Introduction:

What follows begins a four-part series that advances and discusses a wholly new approach to looking at Tom Bombadil’s mysterious lady: fair ‘Goldberry’.

Part I: Names, Nymphs and Nature’s Lilies

Etymology and the Yellow Berry

When it came to origins and sources Tolkien clarified that for The Lord of the Rings:

“The etymology of words and names in my story has two sides: (1) their etymology within the story; and (2) the sources from which I, as an author, derive them.”

– Letter to G. Wolfe from Tolkien, 7 November 1966

Later he confirmed the stimuli behind item (2) names lay:

“… exterior to the story, …”.

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #297 – August 1967, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (Tolkien’s italicized emphasis on ‘exterior’)

Now according to notes in a booklet of poetry issued after The Lord of the Rings, ‘Tom Bombadil’ as a name ‘within the story’ was likely hobbit inspired – being:

“… Bucklandish in form …”.

– The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, Preface, 1962 (available in The Tolkien Reader)

However, we know through the 1934 The Adventures of Tom Bombadil1 the Professor:

“… had already ‘invented’ him independently …”,

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #153 (draft) – September 1954, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (Tolkien’s emphasis)

and prior to commencing The Lord of the Rings.

Because the name had been originally assigned to a toy2, we can also reasonably infer that it arose from outside of the Silmarillion mythology. Moreover, that it was Tolkien himself who had come up with it:

“… I should not have given him so particular, individual, and ridiculous a name …”.

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #153 (draft) – September 1954, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (my emphasis)

But what ‘exterior’ factor prompted such a ludicrously sounding and unique title is far the more interesting question.

Mark Hooker’s groundbreaking thesis: Magnus Thomas Bombadilus Oxoniensis in The Hobbitonian Anthology is perhaps the closest we can currently get to nailing down the out-of-mythology source of ‘Tom Bombadil’. In short, Hooker theorizes that ‘Tom’ was derived from Oxford’s renowned Christ Church College Tower bell – known as ‘Great Tom’. Certainly there is complementary synergy in the exposed Latin inscription and its rhythmic peal; the now lost ‘Bim Bom’ engraving on the bell partially3 matches splendidly with Tom’s seemingly nonsensical verse in The Lord of the Rings. Hooker has also suggested that apart from the bell’s ‘Bom’, Bombadil might have been formulated to sympathetically affiliate with such words as ‘bombio’ to buzz, ‘bombo’ for bass drum – among numerous other offerings.

‘Tom Tower’ housing ‘Great Tom’ – Christ Church College, University of Oxford

Equally puzzling as ‘Tom Bombadil’ is the etymology of ‘Goldberry’. From where, what, or whom did Tolkien elicit that name? Yes – exactly what was the history behind its development? Strangely enough, given its simplicity of construction, convincing answers have been elusive. Nonetheless, as academics would surely universally agree – Tolkien must have had his reasons, and they undoubtedly would have been well-thought-out:

“All4 the names in the book, … are of course constructed, and not at random.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #165 – June 1955, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (my emphasis)

Admirably, Hooker has researched the Welsh language and resulting translations of ‘Gold’ and ‘berry’ as a possible external source (Tolkien and Welsh, 2012). The ‘English calque of a Welsh theonym’ as Hooker suggests is perhaps a little difficult to get one’s head around. Happily for the less academically inclined, I will offer up something much simpler from a rather different viewpoint.

But before embarking on a new quest I must dispense with the obvious. We must acknowledge Tolkien’s direction on foreign translation where he conveyed the name was of compound composition: ‘Gold’ and ‘berry’. That is certainly the most natural interpretation of what the Professor meant by – ‘Translate by sense’:

“Goldberry. Translate by sense.”

– Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien

And this can be easily ascertained from the same being asked of translators in dealing with other two-part fabrications such as Smallburrow, Skinbark, Treebeard, Thistlewool, etc.

Given as much, my own inclination is that ‘Goldberry’ would probably have been named after a particular plant because of the ‘berry’ ending to her name. Most likely it would be an aquatic plant; and if so – one native to Oxford and Berkshire river environs. Because when it came to a range of habitats for Tom (and thus by inference – his partner), it was emphatically related the territorial basis of:

“ ‘… the flora & fauna are meant to be strictly Oxford & Berks’ …”.

– The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide 2006 Edition, Chronology, 8 May 1962, C. Scull & W. Hammond (my emphasis)

Goldberry is of course associated to the Withywindle in the novel which in turn, as some eminent scholars5 have remarked, was almost certainly modeled on Oxford’s River Cherwell. Tom’s singing leaves us a decent clue in hinting that the color ‘gold’ is interchangeable with ‘yellow’:

“Goldberry, Goldberry, merry yellow berry-o!”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, The Old Forest

So perhaps what we should focus on is vegetation that yields yellow berries common to river-lands in two specific English counties.

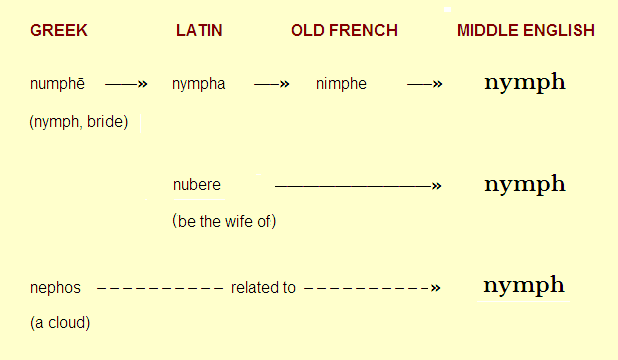

Introducing the Yellow Water-Lily

Leaving speculation aside for the time being, we must acknowledge how Goldberry is firmly linked to water-lilies in the tale. These magnificent plants are of the Nymphæaceæ family, where the Latin based scientific designation (as Tolkien almost certainly knew6) was inspired by Greek nymphs and sirens. Hence, we intriguingly have the water-lily as being linguistically synonymous and intricately bound to the legendary Hellenic ‘water-nymph’.

For Goldberry – the river-daughter, outwardly nymph-like qualities were strongest in early Bombadil poetry where she was depicted as comfortably at home in her water-dwelling, notably among the lilies:

“… up came Goldberry, the River-woman’s daughter;

pulled Tom’s hanging hair. In he went a-wallowing

under the water-lilies, bubbling and a-swallowing.”

– The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, The Oxford Magazine, February 1934

Complementing Greek mythology, later Teutonic and other North European legends possess many examples of mythological merfolk frolicking in fresh waters among lily-pads. Whether with flukes or legs – or whether water-nymphs, sirens, nixies, undines or even mermaids – these sensual aquatic creatures were invariably youthful, beautiful and usually female. Indeed, artistic renditions abound illustrating them in close association to floating river flora across a wide pan of European myth.

Etching from The Journal of Applied Arts and Crafts, Fritz Hegenbart, 1851

‘Nordic Thoughts’ – Siren among the lilies

‘Nordic Thoughts’ – Siren among the lilies

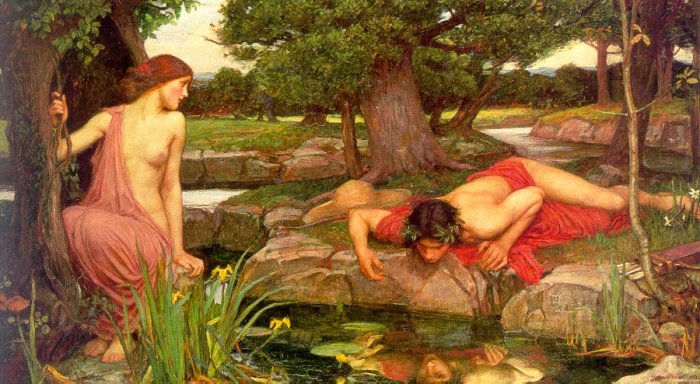

‘Hylas and the Nymphs’7, John William Waterhouse, 1896

Despite taking an active long-term interest in painting and being a gifted artist himself, absolutely no evidence exists that Tolkien ever viewed any of the above artwork. Nonetheless, Waterhouse (and the strong probability of Pre-Raphaelite8 influences) has been mentioned in Michael Drout’s J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment, 2007 (article by James McNelis under Artistic Movements). Since its release, Hylas and the Nymphs has been one of Waterhouse’s more acclaimed portraits. Certainly its mythological nature would have interested any party reared on pan-Hellenic legends.

Though exhibited internationally and twice in London before Tolkien even took up tenure at Oxford, it appears the original never showcased at the Ashmolean Museum9. Nonetheless, due to its fame, if perchance the Professor had run across it – I’m sure with his eye for detail he would have noticed a couple of things about the aquatic flora. Firstly that the nymph-filled pool setting was endowed with both forget-me-nots (lower left corner) and yellow flag-lilies (upper right corner). But perhaps more importantly – present were two different color water-lilies10.

Zoom in on Yellow & White Water-lilies, ‘Hylas and the Nymphs’

Getting back to specific flora indigenous to Oxfordshire waters – though the Cherwell’s most famous lilies are white (as were those Tom brought Goldberry) the river also happens to seed a more profuse yellow variety.

‘The History of Banbury’ – extract from pg. 575, Alfred Beesley, 1841

Notably alba and lutea are feminine forms of the Latin words for ‘white’ and ‘yellow’ respectively. Given that masculine equivalents exist, not unreasonably it can be concluded that these plants spawned from life-giving waters are effectively ‘daughters of the river’11.

William Baxter’s ‘British Phænogamous Botany’, Oxford, 1839

Nuphar lutea, Yellow Water-lily

Unquestionably Tolkien knew of the yellow water-lily’s existence. It is mentioned in the Appendix (pg. 248) to The Book of Lost Tales I as ‘nénu’ in early Elvish. In all likelihood the derivation was sourced, in early adulthood, from the lily’s Medieval Latin name: Nenuphar12 – which, of course, had subsequently led to the scientific Nuphar contraction. In taxonomic descriptions this plant is commonly titled the ‘Brandy Bottle’13 due to the flask shape of its spent fruit. The flower itself smells like a fermented alcohol – and so the ‘dregs of wine’ is an often employed traditional English phrase both capturing and conveying its slightly noxious aroma.

‘Brandy Bottle’ – Yellow Water-lily Fruit

A subtle and deliberate interconnection of Nuphar lutea with the Withywindle tributary and then further to the naming of the Brandywine14 River by Tolkien should not be downplayed. Not every relationship or connotation within the story ended up being expanded upon. Nor was everything fully explained in the book’s appendices15.

Look Again and Reimagine the Familiar!

At this point, with an intoxicating alcoholic whiff in the air, we need to return to The Fellowship of the Ring text. At our first encounter with Goldberry, I suggest we read her description, close our eyes and then attempt to pensively visualize unconventionally. We should try and think in terms of the imagery put out by Tolkien.

Perhaps we should try employing the ‘Mooreeffoc’ principle16, for fantasy creation, Tolkien identified in On Fairy-stories and strive to see what might have become banal from a new perspective. And so if we focus on that alluring introductory paragraph, a metaphorical portrait of something other than a woman might mentally form:

“… yellow hair rippled down her shoulders; her gown was green, green as young reeds, shot with silver like beads of dew; … About her feet … white water-lilies were floating, …”.

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

In Goldberry’s initial posture what the Professor predominantly depicted was a mass of wavy yellow hair shouldered atop a glistening green gown raised above what seemed like a watery bed of buoyant white lilies:

“… so that she seemed to be enthroned in the midst of a pool.”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

Her limbs were not mentioned, nor the color of her eyes, nor any part of her face at this initial description. All of this is so much in contrast to Tom, whom Tolkien happily described at outset as possessing: “thick legs”, “eyes” that “were blue”, and a “face … red as a ripe apple, … creased into a hundred wrinkles”. Yes, we have a curious divergence for Goldberry from past practice.

So if we think thoughtfully and work with scenic imagery of a natural pool Tolkien himself provided us – our slender-figured hostess, I deem, epitomized the very essence of a water-lily. No – not one of the white variety. But instead, a fully bloomed yellow lily – whose wavy-petaled head sat atop a single green water-spattered17 stalk risen well above the water with roots (represented by her feet) anchored below its surface. By leaving out (in that opening narrative) facial features, skin color and any mention of limbs – Tolkien left us articulate worded artistry emblematic of a special flower. The gold belt, chair and her lofty position seem to figuratively signify that she was indeed an “enthroned … queen” of all Withywindle water-lilies, who had once reigned supreme in her shady pool. Such a motif can be reasonably perceived for our fair Goldberry. Of course with some lateral imagination!

Coincidentally (perhaps), a parallel exists of Goldberry’s indoor pose in another Waterhouse painting. This time in an outdoor portrayal – a young, fair-skinned and beautiful woman18 is similarly depicted as seated above an expanse of white water-lilies and their accompanying leaves. Remarkably the woman possesses a silver dress and ‘bejeweled gold’ belt just like Tom’s pretty lady!

‘Ophelia’19, John William Waterhouse, 1894

Anyhow, returning to the book – quite possibly Tolkien enhanced the first encounter’s visual imagery by audible means in the construed departure from the center of the ‘indoor pond’. To greet her guests, for they were on ‘land’, Goldberry had to metaphorically first pass the water’s edge:

“… her gown rustled softly like the wind in the flowering borders of a river.”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

Beyond that initial contact, perceptible is even more subtle artistry lying behind features of the guest sleeping quarters. The ‘penthouse’ interior:

“… walls … were mostly covered with green hanging mats and yellow curtains. The floor was … strewn with fresh green rushes. There were four deep mattresses, each piled with white blankets, …”.

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil (my emphasis)

Hmm … green mats profusely bedecking the walls furnished a verdant backdrop for yellow curtains covering the east and west facing windows. While green rushes spread upon the floor surrounded four individual mattresses over which white blankets were to be spread. A lot of yellow, green and white we can readily conclude. What’s more, colors that perfectly match both types of English water-lily.

So what effect, we ought to consider, results from the drawn curtains gently swaying now and again against the greenery?

“A little breath of sweet air moved the curtain.”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

And then what about re-visualizing the mattresses covered in white blankets ruffled by the tucked-in hobbits?

Maybe we need to let our imaginations run wild! Perhaps some of us will have to try quite hard – but wasn’t the decor and atmosphere symbolically reminiscent of yet another natural water-scene? One set at nighttime? Might not one picture four closed up white lilies floating atop a rushy margin20 of a river with two of the yellow variety gently billowing close by!

Hmm … it appears mundane detail belied a sophisticated purpose. One so deftly executed it has seemingly escaped us all. Part of Goldberry’s lodging was aesthetically fashioned to be a home away from home!

Extract from ‘Convent Thoughts’, Charles Allston, c. 1850 – Exhibited at The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Am I done exploring river-setting imagery in Tom’s house? Not quite. Because now we can see how Merry’s dream fits in. While asleep upon his ‘water-lily bed’ he imagines he is effectively slowly sinking:

“It was the sound of water that Merry heard falling into his quiet sleep: water streaming down gently, and then spreading, spreading irresistibly all round … into a dark shoreless pool. It … was rising slowly but surely. ‘I shall be drowned!’ he thought.”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

Just maybe Tolkien based the gradual submergence scene21 on a phenomenon exhibited by white water-lilies as outlined in a prized botany book. Known as phototrophs – being stimulated by light (or its absence):

“The flowers rise above the water in the middle of the day and expand, closing once more and sinking towards evening.”

– Flowers of the Field, Nymphæáceæ – Water-Lily Family – pg. 24, C.A. Johns, 33rd Edition, 1911 (my emphasis)

Hmm … to briefly summarize then: all in all some fairly beckoning revelations lie exposed before us. It’s tempting to conclude the Professor’s ability to:

“… visualize with great clarity … detail scenery and ‘natural’ objects, …”,

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #211 – 14 October 1958, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (Tolkien’s emphasis)

was carefully channeled into creating meaningful imagery. Principally river-vegetation imagery requiring interpretation from an ‘artistic’ angle before the reader could absorb and appreciate the true depth behind these vistas.

And so given all the peculiar linkage to Nature observed so far – we are left with little choice but to probe deeper. At this point it is worth scrutinizing the plant genus, and particularly the yellow species, in more detail. Especially when Tolkien’s ‘most treasured book’ (see footnote 12) in sub-categorizing this variety under Nymphǽa – passes the following remark:

“Yellow Water-lily … Named from its growing in places which the nymphs were supposed to haunt.”

– Flowers of the Field, Nymphæáceæ – Water-Lily Family – pg. 23, C.A. Johns, 33rd Edition, 1911

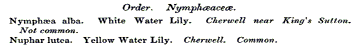

The Yellow Water-lily and the Yellow Berry

One interesting matter resulting from word origin research, is that the Nymph in Nymphæaceæ or Nymphǽa has a dual meaning. Its Latin etymological source: nympha, also means ‘bride’.

How curious! One can’t help but suspect that Tolkien as a professional philologist knew of this duality. After all, both aspects of nympha are reflected in the 1934 The Adventures of Tom Bombadil poem. For after flirtatious water-capering, the cavorting culminated in a wedding with Goldberry becoming Tom’s spouse:

“Old Tom Bombadil had a merry wedding, …”.

– The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, The Oxford Magazine, February 1934

Also noteworthy, is how the Greek equivalent of nympha is numphē and that a related nubere in Latin means: ‘take a husband’. Maybe then for a mix of Greek mythology with Greco-Latin etymology, that is stretchable to ‘nymph – take a husband’. In that light, if the constituent bere22 can be extrapolated to ‘berry’, the latter half to ‘Goldberry’ appears highly befitting. Hmm – one can only wonder if Tolkien thought along such lines!

Etymology* of the mythological ‘Nymph’

* Largely per Chambers Etymological Dictionary of the English Language, 1896. Tolkien owned the 1903 issue.

Encouraged by some etymological progress, we must remind ourselves that it is our most ancient records of what is now the British Isles and continental Europe that most strongly connect to Tolkien’s mythology. Though we have the beginnings of an ‘external’ linkage of our world to his feigned Third Age, what about the ‘internal’ connection? What might have been the derivation of ‘Goldberry’ internal to the tale?

For that, I have a straightforward possibility. Namely that ‘Goldberry’ was simply a Common Speech corruption of the Sindarin: ‘Golodh bereth’23 – glossed as ‘Elvish Queen’ or ‘Wise Elf Queen’. This two-word combination, once merged, is a plausible phonetic match and furthermore fittingly ties in with Frodo’s first impression of being:

“… answered by a fair young elf-queen24 …”.

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

It is quite probable that the elves knew of Goldberry’s existence before the locally settled hobbits. Whether the corrupted rendering25 was Bucklandish in origin – I cannot prove. Nonetheless, one can easily imagine the scenario where the Buckland hobbits were the first among their kind to gain knowledge of her – and that through the fair-folk. Imaginably becoming ‘worn down’ over time, an initially relayed Sindarin name-form underwent gradual pronunciation distortion into more palatable Shire-speech!

External to the tale, there might have been more than just etymological roots to the characterization of ‘Goldberry’. To establish whether this was the case, we need to once again look at our beguiling floral candidate – but from a seasonal standpoint. Coming full circle from my suggestion near the beginning of this article, we should seek river-land vegetation that produces yellow ‘berries’. Or imaginatively – near enough!

And so if we scrutinize a queerly appealing perennial plant – there is most definitely one remarkable feature to the yellow water-lily’s life cycle. In Oxfordshire in late spring and early summer is when it begins budding. At this point it strongly resembles a berry. Yes a yellow berry; conceivably one might even say: a gold berry!

Yellow Water-lily Buds

Deep-rooted Connections to Water-lilies

Goldberry being “young”, vibrant and vernal-voiced makes for close association to both early seasons when each yellow lily ‘berry’, in slow-flowing English waters, takes shape atop a single stem. It is at this point we should recall that the word ‘nymph’ traditionally has connotations relaying ‘youth and budding beauty’. Despite such a word being used in science to entomologically describe an intermediate pre-adult stage of certain insects, it is not wholly inappropriate to think of it in terms of the initial stage of a flower’s development. More so because the bud too undergoes a kind of metamorphosis.

Now though full flowering may continue beyond September – the yellow water-lily’s budding season is basically over by summer’s end to renew in the following spring. This slots in comfortably with Frodo’s26 rhyme:

“… Fair River-daughter!

O spring-time and summer-time, and spring again after!”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

By late autumn the flower, leaves and stem die away leaving just the root rhizome. It is likely that Tolkien – who had a marked penchant to flora, having accumulated considerable botanical knowledge27, would have known these details. A glimpse of such passion shines through in one of Warren Lewis’s diary entries where he recorded Tolkien:

“… with his botanical and entomological interests28, …”

– J.R.R. Tolkien: The Making of a Legend, The Struggle to Publish – pg. 203, C. Duriez, 2012

would take time to observe the countryside’s natural beauty during long strolling walks in the Malvern Hills. Again in that same vein:

“All illustrated botany books … have for me a special fascination.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #312 – 16 November 1969, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

Where exactly Tolkien first encountered water-lilies can be astutely guessed from his brother Hilary’s account of childhood adventures at Sarehole, a hamlet in Warwickshire29:

“In very far off days in a part of Warwickshire, there dwelt a Black Ogre and a White Ogre. The one had wonderful flowers growing along the banks of the stream … Sometimes you had to paddle in order to get the water blobs, …”.

– Black & White Ogre Country, Bumble Dell – pg. 2, A. Gardner, 2009 (my emphasis)

Hilary, of course, employed a regional colloquialism:

“BLOB. Water-blobs are water-lilies30”.

– A Dictionary of Archaic and Provincial Words, pg. 187, J.O. Halliwell-Phillipps, 1901

And it would be a touch incredulous to accredit Ronald as having been less interested in plant-life than his sibling. Especially given an inbuilt desire for:

“… contact direct with an unfamiliar flora …”.

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #312 – 16 November 1969, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

Most pertinently Tolkien told us:

“ ‘I lived till I was 8 at Sarehole …’ ”.

– The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide 2006 Edition, Chronology, 1896–1900, C. Scull & W. Hammond

Leaving us certain that this rustic settlement is where the botanical side of his scientific knowledge began its advance:

“ … at seven … I was interested … in the structure and particularly in the classification of plants31; …”.

– Tolkien On Fairy-stories, Manuscript B MS. 4 F. 73-120 – pg. 248, V. Flieger & D. Anderson, 2014 (my emphasis)

With his mother, Mabel, being at the forefront, she was no doubt the intended recipient of those fresh specimen ‘water-blobs’ for joint examination:

“His mother taught him a great deal of botany, and he responded to this and soon became very knowledgeable.”

– Tolkien: A biography, Birmingham – pg. 22, H. Carpenter, 1977

Now when it came to residing in Oxfordshire, the Professor ought to have regularly espied the county’s more common yellow water-lily heads poking through the Cherwell’s surface. Over many years at Oxford, the seasons for emergence of stems and flowering (and those in which they were absent) should have been readily apparent in equally lazy brown waters as those of the Withywindle.

During their budding phase these bright points of color would have been hard to miss – especially on July and August afternoons while on the drably hued Cherwell:

“… floating in the family punt hired for the season32 …”.

– Tolkien: A biography, Northmoor Road – pg. 160, H. Carpenter, 1977

It doesn’t take much to visualize top-heavy flexible stems swaying in the breeze or ripples resulting from the boat’s passage. One can understand why above water – the plant might appear to ‘dance’; aptly, I suggest, giving the ‘merry’ to:

“Goldberry, Goldberry, merry yellow berry-o!”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, The Old Forest (my emphasis)

Yellow Water-lily pads atop the River Cherwell at Sparsey Bridge*

* To the west is Water Eaton (see footnote 30). To the east is Woodeaton (also known as Wood Eaton). Along these banks was a favorite picnic spot.

And so this is perhaps an opportune moment to recall the importance of personal experiences. For ‘external sources’ Tolkien stipulated that:

“… it is the particular use in a particular situation of any motive, whether invented, deliberately borrowed, or unconsciously remembered that is the most interesting thing to consider.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #337 – 25 May 1972, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

Throughout his semi-rural Midlands upbringing (in those self-admitted most formative years) – interaction with Nature was commonplace. Even when located in Oxford the glorious English countryside was just a stone’s throw away. He freely admitted:

“I take my models like anyone else – from such ‘life’ as I know.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #181 ~January 1956, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (Tolkien’s emphasis)

Handily for The Lord of the Rings, some of Tolkien’s inspiration literally lay just outside his doorstep. The Rivers Isis and Cherwell running through the heart of Oxford had a special bond with its history and connection to water-lilies. William Turner, a renowned local artist, had painted two nationally lauded portraits of lilies gracing the Cherwell.

‘Waterlilies in the Cherwell’ by William Turner (of Oxford), c. 1850’s

At the University of Oxford, we know there were water-lilies in his own Exeter College grounds. According to Warren Lewis the Fellows’ Garden ended:

“… in a little paved court with a sunk pond where a small fountain plays on water lilies: ...”.

– Brothers and Friends: The Diaries of Major Warren Hamilton Lewis, 1933 – pg. 105, C. Kilby, 1982

They naturally flourished in other areas of the university grounds too:

“… in the water walk called Mesopotamia, the summer visitor will see beds of water lilies, ...”.

– Historic Towns Oxford, Modern Oxford – pg. 214, C. Boase, 1893

Right next to Magdalen College and its campus, where C.S. Lewis had taught and resided, is the famed Lily House. Part of the oldest botanical garden in England, it is one of the few which grow the giant Amazonian Victoria Cruziana lily.

‘Victoria Cruziana Water-lily’, Lily House, University of Oxford Botanical Gardens

But perhaps most appropriately, Tolkien might have felt, was their seasonal presence in the fountain within ‘Tom Quad’. Sited adjacent to ‘Tom Tower’, Christ Church College’s sunken fountain has long33 been associated with a fleet-footed god34; certainly well before Tolkien’s arrival in Oxford as an undergraduate.

Water-lilies in ‘The Mercury Fountain’ – Tom Quadrangle,

Christ Church College, University of Oxford

One can see then – how opportunities abounded for pre-novel contact with this family of aquatic flora. And Tolkien readily confessed:

“I am (obviously) much in love with plants …”.

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #165 – 30 June 1955, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

Then at the risk of sounding cliché, if we neglect the depth to which plant-based knowledge was embedded in his opus – it is at our own peril:

“There’s nothing in ‘The Lord of the Rings’ except that it’s a foundation of one’s feelings for trees, flowers and England generally.”

– Niekas interview (see Tolkien Studies 15, pg. 163), late spring 1967 (my emphasis)

The Symbolic Importance of a Special Flower

Now in addition to the city’s history, we know Oxford’s rivers played a role in family ‘adventures’35. Besides the danger of tripping over exposed willow-roots, snare-like tendrilled lily-beds would have presented tricky obstacles to navigate past. Family man Tolkien certainly was, and the craft was steered by skillful hands. For all seasoned punters knew extra care had to be taken when confronted by the lurking hazards36 concealed by the Isis and Cherwell. In a way Tom was family-oriented too. And if my hunch is correct Goldberry was no different.

Unless further factual information comes to light, we can only guess the truth behind why Tolkien had Tom gather white water-lilies for Goldberry. At first sight the given reason is plain enough:

“… to please my pretty lady, …”.

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

‘Gathering Water-Lilies’, East Anglia, 1886 – A traditional English activity

Nevertheless, the real motive might have been more subtle. Goldberry, as ‘queen of all lilies’ – I surmise, was not just monarchical but also had a semi-symbiotic relationship with her ‘subjects’ (and no doubt ‘friends’): the water-lilies. The health of various river domains ought to have been much dependent on them. Aeration of the waters and the provision of a unique sub-ecosystem by the leaves was of vital importance. Though one can deduce Frodo sang of Goldberry’s bubbly breath37 being responsible for:

“ ‘… the leaves’ laughter!’ ”,

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

Tolkien’s botanical expertise probably extended to knowing that with the water-lily:

“Oxygen gas is copiously evolved in bubbles from its leaves.”

– British Phænogamous Botany, Nymphǽa, William Baxter, 1837

Intermittent escape (instigating motion) imaginatively giving the impression of the leaves’ laughing!

In any case – given a welfare concern, it is suggested that Goldberry was just protecting the eldest and most vulnerable from inclement weather: impending storms and winter frosts – something which she did annually. White lilies were her focus simply because they are the less hardy of the two though their blooms last slightly longer into the season; and yes indeed they can survive and even thrive in containers38:

“… in wide vessels of … earthenware, white water-lilies were floating, …”.

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

Tom’s task was clearly urgent:

“ ‘… Tom had an errand there, that he dared not hinder.’ ”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

Moreover, gathering water-lilies (leaves and all39) was a rare event; it had nothing to do with house beautification:

“Each year at summer’s end I go to find them …”.

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

So it seems Tom’s bride had not completely forsaken her special pool. Consequently, the ritual of bathing in it at spring-time was perhaps to welcome her new subjects – the fresh buds of emergent water-lilies, both white and yellow. Far from abandoning the river’s special inhabitants – she was there to help the aged and nurture the very young!

Of course the above is conjecture. Nevertheless, the connection of Goldberry to a flower is impressed upon us not only at our first meeting, but also our last. There at farewell, once again Tolkien left us with a similar vision of a yellow-headed lily. One which stood proudly over an expansive yet semi-submerged green leaf. Or perhaps even protruding from a green pool like that in Once Upon a Time40:

“ ‘Goldberry!’ … ‘My fair lady, clad all in silver green! …’ … her hair was flying loose, and as it caught the sun it shone and shimmered. A light like the glint of water on dewy grass flashed from under her feet …”.

– The Fellowship of the Ring, Fog on the Barrow-downs

And at last sight, with Tolkien’s self-specified sun imagery in mind, what flower could look more lit up than the near-globular petal-cluster of a yellow water-lily?

“… they saw Goldberry, now small and slender like a sunlit flower against the sky: …”.

– The Fellowship of the Ring, Fog on the Barrow-downs (my emphasis)

Surely then – we should acknowledge scientific designations pertaining to the fruit? How can we ignore the flower’s ‘yellowy-gold’ heart being termed a ‘berry’?

“berry many-celled” – Flowers of the Field, C.A. Johns, 1853

“Berry of many cells” – English Botany, Vol. III, J. Sowerby, 1794

“berry superior” – Pantologia, Vol. 8, Good/Gregory/Bosworth, 1813

Or from its head – many curly filaments conveying imagery of yellow rippling hair. And how by autumn that ‘hair’ would look ‘long’ with the added blending-in of petals opening out to their fullest.

When Tolkien stated that:

“Goldberry represents the actual seasonal changes …” in “… real river-lands …”,

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #210 – June 1958, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

one can readily conclude that more than anything else – she symbolized the changes experienced by a flower: the yellow water-lily, another nymphean “daughter of the River”. This native Oxfordshire plant, when budding in spring and summer, I believe – is the ‘external’ and true inspirational source of the name: ‘Goldberry’!

For the next article in the series click below

Part II

Footnotes:

1 Poem published in the 15 February 1934 edition of The Oxford Magazine (Vol. 52, No. 13 pgs. 464-465).

2 Michael Tolkien’s Dutch doll. Pre 1934, there is no record of any of Tolkien’s children possessing toys with names assigned from his body of Silmarillion myths.

3 The ‘Bom’ arises per:

“Tom Bom, jolly Tom, Tom Bombadillo!”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, The Old Forest

The ‘Bim’ is missing from the text.

4 Tolkien’s statement is inclusive of the name ‘Goldberry’, despite this character first arising in The Adventures of Tom Bombadil poetry of 1934 which preceded commencement on what became The Lord of the Rings.

Given how his mindset was such that:

” ‘… Names always generate a story in my mind. …’ ”,

– Tolkien: A biography, The storyteller – pg. 172, H. Carpenter, 1977

one can reasonably deduce that Goldberry must have had a story behind her at the point of poetic creation. Thus, it is highly likely a ‘real world’ exterior factor prompted Tolkien’s naming choice, regardless of her having no known preexisting foothold in his fictitious world.

5 Tom Shippey (The Road to Middle-earth, A Cartographic Plot – pg. 108) and Christina Scull/Wayne Hammond (The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide 2006 Edition, Reader’s Guide, Nature – pg. 632) identify the Cherwell with the Withywindle.

Backing up a prognosis of the Oxford river being assimilated into hobbit territory (or that very close by) is evidence which can be gleaned from early draft material. We must note Wood Eaton is an Oxfordshire village lying close to the Cherwell, and that correspondingly in an early draft (see The Return of the Shadow, A Long-Expected Party – pgs. 29 & 35) Wood Eaton was the name of a village located adjacent to the Brandywine River into which, it was later decided, the Withywindle flowed.

To Tolkien, Wood Eaton would have felt appropriate because it is based of Anglo-Saxon etymology – ‘Eaton’ being ‘a town next to water’. So Wood Eaton is literally a town sandwiched between water and a wood; very befitting of a habitation between the Brandywine and the Old Forest. Ultimately though, the Anglo-Saxon linkage was rejected.

6 Because of:

(i) A passionate interest in English flora (see footnote 12),

(ii) His occupation as a professional philologist,

(iii) A thorough education in the Classics (Greek and Latin) – “I have, for instance, a particular love for the Latin language, …”, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #294 – 8 February 1967, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981.

(iv) A lexicographic study of ‘water’ while employed at the NED (see Tolkien: A biography, Oxford interlude, 1977 – pg. 101, by Humphrey Carpenter). Such research almost certainly resulted in investigating its British English hyphenated compounds (i.e. water-lily, water-nymph etc.).

7 The tale of Hylas is worth briefly repeating here, for it tells of the Greek mythology behind the yellow water-lily. The summary below is disseminated from Flower Lore and Legend, The Water Lily, 1917 by Katharine Beals.

After landing on an island in the expedition of the Argonauts to wrest away the Golden Fleece, the youth Hylas – beloved of Hercules – becomes separated. The nymph Lotus, once spurned by Hercules, had been transformed out of pity by the goddess Hebe into a white water-lily. Lotus takes revenge by having her naiads (water nymphs of a spring, river or waterfall) lure Hylas into their pool of lilies where he is pulled in and held fast. The entirely white lilies of the naiads subsequently become tinted gold – the identifying color of the Argonauts – giving rise to the mythical origin of the yellow water-lily.

In 1910 the English artist Henrietta Rae produced Hylas and the Water Nymphs in a setting and style reminiscent of Waterhouse’s. Again the yellow water-lily is a feature.

8 One of the early members of the Pre-Raphaelites (a group of visual and literary artists) was William Morris (a fellow Exeter College graduate) whose prose, poetry and pattern designs Tolkien became greatly familiar with. Tolkien bought Morris’ The Life and Death of Jason, 1867 with his Walter Skeat Prize money in 1914. Within Book IV (titled The quest begun – The loss of Hylas and Hercules) the fate of Hylas is versified in quite some detail. Thus, it is highly unlikely Tolkien was unaware of Hylas or his hapless encounter with the alluring water-nymphs. Moreover, the tale appears in the works of past masters Theocritus, Ovid and Apollonius – whose teachings made up part of Tolkien’s school and undergraduate curricula. Theocritus’ version is retold in Cecil Bowra’s The Oxford Book of Greek Verse in Translation, 1938 whose introduction Tolkien assisted in per The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide 2017 Edition, Chronology, January 1938 by Christina Scull & Wayne Hammond.

We also know Tolkien attended a presentation (perhaps more) in 1913 on Dante Rossetti, a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood:

“Three meetings of the Exeter College Essay Club are held in Hilary Term, at which papers are presented on … the poetry of Oscar Wilde, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti as a poet and artist.”

– The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide 2006 Edition, Chronology, Hilary Term 1913, C. Scull & W. Hammond (my emphasis)

We can see how significant the inclusion of flora was to this member from his own comment about the painted in ‘ivy’ in Proserpine – though, of course, it isn’t known whether this particular work was part of the articulated or visual material:

“The ivy branch in the background may be taken as a symbol of clinging memory.”

– Wikipedia article: ‘Proserpine (Rossetti Painting)’

‘Proserpine’, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1874

Later in life Tolkien explicitly mentioned the Pre-Raphaelite style of vivid color usage in Letter #333 – 16 March 1972 (from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981). Impressed upon him in undergraduate years must have been colorful murals in the Oxford Union Library painted by William Morris, Dante Rossetti and other fellow artists in the movement. These he could hardly have missed (least – two of Sir Gawain). Nor those housed in his own Exeter College (e.g. The Adoration of the Magi by Edward Burne-Jones). However, Tolkien’s acquaintance with the Pre-Raphaelites stemmed from pre-university days. Humphrey Carpenter has presented evidence in Tolkien: A biography, War, 1977 – pg. 73 that a private school club, the T.C.B.S., was modeled with similar aspirations in mind to those of the Brotherhood – at least from Tolkien’s view.

9 The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford does hold an early partial sketch of Hylas and the Nymphs (see below). The fully finished painting itself is housed in the Manchester Art Gallery.

When first appraised in 1897, a critic from The Times newspaper complained that the nymphs shared an almost identical look. I suspect this was deliberate on Waterhouse’s part. Greek mythology certainly relates nymph to water-lily transformation. For this species of flowering water-flora – each headed petal-cluster looks much the same when an individual bed is in multiple bloom. The variation in flower to flower is usually quite minor. Speculatively then, naiads of a single pool stemming from a reverse metamorphosis might be imagined to look sisterly and thus very similar to each other.

10 Indeed, the yellow water-lily is hard to miss – simply because the largest occupies an almost perfectly central position in the full portrait. Akin positioning also occurs in Waterhouse’s 1903 nymph-featured oil – Echo and Narcissus (this time, lower-center).

Connectivity of these minor water-goddesses to yellow water-lilies, and its deeper significance, was seemingly not lost on this particular artist. One can reasonably conclude Waterhouse was suitably versed in the botanical aspects of the mythology lying behind those femmes fatales.

11 A probable Tolkien devised kenning in Old English style based upon Goldberry’s textual titling of ‘river-daughter’. Such a prognosis will become much stronger after suitably digesting discussion of our world’s water-lily metamorphosis myths in Part II.

12 Also the French name for a water-lily.

The yellow water-lily’s medieval Latin name: Nenuphar bears phonetic similarity to Tolkien’s ‘nénuvar’ – defined as a ‘pool of lilies’ (The Book of Lost Tales I, Appendix – pg. 248). Again, this suggests Tolkien actively explored the etymology of this river-plant.

In the English language instances exist where ‘v’ and ‘ph’ are interchangeable yet have the same meaning. Stephen/Steven and phial/vial are two examples. Tolkien’s preferences for an older form of etymology using ‘v’ instead of ‘f’ (e.g. dwarves vs. dwarfs) is well documented. Whether he felt the same applied for ‘v’ and ‘ph’ is unknown, but quite possible – especially as the ‘ph’ in Nenuphar is pronounced as if it were ‘f’.

13 Per Flowers of the Field, 1911 (pg. 23) by Charles Alexander Johns (reported in Tolkien and The Silmarillion by Clyde Kilby as Tolkien’s “most treasured book” – see Chapter II – Summer with Tolkien, pg. 26):

“Nymphǽa (Yellow Water Lily).

1. N. lútea (Common Yellow Water-lily, Brandy-bottle). …

Flower smelling like brandy, whence it is called Brandy-bottle.” (my emphasis)

This book is recorded as the one which most influenced Tolkien as a teenager (The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide 2017 Edition, Chronology, 25 December 1971 by Christina Scull & Wayne Hammond).

14 An apt example of how Tolkien used a river, water-flora and ancient language, in combination, to connect his imaginary epoch to our world is laid out in one of his letters:

“… the … Gladden River, … which contains A.S. glædene ‘iris’, in my book supposed to refer to the ‘yellow flag’ growing in streams and marshes: sc. iris pseudacorus … not iris foetidissima to which in mod. E. the name gladdon (sic) is usually given, at any rate by botanists.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #297 – August 1967, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (A.S. an abbreviation of ‘Anglo-Saxon’, sc. an abbreviation of ‘scientific’, my underlining)

Given such a thought train – one can apply parallel thinking to our particular species and the Withywindle tributary flowing into:

“… the … Brandywine River, … which contains A.S. used Lat. nimphea ‘lily’, in my book supposed to refer to the ‘yellow water-lily’ growing in streams and marshes: sc. nuphar lutea … to which in mod. E. the name brandy-bottle (sic) is usually given, at any rate by botanists.”

Perhaps Tolkien would have provided such an explanation – if asked!

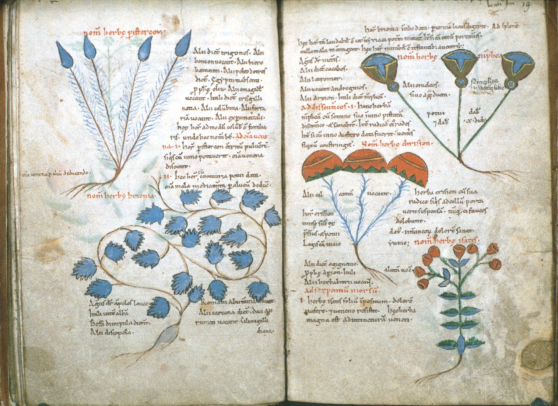

Nimphea* (Water-lily) RHS, ‘Pseudo-Apuleius Herbarium’** (late 11th century)

* Latin Name=Nimphea, Anglo-Saxon=Eadocca, from Archbishop Alfric’s Vocabulary (pg. 136) in Anglo-Saxon and Old English Vocabularies, Volume 1, 1884 by Thomas Wright.

** It has been remarked that Tolkien was very likely acquainted with this manuscript – see Michael Drout’s J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment – Leechbook and Herbarium (pg. 350).

15 A discussion of the name ‘Brandywine’ is provided in Appendix F of The Lord of the Rings but is restricted to an in-mythology hobbit perspective. Even then – an alcoholic link (“heady ale”) is evident; though frankly, Tolkien provided an unconvincing association.

It is quite apparent that the name ‘Brandywine’ was in Tolkien’s plan from near inception of the ‘new’ tale (see The Return of The Shadow – The First Phase, Chapter I). And that is because, as I have suggested, of a desired philological ‘exterior’ link to water flora – i.e. the name being derived from common English appropriations for the yellow water-lily. One might deduce that Tolkien’s logic centered on the aroma and oozings from separated yellow water-lily fruit, having floated down beyond the Withywindle, wafting and seeping their way into the more inhabited regions of the greater river – thus giving rise to its naming by local hobbits. However later on (past the point of amendment), Tolkien regretted that no reasonable ‘interior’ link had been provided to the distilling of brandy and Hobbits (see The Peoples of Middle-earth, The Appendix on Languages, pg. 72).

One can understand why the suitability of the stem ‘Brandy’ for Common Speech naming was deemed questionable by the Professor. After all, as a product, it is distinctly connected to the French with its traceable etymology originating with the Dutch. Both aspects are manifestly un-English.

16 Sourced from Charles Dickens and picked up by G.K. Chesterton, Tolkien approved of this “wholesome” form of fantasy:

“Mooreeffoc is a fantastic word. … It is Coffee-room, viewed from the inside through a glass door, … it was used by Chesterton to denote the queerness of things that have become trite, when they are seen suddenly from a new angle.”

– The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, On Fairy-stories – pg. 146, HarperCollins, 1983

17 Among botanists the yellow water-lily is commonly termed ‘spatterdock’ for reasons that remain murky. The ending ‘dock’* is also employed in the names of several other broad-leafed English plants, and probably stems from Anglo-Saxon ‘docca’. For instance, the Anglo-Saxon name for the water-lily is ‘eadocca’ – literally the ‘water dock’.

Tolkien doesn’t specify the species of lily in The Adventures of Tom Bombadil poem, although he does tell us the season is summer. It is quite possible Tolkien envisaged the yellow variety as present by the ‘waterside’ with its white relation. In English waterways both the yellow and white kind often coexist in close proximity:

“Equally frequent and generally in company with the white water-nymph, we find its yellow Naiad sister, Nuphar lutea, …”.

– The Illustrated London Almanack, Volume 6, White and Yellow Water-lilies – pg. 56, 1867

Yellow and White Water-lilies coexisting in Nature, Norfolk Broads – England

With Tom wallowing in the water, as Goldberry pulled him under, and no doubt droplets flying in the air, one can imagine the floating leaves, stems and flowers of nearby yellow water-lilies becoming spattered with water. If one had asked Tolkien – perhaps he would given a mythological incident as the source of the nickname ‘spatterdock’!

* Tolkien appears knowledgeable on this matter as he comments on “plants with big broad leaves, e.g. burdock” in Letter #93, 24 December 1944 (from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981).

18 The woman is Ophelia from William Shakespeare’s Hamlet. In Waterhouse’s painting she is actually depicted sitting on a willow branch. In the play, the branch breaks (the tree proves treacherous) and Ophelia falls to her death.

19 Of course Tolkien was familiar with Shakespeare’s Hamlet – as well as the character Ophelia:

“… Hamlet; … came out as a very exciting play. … to my surprise the part that came out as the most moving, … was … the scene of mad Ophelia singing her snatches.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #76 – 28 July 1944, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

Though not directed at Goldberry, of note is Tom Shippey’s comment*:

“… ‘rootedness’ comes from having deep roots in old and half- or more than half-forgotten myth, as Tolkien thought was the case with … Beowulf and Shakespeare’s … Hamlet, …”.

– Roots and Branches, Tolkien and the Appeal of the Pagan: Edda and Kalevala – pg. 31, Essay by T.A. Shippey, 2007 (my emphasis)

* Observation comes from remarks made by Tolkien in his 1953 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight essay (second paragraph).

20 Even the long bench at the far side of the room surrounded by an atmosphere of misty steam – can conceivably be imagined as a fog-shrouded riverbank from afar. Especially since earlier, while in the Old Forest, we are told:

“White mists began to rise and curl on the surface of the river and stray … upon its borders. Out of the very ground … steam arose …”.

– The Fellowship of the Ring, The Old Forest

Nor should we forget that Tolkien declined to give the hobbits conventional beds. Mattresses purposely lain on the flagstone floor meant direct surface contact of ‘lilies to water’, thus giving the projected imagery more realism.

Given the small size of Tom’s house, one would assume the four mattresses (positioned against one side wall of the penthouse) were purposely designed for hobbit guests. The reader is free to picture their shapes as Tolkien never specified them. Given hobbit preferences for round architecture (windows, doors, tunnels), one might wonder whether that translated across to some furniture – in particular: beds. Round mattresses would nicely add to the artistry.

21 The scene and phenomenon is manifested in Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem Now Sleeps the Crimson Petal:

“Now folds the lily all her sweetness up, And slips into the bosom of the lake.”,

and Thomas Moore’s Paradise and the Peri:

“Those virgin lilies, all the night

Bathing their beauties in the lake.

That they may rise more fresh and bright,

When their beloved Sun’s awake.”

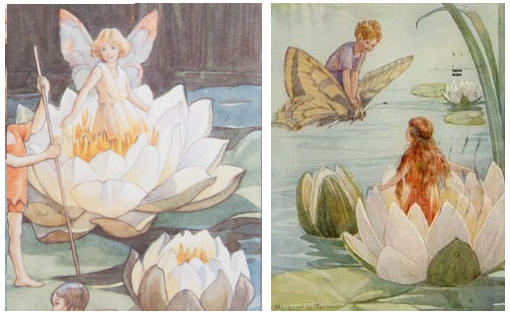

We must note illustrations of little mythical creatures atop white water-lilies crop-up in several fairy tale books.

Extracts from ‘Thumbelina’ (Hans Andersen) & ‘In Fairyland’ (Richard Doyle)

‘Joan in Flowerland’, illustrated by Margaret Tarrant, 1935

22 ‘Bere’ in Middle Dutch and Old High German is the word for ‘Berry’. In Middle English it is ‘Berye’; in Old English ‘beriġe’.

23 From Tolkien’s own notes we have:

“Golodh was the S equivalent of Q Ñoldo …”,

– The War of The Jewels, Quendi and Eldar – pg. 364, 1994 (‘S’ & ‘Q’ are abbreviations for Sindarin and Quenya)

“Ñoldor … The name meant ‘the Wise’, …” .

– The War of the Jewels, Quendi and Eldar – pg. 383, 1994

and,

“S. bereth, … spouse, queen”.

– Parma Eldalamberon 17 Words, Phrases and Passages in Various Tongues in The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien – pg. 23, 2007 (‘S.’ is an abbreviation for Sindarin)

Another equally engaging possibility is that ‘Goldberry’ meant ‘Flower Bride’, being ‘worn down’ from:

“S. goloth, … inflorescence, collection of flowers”,

– Vinyar Tengwar 42 – pg. 18, 2001 (‘S.’ is an abbreviation for Sindarin)

and ‘bereth’ as given above.

24 There exists a philological connection dating back to Anglo-Saxon times of those peoples’ naming for ‘female elves’ and earlier Latin language comparable ‘nymphs’:

“2.2 The female ælfe~elven

… at some point in the early Middle Ages, female equivalents of male ælfe entered Anglo-Saxon belief-systems, attested first as equivalents of nymphae.”

– The Meanings of Elf and Elves in Medieval England, Chapter 9: The Meanings of Ælfe – pg. 204, A. Hall, 2004

The above is consistent with definitions presented by Joseph Bosworth. Under a subheading of ‘WÆTER’ we have:

“Wæter-ælf water-elf, a nymph; …”.

– A Dictionary of the Anglo-Saxon Language, J. Bosworth, 1838

Thus, Tolkien’s employed combination: “elf-queen” for a very white-skinned aquatic rooted Goldberry appears historically apt and well-grounded when one also considers that the white water-lily (genus Nymphæaceæ) has long been regarded in England as the: ‘queen of flowers’:

“As a Botanical flower this is considered the queen of British flowers.”

– Flowers, Grasses and Shrubs, Yellow and White Water-lily, and Victoria Regia – pg. 188, M. Pirie, 1860

Its regal beauty has even led to embedment in traditional folk sayings:

“Against St. Swithin’s hastie showers,

The lily white reigns queen of the flowers.”

Although Goldberry has been primarily linked in this article to the yellow water-lily, her true queenly connection to the white water-lily is not revealed till Angel and Demon, Gospel and Fairy-story – Part III.

25 Such a corruption is well within the realm of possibility. Tolkien provided an example for the case of ‘Brandywine’, on which Christopher comments:

“… the Hobbits had ‘twisted into a familiar shape’ the Elvish name Baranduin making out of it Brandywine, … Brandywine was ‘a very possible “corruption” of Baranduin’, …”.

– The Peoples of Middle-earth, The Appendix on Languages – pg. 72, 1996 (Christopher Tolkien’s inserted quotes and italicized emphasis on ‘Baranduin’ and ‘Brandywine’)

26 Frodo exhibited remarkable insight in grasping Goldberry’s Nature-related complexion. Within moments of meeting her, he perceptively sings of ‘spring, summer, lilies and water’. And that, it is worth observing, occurs quite some time before Tom’s pseudo-explanatory rhyme:

“I had an errand there: gathering water-lilies,

…

Each year at summer’s end I go to find them for her,

in a wide pool, …

there they open first in spring …”.

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil (my emphasis)

27 As part of school curricula at King Edward’s, Tolkien was taught botany at the tender age of 8:

“The boys are also (as far up as class 8) instructed in Botany, with the intention of training their powers of observation and evoking an interest in the objects and phenomena of nature.”

– The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide 2006 Edition, Chronology, Autumn term 1900, C. Scull & W. Hammond

Moreover, having already been nurtured in the subject by his mother, it was much to his liking:

“I was eager to study Nature, …”.

– The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, On Fairy-stories, Note D, HarperCollins, 1983

And:

“… (especially botany) …”.

– Tolkien On Fairy-stories, Manuscript B MS. 4 F. 73-120 – pg. 235, V. Flieger & D. Anderson, 2014

28 Note how Tolkien was not just interested in the variety of encountered flora – but also insects. It is high likely he would have understood the ‘nymph’ stage in the metamorphosis cycle of certain kinds. An analogous metamorphosis process symbolized by the motif of the butterfly, but in relation to plants, mythology and ultimately Goldberry is discussed in Part II of this series and The Road to Fairyland – Part II.

29 Sarehole, while Tolkien and his brother lived there, actually lay within Worcestershire. It was incorporated into Warwickshire under a counties line change in 1911.

30 Although some dictionaries classify (or sub-classify) ‘water blobs’ exclusively as white water-lilies, there is no certainty on this matter. For example:

“water-blob(s) … (b) the water-lily, esp. the yellow water-lily, Nuphar lutea; …”.

– The English Dialect Dictionary: Volume VI – pg. 401, J. Wright, 1905

“Water Blobs. Blossoms of Nuphar lutea, Sm., Yellow Water Lily (A.B.); probably from the swollen look of the buds.”

– A Glossary of Words used in the County of Wiltshire – pg. 25, G. Dartnell & E. Goddard, 1893

It appears both varieties of water-lily have been assigned the same nickname. Usage varies regionally:

“Water Blob. …

(2) Nymphæ alba … Northampton; Yorkshire …

(3) Nuphar lutea … Dorset; Northampton …”.

– A Dictionary of English Plant-Names – pg. 484, J. Britten & R. Holland, 1886

Angela Gardener in Black & White Ogre Country asserts that ‘water blobs’ are ‘marsh marigold’. Though also provincially nicknamed so, this author disagrees as marsh-marigold is a plant:

“… native to marshes, fens, ditches and wet woodland …”.

– Wikipedia article on ‘Caltha palustris’ (marsh-marigold)

and invariably,

“… grows in places with oxygen-rich water near the surface of the soil.”

– Wikipedia article on ‘Caltha palustris’ (my emphasis)

In other words it is not found amid deeper running waters requiring wading and possibly even some swimming. Whereas Hilary Tolkien recounts that after removing shoes and stockings:

“Sometimes you had to paddle in order to get the water blobs, …”.

– Black & White Ogre Country, Bumble Dell – pg. 2, A. Gardner, 2009 (my emphasis)

Furthermore, unlike white/yellow water-lilies (see https://www.plantlife.org.uk): “the marsh-marigold is poisonous and can irritate the skin”. In light of Hilary’s implied repeated collection of ‘water blobs’, this makes marsh-marigold a less likely candidate.

31 Invariably English flora are assigned scientific names of Latin derivation, the foundation of which is the Linnaean system.

32 Per Tolkien: A biography, 1977 by Humphrey Carpenter – it’s reported (see Northmoor Road – pg. 160) that the family would pole-up towards quieter stretches of the Cherwell near Water Eaton and Islip. Here, yellow water-lilies are abundant in summer months. Evidently familiarization with punting occurred as a young adult:

“I was brought up to Oxford … in the October of that astonishing hot year 1911, and we found every one in flannels boating on the river. Punts were then as strange to me as camels; but I later learned to manage them.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #254 – 9 January 1964, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

‘Our River’, George Leslie – Punting* on the Cherwell, 1881

‘Our River’, George Leslie – Punting* on the Cherwell, 1881

*Punts have remained fundamentally unchanged – even to this day.

33 The fountain’s current Mercury bronze was acquired in 1928. Prior to this, one had been installed as far back as 1695:

“Tom Quad, … may be seen in Loggan’s drawing of 1675. In 1695 the statue of Mercury … supplanted the globe. The gift of Canon Anthony Radcliffe …”.

– Notes and Queries: A Medium of Intercommunication – pg. 532, Tenth Series Volume II, July – December 1904

We know water-lilies had embellished the basin at least since 1904 (before Tolkien’s arrival in Oxford as an undergraduate) – and probably much earlier:

“ ‘Christ Church College – Tom Quadrangle … a pedestal bearing a figure in bronze of ‘Mercury’ (restored). In reality the figure no longer shows above the water-lilies in the basin, …’ ”.

– Notes and Queries: A Medium of Intercommunication – pg. 532, Tenth Series Volume II, July – December 1904

34 The Roman god Mercury bears some other similar traits to Bombadil in being a trickster as well as a god of luck, travelers, messages and boundaries. His role as a psychopomp mirrors Bombadil as discussed in Angel and Demon, Gospel and Fairy-story – Part I. However, for this article I have only grazed the surface. A much deeper connection of Tom to a mythological Mercury is presented in Angel and Demon, Gospel and Fairy-story – Part II.

35 During the summer of 1926, the Tolkien family engaged in a picnic on the banks of the Cherwell. Michael tripped over some willow-roots and fell into the river. Tolkien senior jumped in and rescued him.

36 Frederic Weatherly of Brasenose College Boat Club, University of Oxford narrowly escaped strangulation by water-lilies after jumping from his vessel at Henley Royal Regatta in 1868.

Popular German literature, Immensee, and the dangers posed by white water-lilies (weisse wasserlilien) may have been part of Tolkien’s Teutonic reading repertoire:

“Every reader of German literature, too, knows the experience of Reinhardt in Theodor Storm’s Immensee (1849), when, in his midnight swim, his body becomes entangled in the ‘weisse Wasserlilien’ …”.

– Studies in Scandinavian Literature and Culture, A Neglected Passage – pg. 96, F. Ingwersen, M. Norseng, 1993

37 We must not get carried away with trying to understand the science behind Goldberry’s underwater breathing mechanism. Clearly, even when surfacing while in her Withywindle pool, she possessed the ability to breathe air. We should not doubt an ability to release a stream of bubbles when submerged if she so desired.

38 One simple method of transference is as follows:

“The Water-Lily may be transplanted from its native home by placing the thick rhizomes in baskets of earth and fastening stones to them, so as to keep them well under water, …”.

– English Botany, Volume I, Nymphæaceæ – pg. 77, Boswell/Lancaster/Sowerby, 1863

It is not impossible to imagine that Tom and Goldberry were already prepared in advance for this annual relocation event. Minimizing the time out of water, would have caused the plants least distress.

Another Anglo-Saxon word for the ‘water-lily’ (other than ‘eadocca’ – see footnote 13) is collon-cróh (sometimes spelled collan crōg). This translates across as ‘water-jug’ or ‘water can’. Hence, a water-holding vessel appears to present a mythical and philological link back to Goldberry’s lily-holding earthenware.

From the website: ‘oldenglish-plantnames.org’:

“collon-crōh

Lehmann (cf. 1907,23-26) gives several explanations, the interpretation based on ‘water-jug, Wasserkrug’ seems most plausible: variant of OHG quella ‘well, Quelle’= OE *colle + OE crōg ‘jug, Krug’; cf. accordingly the ModE name ‘water can’ (Britten / Holland 1886, s.v.) and the G name ‘Seekanne’ (cf. Marzell, 2000,3,358).”

The Anglo-Saxon word may have caught Tolkien’s eye (though there is no proof) as it is singled out by Jacob Grimm in Teutonic Mythology, Volume III, Chapter XXXVII – pg. 1216, 1883 – translated by James Stallybrass:

“collan-crôg is achillea or nymphaea” (my emphasis, nymphaea being a water-lily)

Teutonic Mythology, a set of four volumes which Tolkien likely had easy access to, is an English translation of Deutsche Mythology.

39 One can reasonably infer that if Tom took the lily-leaves, he also carried away attaching tendrils and root rhizomes.

40 The poem has been published in Tolkien Studies, Volume 10 per Tom Bombadil’s Last Song: Tolkien’s “Once Upon A Time” by Kris Swank.

Revisions:

Grammatical, spelling and minor error corrections are not recorded. Neither are minor changes to phrasing that have little bearing as to the thrust of the message being conveyed by the author.

All revisions prior to 2020 are archived. Please contact the author if records are required.

1/30/20 Added section break: “*****” after “English counties.”.

Added: “atop of which white blankets were to be spread”.

Added: “More so because it too undergoes a kind of metamorphosis.”.

Removed: “at this time of year”.

Added: “covering the east and west facing windows”.

Added: “Am I done … sinking towards the evening … – Flowers of the Field, C. A. Johns, 1911 (my emphasis)”.

Removed: “(from a philological standpoint)”.

Added: “Coming full circle … Or imaginatively – near enough!”.

Added: “Where exactly Tolkien first encountered … J.O. Halliwell-Phillipps, 1901”.

Was: “… the lilies would have been hard to miss … while on the Cherwell”, Is: “… these bright points of color would have been hard to miss … while on the drably-hued Cherwell”.

Was: “to recall that when it came to ‘sources’:”, Is: “to recall the importance of personal experiences. For ‘external sources’ Tolkien stipulated that:”.

Added: “(in his self-admitted most formative years)”.

Added: “(titled The quest begun – The loss of Hylas and Hercules)”.

Added: “(a group of visual and literary artists)”.

Removed: “It is also possible that J.W. Waterhouse’s inspiration to paint Hylas and the Nymphs came from the same account as opposed to classical Greek sources or other later renditions.”.

Added: “We can see how significant … ‘Proserpine’ by Dante Gabriel Rossetti”.

Added: “, having already been nurtured in the subject by his mother,”.

Added new footnotes 20, 23 and 25, reordered existing.

2/7/20 Was: “The gold belt and chair”, Is: “The gold belt, chair and her lofty position”.

3/5/20 Was: “seemingly connect”, Is: “most strongly connect”.

Was: “As a specific species of flower”, Is: “For this species of flowering water-flora”.

Was: “Goldberry being “young” and vibrant closely associates her with”, Is: “Goldberry being “young” and vibrant and vernal-voiced closely associates her to”.

Added: “- though it isn’t known whether this particular work was part of the discussion”.

3/27/20 Added: “Surely then – we should acknowledge … Bosworth, 1813”.

Added new footnote 17, reordered existing.

4/10/20 Was: “principle Tolkien recommended”, Is: “principle, for fantasy creation, Tolkien identified”.

Added: “, and work with scenic imagery of a natural pool Tolkien himself provided us,”.

Was: “the Northern hemisphere”, Is: “what is now continental Europe”.

Added: “Tolkien’s self-specified”.

Added: “Or from its head – many curly filaments conveying imagery of yellow rippling hair?”.

Added: “This book is recorded … & Wayne Hammond)”.

4/19/20 Added: “At the University of Oxford … C. Kilby, 1982”.

Added: “Though, one can surmise Frodo sang of Goldberry’s bubbly breath … given a welfare concern,”.

4/25/20 Added: “Known as phototrophs – being stimulated by light, or its absence”.

Added: “(or sub-classify)”.

Added: “For example: … G. Dartnell & E. Goddard, 1893”.

5/7/20 Added new footnotes 19 and 26, reordered existing.

5/15/20 Added: “* Tolkien appears knowledgeable on this matter … in Letter #93.”.

Added four pictures of creatures atop water-lilies in footnote 17.

Added: “, the foundation of which is the Linnaean system”.

5/31/20 Added Letter #165 quote.

Added: “Hmm … to briefly summarize then: … depth behind the episode.”.

Was: “recover the Golden Fleece”, Is: “wrest away the Golden Fleece”.

6/23/20 Was: “naiad-like creatures”, Is: “sensual water-creatures”.

Added: “Popular German literature, … F. Ingwersen, M. Norseng, 1993”.

6/29/20 Added: “In light of … a less likely candidate.”.

7/8/20 Added quote from Joseph Wright’s The English Dialect Dictionary.

7/12/20 Added painting of Proserpine.

Added: “However Tolkien’s acquaintance with the Pre-Raphaelites stemmed from pre-university days.”.

Added section break: “*****” after photo of yellow water-lily buds.

7/16/20 Added: “It is quite apparent that ‘Brandywine’ … Both aspects are distinctly un-English.”.

Added new footnotes 19 and 20, reordered existing.

7/28/20 Added: “It doesn’t take much to visualize … these banks was a favorite picnic spot.”.

Added picture of Cherwell at Sparsey Bridge with accompanying starred note.

8/3/20 Added new footnote 24, reordered existing.

8/13/20 Added: “They naturally occurred in other areas of the university grounds too:”.

Added quote from Historic Towns Oxford.

Added: “And how by autumn … opening out to their fullest.”.

8/21/20 Added: “Most pertinently Tolkien tells us: … classification of plants; …”, & sources of quotes.

8/25/20 Was: “when budding”, Is: “when budding in spring and summer”.

Added: “One might deduce that Tolkien’s logic … rise to its naming by Hobbits.”.

8/31/20 Added: “Nor should we forget that Tolkien declined … giving more realism to the projected imagery.”.

9/2/20 Added item (iv) to footnote 4.

Added: “The yellow water-lily’s medieval Latin … the etymology of this river-plant.”.

9/20/20 Was: “matches well”, Is: “partially matches splendidly”.

Added: “a couple of things about the aquatic … more importantly – present were”.

Was: “stood proud yet in a green pool”, Is: “One which stood proud atop an expansive yet semi-submerged green leaf. Or perhaps even within a green pool”.

Added new footnote 3, reordered existing.

Added: “(past the point of amendment)”.

Added: “with its white relation”.

Added: “Especially how earlier while in the Old Forest we are told:”.

Added quote and source: “White mists began …”.

Added: “The above is consistent … subheading of ‘WÆTER’ we have:”, and ensuing quote.

Added: “Although Goldberry has been primarily … revealed till Angel and Demon, Gospel and Fairy-story – Part III.”.

Added: “It appears both varieties of … J. Britten & R. Holland, 1886”.

10/13/20 Added: “with flukes or legs – or whether”.

Added: “(instigating motion)”.

Added: “In the English language … ‘v’ and ‘ph’ is unknown.”.

10/23/20 Removed: “the origins of their names.”.

Added new footnote 27, reordered existing.

Was: “botanical and etymological interests”, Is: “botanical and entomological interests”.

11/16/20 Added: “One simple method of transplanting … caused the plants least distress.”.

12/1/20 Added: “But perhaps most appropriately, Tolkien … arrival in Oxford as an undergraduate.”.

Added new footnotes 29 & 30, reordered existing.

Added photo of ‘The Mercury Fountain’.

1/15/21 Added: “One can see then – how opportunities … Niekas interview (see Tolkien Studies 15, pg. 163), 1967 (my emphasis)”, followed by section break.

Added poetry quote from Thomas Moore’s Paradise and the Peri.

2/15/21 Added: “A much deeper connection of Tom to a mythological Mercury is presented in Angel and Demon, Gospel and Fairy-story – Part II.”.

2/23/21 Was: “meaning ‘Elvish Queen’.”, Is: “glossed as ‘Elvish Queen’ or ‘Wise Elf Queen’.”.

Added new footnote 20, reordered existing.

3/1/21 Added: “However for this article I have only grazed the surface.”.

4/14/21 Added: “(also known as Wood Eaton)”.

Added: “Backing up a prognosis of an assimilation … between the Brandywine and the Old Forest.”.

4/29/21 Was: “in Tolkien’s teen years”, Is: “as a young adult”.

5/25/21 Added: “Given the small size … contrived artistry.”.

12/5/21 Added new footnote 4, reordered existing.

Added: “(water nymphs of a spring, river or waterfall)”.

12/6/21 Added: “not iris foetidissima”.

Added: “Though also provincially nicknamed so,”.

1/3/22 Added: “With his mother, Mabel, … for joint examination:”.

Added quote: “His mother taught … became very knowledgeable.”.

2/16/22 Was: “my own inclination ties in with Hooker’s in that”, Is: “my own inclination is that”.

Added: “; though frankly, Tolkien provided an unconvincing association”.

5/12/22 Added: “Pre 1934, there is no record of any of Tolkien’s children possessing toys with names assigned from his body of Silmarillion myths.”.

Added: “Given how his mindset was such that: … foothold in his fictitious world.”.

5/18/22 Added: “Nor those housed in his own Exeter College (e.g. The Adoration of the Magi by Edward Burne-Jones).”.

5/28/22 Added: “And Tolkien readily confessed: … Then”.

7/19/22 Added “- especially as the ‘ph’ in Nenuphar is pronounced as if it were ‘f’.”.

8/1/22 Removed all section breaks: “*****”. Added sub-section titles, 5 places.

10/3/22 Was: “Water-lilies – Look Again!”; Is: “Introducing the Yellow Water-lily”.

Added new sub-section title: “Look Again and Reimagine the Familiar!”.

3/3/23 Added: “, a set of four volumes which Tolkien likely had easy access to,”.

8/21/23 Added new footnote 11, reordered existing.

9/30/23 Added new footnote 16, reordered existing.