsus’s work and took it a step further.”.

2/26/23 Added: “An interview with a newspaper provides affirmation:”, followed by quote from The Oxford Mail.

2 thoughts on “Goldberry: The Enigmatic Mrs Bombadil”

Comments are closed.