Part IV: Elementary My Dear … What’s It?

A Peculiar but Wholesome Relationship

Even at the very early stages of drafting The Lord of the Rings storyline featuring Tom and Goldberry – Tolkien put considerable thought into the characters he wished to cast, in addition to the depth of the narrative. In February 1939 having shaped just a few chapters he confessed:

“The writing of The Lord of the Rings is laborious, because I have been doing it as well as I know how, and considering every word.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #35 – 2 February 1939, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

Much later he confirmed the book:

“… was written slowly and with great care for detail, …”.

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #328 – Autumn 1971, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

No doubt, just like his Silmarillion tales, much of the initial effort for the new adult-oriented fairy-story was directed towards:

“… the construction of elaborate and consistent mythology …”.

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #19 – 16 December 1937, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

And the end result was a:

“… coherent structure which it took … years to work out.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #190 – 3 July 1956, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

20 Northmoor Road, Oxford – where The Lord of the Rings began

Yet at first read there seems to be ample incoherence and some off-putting inconsistencies surrounding our idyllic couple. Indeed, even seasoned readers have felt the side activity between the hedge-border of Buckland, and entrance to Bree was unnecessary. Opinions have often been voiced that Tolkien left a distraction which never added much value to the overall tale. It has been argued an omission would have rid Middle-earth of two of its ‘weirdest’ characters. And to some – that would have been no major loss.

However, Tolkien’s purpose was for the hobbits to experience:

“… an ‘adventure’ on the way.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #153 – September 1954, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (Tolkien’s emphasis)

Yet what an adventure! As we shall see in future articles – there was much more to it than meets the eye. Much more than any reader has realized to date. But to truly understand what happened and unveil the book’s deepest secrets – we will first need to study our odd couple in microscopic detail, because vital clues have been missed by all and sundry.

Now when it comes to the merry duo – quite rightly the reader is entitled to be a little perturbed. Here we have the unusual situation of an overly energetic wrinkly old man cohabiting with a beautiful young maiden who exhibits a degree of worrisome servility1. The contrast in looks and dress code – from ancient and stout with a wardrobe of inelegance, to youthful grace with stylish garb – cannot be missed. Most peculiarly, both of them sang to an extent what many consider beyond the ordinary; while oddly – even much talk resembled rhyme. And some of this ineloquent (seemingly nonsensical) verse is decidedly annoying. To make matters worse, comic relief was added of the strangest kind in belittling the power of the Ring. Crassly put maybe – still it is understandable how one can generally enjoy The Lord of the Rings, yet actively dislike Tom and Goldberry.

The age disparity between the merry pair is certainly a matter which has been frowned upon. Without foreknowledge of the 1934 The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, a casual reader could have been easily confused over their exact relationship. One can sympathize how for a mid-50’s BBC broadcast, with perhaps just The Lord of the Rings at-hand, a presenter might automatically have assumed non-marital rapport. Tolkien was obviously aghast at the misconstrual:

“… worse still was the announcer’s preliminary remarks that Goldberry was his daughter (!), …”.

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #175 – 30 November 1955, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

Yet another point of mixed feelings is signs of a scandalous abduction or even elopement! In the poem: The Adventures of Tom Bombadil – Tom forcibly removes Goldberry from her habitat and then seemingly coerces her to be his wife. The situation is a little muddy as some view her as a tad flirtatious and the departure from her river abode as a happy event. Her mother, the ‘River-woman’, although falling short of voicing disapproval, clearly misses her presence:

“… on the bank in the reeds River-woman sighing …”.

– The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, 1934 (& 1962) poem

Whether we readers like it or not, there exist slight undertones of a kidnap followed by some brainwashing – resulting in a subtly sinister aspect to the episode. Tom flaunted a ruthless streak as evidenced by the way he dealt with Old Man Willow and the Barrow-wight. Hints of this trait can be glimpsed in the Bombadil goes Boating poem. Though much was said in jest, the hobbits of Buckland were certainly wary of him with their verbal raillery being:

“… tinged with fear …”.

– Preface to: The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, 1962

Undeniably the implication of the taunt:

“ ‘… you’ll find no lover!’ ”,

– The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, 1934 (& 1962) poem

is that Tom would become Goldberry’s lover. Whatever the sexual connotations, negatively compounded by mismatched ages, to Tolkien – Tom was not the stereotypical ‘dirty old man’. Far from it, I do deem. As a devout Christian raised in staid Victorian/Edwardian societies where ‘sex’ was practically a taboo subject, Tolkien may never have realized an issue would even arise in the minds of some readers. Yet how can we fault him for not anticipating or catering to our more liberal yet more critical world of the 21st Century?

To the Professor, one can surmise, Tom and Goldberry represented an ideal couple blissfully in love, and in harmony with all ‘good’ and natural creatures within very discretely defined lands. Many have compared the pairing to Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, and maybe such an arrangement was deliberately so portrayed. Married in the eyes of God, with the local animals being auspicious witnesses, is not too unlike the state of the first couple in their first dwelling. And this biblical face is, for now, more so reflected in Goldberry. For being a source, per my proposal of Part III, she is indeed Eve-like.

‘Adam Digging and Eve Spinning’, Medieval Painting – wall of Broughton All Saints Church, England

Beyond companionship, Tom offered Goldberry a great deal. He provided wisdom, knowledge, protection, laughter, a new home and refreshingly – a new way of life. Instead of aquatic fare, the food on Tom’s table was from the soil and animal produce. It was a different type of existence – which nonetheless Goldberry neatly slotted into while still being nearby her old haunt. There are absolutely no signs that ‘Master’ Bombadil constrained Goldberry in any way, or that she was unhappy. She displayed tolerance to her husbands’ songs and complemented them with her own. For the reader at least, the one verse explicitly vocalized was far from irritating unlike his oft repetitious lilt.

Understanding Goldberry’s Genus: A Way Forward

Despite all of these interesting matters, when it comes to Goldberry, there are still a couple of loose ends that need tying up. One of these is identifying the type of creature she represented in Tolkien’s mythology. The other is the River-woman. Beyond the obvious, who was she? What was she? And if Goldberry was a literary source of some of our world’s mythological water-maidens (as suggested in Part III) was her mother something even more basic?

We must ask ourselves, why is there no sign of her blessing the wedding? Had Tom forbidden her attendance at the marriage ceremony? Had he quarreled with his future mother-in-law? Why does Goldberry visit her mother’s pool only once a year? Was Goldberry a bad daughter in forsaking kin for Tom? Why had she become so estranged when the Withywindle was relatively close by? And where in all this is Goldberry’s father? Questions upon questions arise – if we choose to let them!

To attempt to tackle these seemingly unanswerable mysteries, we must employ logic and once more try to fathom Tolkien’s underlying purpose. In particular, we must once again heed his remarks on myth and invention:

“But an equally basic passion of mine ab initio was for myth …”,

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #131 – late 1951, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (Tolkien’s italicized emphasis on ‘ab initio’)

“… I am interested in mythological ‘invention’, and the mystery of literary creation (or sub-creation as I have elsewhere called it) …”.

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #180 – 14 January 1956, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (Tolkien’s emphasis)

From its inception Tolkien desired to create a new tale which not only linked to our history, but also our mythologies:

“After all, I believe that legends and myths are largely made of ‘truth’, and indeed present aspects of it that can only be received in this mode; and long ago certain truths and modes of this kind were discovered and must always reappear.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #131 – late 1951, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (Tolkien’s emphasis)

And so for Goldberry being a forerunner from deepest antiquity, as advocated in Part III, ‘Myth and Fairy tale’ could reasonably be added to the statement:

“Legend and History have met and fused.”

– The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, On Fairy-stories – pg. 156, HarperCollins, 1983

Just like his creation of Sellic Spell, which was an attempt to imaginatively reconstruct the fairy tale which he believed lay behind Beowulf, I believe the Professor tried to make sense in his own mind of our world’s supernatural water-maidens. And so ingeniously the idea developed to make his great fairy-story their ultimate source. To strengthen such a postulation, I have had to dig deep and ponder upon the roots of European mythologies. For I have a sneaking suspicion, as I have already alluded to in Part II, that there was a tad more to the essence of Goldberry and her mother that we can glean. To piece together the few rudimentary clues available – we must more assiduously examine the case for these two creatures ultimately belonging to the legendary race of ‘elementals’.

Earthlings: Soulless Elementals tied to Mother Earth

Mankind’s belief in elementals goes back to a time before Christianity. Ancient peoples held a doctrine that inanimate things (and even animals and plants) had souls of their own. However the concept of an after-life for them was far from universal. Many believed, upon death, those soul-forms effectively regressed to chaos; a dispersion back into Mother Nature as the components of their constitution were incapable of manifesting any higher spiritual activity. Effectively then, all parts of their makeup were tied to planet Earth forever.

Early Christians took the spiritual side a step further by developing theologies of dichotomy and trichotomy2. All living beings possessed body (soma) and spirit (pneuma) but it was only man to whom God had gifted a soul (psyche). At physical expiry, all spirit and body would dissolve into the basic matter making up the planet. However man being a special life-form meant his unique soul – an imprint of his very essence – was predestined to depart the world and reach a higher plane of existence.

A slightly different and more complex flavor developed in Teutonic mythology:

“… of men the spirit is immortal, but the body mortal, and of beasts both body and soul are mortal; so Berthold …. allows being to stones, being and life to plants, feeling to animals. Schelling says, life sleeps in the stone, dozes in the plant, dreams in the beast, wakes in man.”

-Teutonic Mythology, Chapter XXI, Vol IV – pg. 1478, J. Grimm – translated by J.S. Stallybrass

In any case, by the time of the European Renaissance some of those storied metaphysical forms of life, seemingly not of flesh and blood or plant-matter, were termed ‘elementals’ and, perhaps confusingly so, cast under the general designation of fairies or fays. Paracelsus in the 16th century classified true elementals as belonging only to inanimate matter – specifically four of the ancient Aristotle elements: air, water, earth and fire.

‘Paracelsus’ (Philippus von Hohenheim), 1493-1541

Given such mythology has roots in some our world’s most ancient literature, and undoubtedly Tolkien’s early3 knowledge of that, we are obliged to consider whether he included elemental-type entities in his writings. If so, we ought to consider whether there is sufficient evidence implicating Goldberry and maternal kin to be of that race too. Exactly why should we follow such a path? Well – because Paracelsus’ elementals of water were water-maidens that he’d titled: Undines!

Now to the best of our knowledge in very early hierarchy Tolkien had already pigeonholed many of our world’s mythological creatures – though inhabiting our physical planet – as originating outside of it:

“… the Mánir and the Súruli, the sylphs of the airs and of the winds.”

– The Book of Lost Tales I, The Coming of the Valar and the Building of Valinor – pg. 66

“… brownies, fays, pixies, leprawns, … for they were born before the world …”.

– The Book of Lost Tales I, The Coming of the Valar and the Building of Valinor – pg. 66

Belonging to the mix were mythological water-spirits. Because The Book of Lost Tales I tells us aquatic entities (the Oarni, Falmaríni and Wingildi – see pg. 66) accompanied the greatest of the Ainur upon their arrival in Arda.

One can thus reasonably conclude that at this early stage of development:

(a) Tolkien had familiarized himself with elementals, for ‘sylphs’ was a word coined by Paracelsus.

(b) An origin outside of the physical Universe made such creatures divine.

.jpg)

‘The Salamander – Elemental of Fire’, Paracelsus’ ‘Auslegung von 30 magischen Figuren’

In this same general time period a telling note points to him pondering on classifying some mythical female water-beings, namely mermaids4, as either:

“… earthlings, or fays? – or both …”.

– The Book of Lost Tales II, The Tale of Eärendel – pg. 263

If I were to take an educated guess, pre-The Lord of the Rings Tolkien wasn’t quite sure where mermaids should be placed because of possibly belonging to another wholly different category to divine fays5; an ethnological category he obviously termed: “earthlings”. But exactly what were they?

Our best evidence can be found in an early ~1920’s document called The Creatures of the Earth. Within, he labeled ‘Earthlings’ as: wood-giants, mountainous-giants6, pygmies7 and dwarves8. Listed below ‘Earthlings’ in a pseudo-hierarchical ‘chain of being’ were: ‘Beasts and Creatures’ and then ‘Úvanimor/Monsters’. If I were to hazard another guess, ‘Earthlings’ were mentally grouped with others (I suspect with those further down the chain) as those whose bodily matter was destined to remain within the confines of the planet, and whose spiritual essence, upon death, eventually dissolved into nothingness or spread into nebulous impotency. Indeed, if that were the case ‘Earthlings’ would be highly befitting terminology.

‘The Great Chain of Being’, Rhetorica christiana, 1579

Earthlings in The Lord of the Rings

When it came to drafting up the Bombadil chapters, there is more evidence that Paracelsian-type elementals were intended to be part of Middle-earth’s rich racial diversity. Old Man Willow was referred to as a:

“… grey thirsty earth-bound9 spirit …”.

– The Return of the Shadow, Tom Bombadil – pg. 120 (my emphasis)

And then a description of Trolls was given as:

“… stone inhabited by goblin-spirit, …”,

– The Treason of Isengard, Treebeard – pg. 411 (my emphasis)

with the point being that even inanimate matter in Tolkien’s world could be possessed by a spiritual essence.

Even more telling is a preliminary note for his ‘Fairy Stories’ address. While in the process of gathering thoughts in drafting those Bombadil chapters, Tolkien was also engaged in preparing for the Andrew Lang Lecture of 1939. It is notable that when contemplating a tree-fairy, he acknowledged that though spiritually originating before creation, and:

“… immortal while the world (and trees) last …”,

– Tolkien On Fairy-stories, Manuscript B MS. 6 F 6-8 – pg. 255, V. Flieger & D. Anderson, 2014

most revealingly for us:

“It is possible that nothing awaits him – outside the World and the Cycle of Story and of Time.”

– Tolkien On Fairy-stories, Manuscript B MS. 6 F 6-8 – pg. 255, V. Flieger & D. Anderson, 2014

Again, this evokes the fate of a Paracelsian ‘elemental’, and probably parallels the destiny of his ‘Earthlings’. Sadly though, for such creatures, he felt from a Christian belief and an afterlife perspective – this state of affairs was:

“… a dreadful Doom …”.

– Tolkien On Fairy-stories, Manuscript B MS. 6 F 6-8 – pg. 255, V. Flieger & D. Anderson, 2014

Still, one can understand how the genus of tree-fairies might have been debatable having potentially fallen under a couple of different classifications. Just like mermaids – they might have been:

“… earthlings, or fays? – or both …”.

– The Book of Lost Tales II, The Tale of Eärendel – pg. 263

Which from a historical perspective aptly reflected blurred borders present in medieval accounts of supernatural creatures:

“Such things do not admit of clear classifications and distinctions.”

– Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics, Sir Israel Gollancz Memorial Lecture, 1936

Which is echoed by our understanding of Anglo-Saxon terminology through their lumping together of different female water-entities:

“wæterelfen … water-elf, mermaid, nymph.”

– A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary – pg. 338, J.R. Clark Hall, 1894

‘Tree Fairy, Cindi and Mama Tree’, Grimm’s Fairy Tales – Illustrated by Arthur Rackham, 1917

As to the published The Lord of the Rings, again there are further hints that an inert substance could possess a latent ‘fea’. In Legolas’ words during the Fellowship’s journey through Hollin:

“ ‘… Only I hear the stones lament them: …’ ”.

– The Fellowship of the Ring, The Ring goes South

As if to provide emphasis, italicized in the voices of the stones themselves:

“… deep they delved us, fair they wrought us, high they builded us; but they are gone.”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, The Ring goes South

Legolas wasn’t lying here – but though these particular elementals were innocuous to the quest, others were not so benign. Tom Shippey goes as far as finger-pointing the storm on Caradhras to be the work of presumably malevolent:

“… elementals …”.

– J.R.R. Tolkien Author of the Century, Chapter II – pg. 67, T.A. Shippey

Perhaps the strongest evidence and most obvious elemental candidate comes from Tolkien expounding on the nature of Stone-trolls. Worked on by Dark Powers, such creatures were fundamentally preexisting spirits inhabiting stone. These barbaric monstrosities of our world’s Norse mythology were readily included into his writings, yet he heavily hinted they lacked the same as that which typified all elementals, namely – a soul:

“… when you make Trolls10 speak you are giving them a power, which in our world (probably) connotes the possession of a ‘soul’. But I do not agree (if you admit that fairy-story element) …”.11

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #153 – September 1954, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (Tolkien’s additional italicized emphasis on ‘speak’)

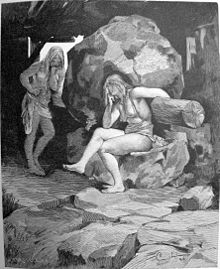

‘Meeting the Troll’, from The Boy Who Had an Eating Match with a Troll,

illustrated by Theodor Kittelsen in Norwegian Folktales by Asbjørnsen and Moe, 1884

Tolkien’s pointed rejection of ‘speech’ to being a requisite for possessing a ‘soul’ reflects a longstanding debate and the lasting influence of his renowned Oxford predecessor – Max Müller, Professor of Philology. An academic who had even challenged Charles Darwin, Müller’s views and works ought to have been well-known to Tolkien:

“There is in man a something, I am not afraid to call it for the present an occult quality, which distinguishes him from every animal without exception. We call this something reason when we think of it as an internal energy, and we call it language when we perceive and grasp it as an external phenomenon. No reason without speech, no speech without reason. Language is the Rubicon which divides man from beast, and no animal will ever cross it.”

– Max Müller and the Philosophy of Language, Darwin and Max Müller pgs. 14-15, L. Noiré, 1879

That magical internal energy we humans were so lucky to have, allowing us to use complex reasoning via language, was down to our gifted ‘souls’. But just because beasts and monsters in fairy tales could communicate employing equally sophisticated speech – didn’t mean they too were endowed with souls. So Tolkien disagreed with the ability to talk being a divide:

“In summary: I think it must be assumed that ‘talking’ is not necessarily the sign of the possession of a ‘rational soul’ or fëa.”

– Morgoth’s Ring, Myths Transformed – pg. 410 (Tolkien’s emphasis)

Because the heart of the matter is that from a mythology/fairy tale standpoint, Trolls as life-forms had ‘Mother-Nature’12 spiritual origins. All four Paracelsian elementals had life:

“… by means of the Vulcanus indwelling in them, which is not a personal spirit, but a virtus, which is the power of nature …”.

– The Paracelsus of Robert Browning, The Philosophy of Paracelsus – pg. 49, C.P. Denison, 1911

Quite possibly – Tolkien thought there was no place for the spiritual essence of Trolls beyond the physical circles of the World. There was no hall where their spirits were to be gathered upon Earth, and there would be no place for them Outside at the end with Ilúvatar. In effect, they were soulless creatures; and ones associated to the ‘earth’ of Paracelsian lore.

Such was the impact of Paracelsus’ teachings that they began to spread – eventually to become embedded in north-European folklore and fairy tales:

“… Katrine knew well that the Troll has no soul. He may live a thousand years; but at the end of them he must die forever.”

– Katrine and the Troll, H. Holdich, The Independent, Volume 31 – pg. 27, 27 February 1879 (my emphasis)

“Now of old the isle of Rügen was full of Dwarfs and Trolls,

The brown-faced little Earth-men, the people without souls; …”.

– The Complete Poetical Works of John Greenleaf Whittier, 1894 Issue – pg. 138, The Brown Dwarf of Rügen – Originating from Arndt’s Märchen of 1816 (my emphasis)

Nonetheless, the theology dictated that elementals still:

.“… have flesh13, blood, and bones; they live and propagate offspring; they eat and talk, act and sleep, etc., …”.

– The Life and the Doctrines of Paracelsus, Pneumatology – pg. 151, F. Hartmann, 1910

All in-line with Tolkien’s portrayal of troll physiology:

.“… Frodo … stooped, and stabbed with Sting at the hideous foot. … the foot jerked back, … Black drops dripped from the blade …”.

– The Fellowship of the Ring, The Bridge of Khazad-dûm

‘The Children and the Stone Troll’, John Bauer, 1915

Now the “fairy-story element” for a soulless ‘water’ entity is best illustrated by the fortunes of Undine. Because of her resemblance to mermaids of myth and Tolkien’s connecting referral to “earthlings”, it is to her and duly Goldberry that I must next turn.

Withywindle Women and their Mythological Makeup

Tolkien once pointed out that:

“… nymphs, … had quite distinct mythological or imaginative origins, …”.

– Jack: A Life of C.S. Lewis, Into Narnia – pg. 312, G. Sayer, 2005

His friend C.S. Lewis was well-aware14 of Fouqué’s nymphean tale of:

“… Undines who acquired a soul by marriage with a mortal …”.

– Letters to Malcolm, Letter #22 – pg. 158, C.S. Lewis, 1964 (my emphasis)

And no doubt Tolkien with his extensive interests in fairy tales and mythology knew it too.

‘Fountain of Undine’, Kurpark, Baden, Germany

Fouqué himself best summarizes Undine’s dreadful plight and that of other types of elemental15:

“ ‘… We should be far superior to you, who are another race of the human family, – for we also call ourselves human beings, as we resemble them in form and features – had we not one evil peculiar to ourselves. Both we and the beings I have mentioned as inhabiting the other elements vanish into air at death and go out of existence, spirit and body, so that no vestige of us remains; and when you hereafter awake to a purer state of being, we shall remain where sand, and sparks, and wind, and waves remain. Thus we have no souls; the element moves us, and, again, is obedient to our will, while we live, though it scatters us like dust when we die; …’ ”.

– Undine, F. de La Motte Fouqué, Project Gutenberg E-book, Chapter 4, produced by S. Laythorpe & D. Widget (my emphasis)

The mortality of ‘man’ was thus a bestowal by our Maker. A largely unappreciated gift, but nonetheless a most precious thing which even long-lived legendary creatures (including undines and mermaids) found supremely desirable. For being truly human meant intrinsic possession of a ‘soul’, a ‘ticket to an afterlife’ and a guaranteed ‘eternal’ existence. At least that was the case in Fouqué’s and Andersen’s classic merwoman fairy tales. Two tales whose principles were faithfully followed in The Lord of the Rings, and I strongly suspect very much on his mind when he stated for mankind:

“… ‘mortality’ is thus represented as a special gift of God … a legitimate basis of legends.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #153 – September 1954, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (Tolkien’s emphasis, my underlined emphasis)

If we “admit that fairy-story element” – then indeed we can see how and why Tolkien meshed an Undine-like Goldberry into the 1934 The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, and then her entirely land-based married portrayal in The Lord of the Rings. Within the latter there are perhaps just the faintest of clues indicative that her makeup and consistency was something special.

Tom poetically described Goldberry as:

“… clearer than the water.”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, The Old Forest

And then as if to reinforce the point, Tolkien had Frodo practically repeat it:

“ ‘… clearer than clear water! …’ ”.

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

Hmm … in acquiring a soul had she transformed from a ‘water elemental’ into an akin embodied creature, yet retained much of those intrinsic former qualities? Had she now become what we might term – a fairy being?

Then we shouldn’t ignore additional evidence pointing to an elemental type essence as revealed by the light of a candle which shone through Goldberry’s hand:

“… like sunlight through a white shell.”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

Unusual, I deem, for a hand shielding the flame from a draft – for fingers ought not to be splayed open!

All of these interesting observations aid a needed reconciliation of the River-woman. Because a logical reason why sightings of Goldberry’s mother were not commonplace is that in the sense of a physical anthropomorphic being (as we might imagine) – the River-woman simply wasn’t one! For perhaps, to Tolkien, she had yet to fully transmute? Though equally possible – she remained invisible16 to all but gifted beings such as Tom and Goldberry herself.

Rivers in European mythologies17 were often inhabited by female spiritual forms. In English tradition – as set down by Michael Drayton in his 1612 Poly-Olbion – daughter, mother and father spirits were resident guardians of both minor and major waterways. With the daughter spirits depicted as water-nymphs (see especially the Cherwell below) – one can understand why such literature readily provided a mythological link back to Tolkien’s world.

Extract from Michael Drayton’s ‘Poly-Olbion’

(courtesy of The Bodleian Library)

Tolkien in The Lord of the Rings refers to Goldberry as the river’s ‘daughter’ four times and explicitly the ‘River-woman’ is mentioned once. But it is possible the Withywindle was viewed as housing a non-conventionally embodied entity, yet also a source of shelter and nourishment for a more conventional fully morphed human-like being.

So the Withywindle (in Tolkien’s mind) may have had another resident/visiting female spirit but not always a flesh-clad tangible one as mortals could see. For it is quite possible that at the time of writing the early Bombadil poetry, Tolkien thought that the ‘mother’ spirit of the river (or an adjoining one) was largely elemental in form and locked within the water itself (yet able to move with the flow or against it). Just like the malevolent willow wasn’t really a ‘man’, perhaps she didn’t go out of her way to display herself as an anthropomorphic ‘woman’.

Against this, in the poem The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, Goldberry’s mother is seemingly situated outside of river waters when lamenting her loss:

“… on the bank in the reeds River-woman sighing …”.

– The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, 1934 (& 1962) poem

But perhaps she wasn’t permanently locked in and possessed the ability to survive for short periods on its fringes.

Alternately Tolkien possibly viewed the reeds on the bank, whose roots connected down into the water, as osmotically acting like the ears of the River-woman’s spirit. News from afar carried by the wind and reverberating in the flora may have been a way of capturing the river “sighing” in mourning its loss. And so the departure of Goldberry, a being who had added such merriment and beauty to the local habitat, would have been sadly detrimental to the whole river-valley’s essence in a spiritual way.

‘The little waves seemed to sob as they whispered, ‘Alas! alas!’18,

Undine, Friedrich de La Motte Fouqué,

Editor: Mary Macgregor, Illustrator: Katharine Cameron, 1907

We also have to remember that when it comes to poetry, every matter should not be taken literally. We must remind ourselves that many details of the hobbit composition must have come from Tom himself – some of which might have become slightly distorted in translation to jest-ridden rhyme. Especially as the final result was:

“… made up of various hobbit-versions of legends concerning Bombadil.”

– Preface to: The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, 1962

If we choose to adopt a ‘looser’ reading of the poetry and text and follow English tradition ala Michael Drayton, the many problems associated to Goldberry’s parentage can be wholly eliminated. If we choose to embrace the evidence and view Goldberry and her mother as ‘elementals’ in constitution – some puzzling text in The Lord of the Rings becomes readily explainable.

Goldberry’s Genus

Yet despite all the analysis presented in this four part series, the astute reader will have noticed a failure to address that all important question: ‘What type of creature does Goldberry represent in Tolkien’s mythology?’ No, an answer of ‘elemental’ simply won’t cut it. Because Tolkien never explicitly referred to such a category in The Lord of the Rings. Nor did it appear among his many papers comprising the Silmarillion myths. So unfortunately, my answer has to be gleaned from what little we have. The good news, especially for scholars, is that the proposal entails a judicious connection to one of Tolkien’s written works. And like it or not – to complete our understanding, a mythological genus must be provided. For it is inconceivable that Tolkien assimilated Goldberry without giving thought to her race.

No Goldberry wasn’t of elvish stock per Frodo’s first impression of being:

“… answered by a fair young elf-queen …”.

– The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil

Through the ages much confusion had arisen in the folklore of Europe. Elves19 and fays had interchangeably been termed ‘fairies’ by men resulting in bafflement and muddled accounts. In such sightings and reports – distinctions were seldom clear cut. Though to be fair – one should acknowledge that both elves and fays were creatures of Faërie and thus technically ‘fairy folk’ or even ‘fairies’. Nevertheless, if not an elf, shouldn’t we consider the possibility of Goldberry being a fay?

So if we peer back to Part I – we must acknowledge how Tolkien desired water-lilies along with their pool setting to play a decently large part in both The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and The Lord of the Rings. Even earlier he had decided to include them in a very limited Elven vocabulary called Qenya. Only one species was singled out:

“… nénu ‘yellow water-lily’, and nénuvar ‘pool of lilies’ …”.

– The Book of Lost Tales I, Appendix – pg. 248

And so as we have also seen, despite all of Goldberry’s interesting makeup and character sourcing – her later imaginative resemblance to the yellow water-lily along with themes of an aquatic habitat – remain dominant. Even in Tolkien’s last writings of her in the poem Once upon a Time – she is depicted next to a ‘lily-pool’:

“Goldberry was there in a lady-smock

blowing away a dandelion clock,

stooping over a lily-pool

and twiddling the water green and cool …”.

– Winter’s Tales for Children 1, Once Upon a Time, C. Hillier, 1965

Thus, I must conclude, for The Lord of the Rings20 she is a water-fay (what we might term a ‘water-fairy’). More specifically, per Christopher Gilson and Patrick Wynne’s detailed study of different types21 of fay listed in Tolkien’s The Creatures of the Earth22, Goldberry is of the ‘nenuvar’ – a Water-fay of lily-ponds!

“Among the Water-fays, the nenuvar23 are probably fays of lily-ponds …”.

– The Creatures of the Earth, J.R.R. Tolkien, see Parma Eldalamberon XIV (my emphasis)

Of course, with what we know today, once again I reiterate that absolute proof remains elusive. However, I’m positive this four part series has meaningfully added to our understanding of Tolkien’s very mysterious little water-lady. The good news is that I am far from finished with Goldberry. In articles to come we will see how she, through an inspirational water-lily theme, is connected to Welsh lake-fairies24, more strongly to religion25 and finally to Estonian fairy tale26. Indeed, there are many more explanatory nuggets Tolkien withheld – and the revelations to come about this couple will surprise even the most attentive and scholarly among us!

Onward to the next set of articles in the series:

What a Colorful Pair!

Footnotes:

1 Goldberry refers to Tom as ‘Master’ or ‘master’ four times. In this day and age such a term of address between a husband and wife has distinct subservient undertones. Even though the following quote dates from 1969 – undoubtedly Tolkien would have known the negative connotations associated to ‘master’ at the time of writing the ‘Bombadil chapters’ beginning in 1938:

“As for Master: … In high uses it would be presumptuous and profane to adopt such a title; in lower uses it is conceited.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #309 – 2 January 1969, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

2 One source Tolkien ought to have been familiar with is the South English Legendary:

“For example, the ‘Legend of St Michael’ in the thirteenth century South English Legendary describes a tripartite soul: humans share the first soul with trees and other plants, this being the soul of substance; … the second soul is that of the spark of life and breath, which humans share with other animals … According to the Legend of St Michael, these first two souls die with the body. But the third soul is spiritual in substance and shared with angels – this soul is immortal …”.

– ‘Fairy’ in Middle English Romance – pgs. 50-51, C.A. Cole, University of St Andrews, 17 December 2013

Tom Shippey in The Road to Middle-earth (pgs. 238 & 239), 2003 has deduced that Tolkien knew and employed elements of the Early South English Legendary in his mythology.

3 Christopher Gilson and Patrick Wynne make the following comment in Parma Eldalamberon XIV on Tolkien’s The Creatures of the Earth of the early 1920’s:

“Tolkien’s elemental fays may owe something to the four varieties of elemental “spirit-men” described by Paracelsus: …”.

– The Creatures of the Earth, J.R.R. Tolkien, see Parma Eldalamberon XIV

4 It is quite possible that ‘Oaritsi’ which mermaids were first designated under (see The Book of Lost Tales I), was simply a sub-classification* of ‘Oarni’ – classified as ‘spirits of the sea’. The Oarni were, per early mythology, divine in originating before the creation of the World. Mermaids, we must note, were also equated as Oarni in The Book of Lost Tales II.

* Hence Oaritsi appearing in parentheses next to Oarni in The Creatures of the Earth, per Parma Eldalamberon XIV.

5 ‘Fays’ – what we might interpret as ‘fairy-folk’. For Tolkien, creatures of a divine nature originating outside of the Universe. Yet once inside and clothed in the raiment of Arda, and then having reproduced, progeny being termed ‘semi-divine’ is descriptively apt. It is quite probable that some fays were viewed by Tolkien as equivalent to ‘nature spirits’, though he never explicitly used that term.

6 The giants of the Misty Mountains (also known as stone-giants) per The Hobbit probably possessed linkage to this hierarchical classification document and category. Tolkien’s source* underpinning his own mythology is likely to have been an Edward Knatchbull-Hugessen publication of 1875: River Legends or Father Thames and Father Rhine and the tale of The Giant Bramble-Buffer. There are glaring similarities and strong resonances when comparing descriptions.

————

From The Hobbit, Chapter IV:

“… the stone-giants were out, and were hurling rocks at one another for a game, and catching them, and tossing them … They could hear the giants guffawing and shouting all over the mountainsides. … ‘… we shall be picked up by some giant and kicked sky-high for a football.’ ”. (my emphasis)

From River Legends:

The alpine giants of interest would:

“ ‘… fling enormous stones at each other in sport, which was pastime anything but delightful to their neighbours, whose lives and property were thereby grievously imperilled. …’ ”. (my emphasis)

They were described as highly vocal ‘Daddyroarers’:

“ ‘…‘roarer’ is … intended to convey, … the gruff and deep-toned voice which usually characterizes the giant …’ … ‘… roaming far and wide over the mountains … loud cries and roars were often heard for miles, …’ ”. (my emphasis)

While one particular mountain giant, Bramble-Buffer:

“ ‘… if he met a man he generally gave him a kick, which sent him off fifty yards up in the air, and in most instances proved fatal. …’ ”. (my emphasis)

————

Certainly such creatures were to be avoided at all costs. As related in Knatchbull-Hugessen’s story, and echoed by a chapter title in The Hobbit, getting too close could end up as a case of:

“… out of the frying-pan into the fire.”

However, by the end of the story Bramble-Buffer becomes a reformed character, echoing Gandalf’s words in The Hobbit, Chapter VI where it was conveyed that not all giants were bad, and his hope of finding:

“ ‘… a more or less decent giant …’ ”.

Extract from ‘River Legends’ by Edward Knatchbull-Hugessen, Illustrator Gustave Doré, 1875

As the picture above depicts, these legendary giants occupied themselves through mountain-building. One could infer then, that Tolkien’s stone-giants made use of stone and were not necessarily made of stone**.

Another relevant observation is that Tolkien’s description of the Misty Mountains traversal and the ‘thunder-battle’ stems from a 1911 trip across some of the Alps in Switzerland. In Letter #306 (from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981), he related:

“The hobbit’s (Bilbo’s) journey from Rivendell to the other side of the Misty Mountains, … is based on my adventures in 1911 …”.

Getting more specific, he told us:

“The summer of that year had melted away much snow, and stones and boulders were exposed that (I suppose) were normally covered. The heat of the day continued the melting and we were alarmed to see many of them starting to roll down the slope at gathering speed: … just in front of me (an elderly schoolmistress) gave a sudden squeak and jumped forward as a large lump of rock shot between us.”

His adventurous account mirrors that in The Hobbit, Chapter IV:

“Boulders, too, at times came galloping down the mountain-sides, let loose by mid-day sun upon the snow, and passed among them (which was lucky), or over their heads (which was alarming).”

Now literary tales where giants inhabit mountains are rare. Even rarer is a setting in the Alps. The Giant Bramble-Buffer tale is portrayed as taking place near the sector of the Alps adjacent to the Alpine-Rhine valley. Notably from Knatchbull-Hugessen’s fairy-story, there are matters which ought to have stirred memories of the 1911 expedition, which then might have carried across to The Hobbit mythology:

“ ‘… in the old, old times, the men of Rhineland were grievously troubled with giants of different sorts and sizes. Tradition tells us that they all sprang from the mighty giant Senoj, who, … was born, … among the loftiest peaks of the Alps, … Certain it is that his descendants, if such they were, proved exceedingly troublesome to mankind … they took a fancy to snowball each other, which the survivors of them still practise, especially in some parts of Switzerland, where the avalanche, which occasionally overwhelms the unhappy traveller, although mistakenly attributed to natural causes is in reality nothing more than the fall of a larger snowball than usual, hurled by the mighty arm of one of those mountain giants. …’ ”. (my emphasis)

The last underlining resonates with the creative origin of the Carrock in The Hobbit, Queer Lodgings:

“… it, was a great rock, … a huge piece cast miles … by some giant among giants.”

So large a chunk, if thrown, could only have been handled by a truly colossal giant; a giant much larger than we find, for example, in English lore. Furthermore, the Carrock lay within a river, thus matching the River Legends account where the giant Bramble-buffer hated the river Rhine of the tale:

“ ‘… and used to vary his occupations sometimes by pitching pieces of mountain into it, …’ “.

‘The Father of all Giants’ from River Legends by Edward Knatchbull-Hugessen,

Illustrator Gustave Doré, 1875

(indeed Senoj is a giant among giants!)

Therefore, it may be deduced that the upper reaches of the ‘Great River of Wilderland’ of The Hobbit (aka the Anduin per The Lord of the Rings) identify with the Rhine of Europe. While the Carrock is based on Lorelei Rock around which the Rhine looped, and Tolkien voyaged past in 1911. Topographically the Alps/Rhine/Lorelei Rock/Black Forest would then correspond to the Misty Mountains/Anduin/Carrock/Mirkwood of Tolkien’s conceit.

Vintage painting of Lorelei Rock, Artist and date unknown

Moving on to The Lord of the Rings (Book 2, Chapter 3), one must note that Clyde Kilby, a direct aide and friend to Tolkien, quoted:

“The storms in The Hobbit and at Caradhras in the Ring are modeled after Tolkien’s experience in the Swiss Alps in 1911 …”.

– Tolkien As Scholar and Artist, C.S. Kilby, The Tolkien Journal, Volume 3 Issue 1, 15 January 1967

Given a paired affinity, it is possible that the attempt to cross over Caradhras in The Fellowship of the Ring was foiled by an unseen stone-giant. The “shrill cries, and wild howls of laughter” are never pinpointed. Nor are the origin of the stones “whistling over their heads, or crashing on the path beside them”, or more significantly the ‘great’ boulder which “rolled down from hidden heights above them”. The final fall of “stones and slithering snow” is perhaps an allusive referral to the mythological avalanche caused by a giant’s throwing of a snowball as Knatchbull-Hugessen described above. And as to the name ‘Caradhras’ (one of three peaks below which Khazad-dûm lay), it translates across ‘Red horn’ which bears a fractured echo to the fairy tale: The Red Etin – about a cruel three-headed giant, and his horned monsters (see The Blue Fairy Book by Andrew Lang).

When it comes to authors, certainly Knatchbull-Hugessen was one Tolkien had encountered during his youth (Puss-cat Mew in Stories for My Children, 1869 was acknowledged – see Letter #319 from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 and accompanying footnote). His declared fondness for Puss-cat Mew is reason enough for him to have sought other fairy tales by this author. However, though Knatchbull-Hugessen was clearly a writer Tolkien favored, no record exists of a familiarity with River Legends.

* Michael Drout in J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment (pg. 478) offers up the possibility Tolkien’s stone-giants stem from the Eddic poem Grottasöngr. This could have been a source – though the evidence is decidedly weak. The Grottasöngr translation by Guðbrandur Vigfússon & F. York Powell in Corpus Poeticum Boreale (Volume 1, pg. 186) has two ‘giant maidens’ hurling rocks ‘below’ ground causing earthquakes (not ‘above’ causing carnage such as avalanches):

“We two playmates were brought up under the earth for nine winters. We busied ourselves with mighty feats; we hurled the cleft rocks out of their places, we rolled the boulders over the giants’ court, so that the earth shook withal.”

‘Giantesses Fenja and Menja’, Fredrik Sander’s 1893 edition of the Poetic Edda,

Illustration by Carl Larsson and Gunnar Forssell, 1886

(Courtesy of Wikipedia)

The proposal by Douglas Anderson of the stone-giants stemming from the gnome Rübezahl in Andrew Lang’s The Brown Fairy Book, 1904 (see John Rateliff’s The History of the Hobbit) appears tenuous. Especially in light of the newly unearthed River Legends material.

At least one notable authority in Tolkien scholarship has hinted that the stone-giants might have been allegorical and represented natural storm phenomena. Although their textual specificity within The Hobbit makes that unlikely (particularly for a children’s fairy tale), until this article no compelling mythological antecedent for mountain-inhabiting stone-giants had been uncovered.

** Although the correlation isn’t exact, this would align with his Letter #324 remarks where he clarifies the Gondorians – people of ‘Stone-land’, were not composed of stone but built with them.

7 Pygmies here, were likely thought of in the context of being mythological creatures, for they are indeed a term employed by Paracelsus for an elemental of the earth. This view is shared by Patrick Wynne and Christopher Gilson:

“… ‘pygmies’ were probably intended as beings akin to the earth-elementals of Paracelsus …”.

– The Creatures of the Earth, J.R.R. Tolkien, see Parma Eldalamberon XIV

Tolkien was clearly aware of Paracelsus’ invention as pointed out in a footnote to Letter #239 (from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981) when comparing ‘gnome’ and ‘pygmaeus’:

“… the word gnome used by the 16th-century writer Paracelsus as a synonym of pygmaeus. Paracelsus ‘says that the beings so called have the earth as their element …’ ”.

It is theorized that Tolkien set apart ‘Earthlings’ from the category of ‘Monsters’ due to the former inherently possessing moralistic free will. In other words ‘Earthlings’ were capable of being both evil and good. This seems to be have been reflected in both the Bramble-buffer tale in River Legends per “The race of giants are a curious combination of good and evil”, and The Hobbit – where in the journey over the Misty Mountains, Gandalf aired a desire to find “a more or less decent giant”. A ‘mountainous-giant’ under the category of ‘Earthlings’ might well have been what Tolkien had in mind.

In any event, the fact that the group designated ‘Earthlings’ in The Creatures of the Earth appears to contain one Paracelsian-type elemental, makes one wonder whether other creatures of that lore were deliberated to belong too. It is conjectured that water-nymphs, mermaids and undine-like entities, were also considered to – if not wholly belong – at least overlap into that same mythological grouping.

8 Before The Lord of the Rings, dwarves at one time were also considered to be elemental entities. In The Later Annals of Beleriand (The Lost Road and Other Writings, pg. 129):

“… Dwarves have no spirit indwelling, … and they go back into the stone of the mountains of which they were made.”

It should be noted The Creatures of the Earth preceded The Later Annals of Beleriand. Thus, it maybe concluded, dwarves were categorized as soulless creatures in this earlier document.

9 Tolkien stated that the spirit had become “imprisoned” in the Great Willow. The implication being that the tree was not its natural habitat. This is aligned with poetry where the tree is considered to be separate from the entity:

“ ‘Ha, Tom Bombadil! What be you a-thinking,

peeping inside my tree, watching me a-drinking

deep in my wooden house, tickling me with feather,

dripping wet down my face like a rainy weather?’ ”

– The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, 1934 (& 1962) poem (my emphasis)

10 Tolkien’s pronouncement about ‘souls’ is implied as applicable to all types of Troll. The comment in Letter #153 (from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981) of Trolls being “counterfeits” refers to the Dark Powers only possessing the ability to corrupt, and not truly create life; thus reflected (for the Stone-trolls) in an unstable design destructible by sunlight.

11 Tolkien placed Trolls under ‘Úvanimor/Monsters’ in The Creatures of the Earth (see Parma Eldalamberon XIV, by Patrick Wynne, Arden Smith & Christopher Gilson). These being life-forms classifiable as wholly evil in nature:

“… I do not agree … that my trolls show any sign of ‘good’, strictly and unsentimentally viewed.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #153 – September 1954, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (Tolkien’s emphasis)

12 Best thought of as equivalent to the ‘Flame Imperishable/Secret Fire’ in Tolkien’s mythology, perhaps. Particularly as Vulcan (from which Vulcanus is derived) was the Greek god of fire, and the soul is classically referred to as the internal ‘spark of life’.

13 Paracelsus described the ‘flesh’ of elementals as transubstantial. Not directly derived from Adam – this flesh (unlike the corporeal kind endowed to mankind) could revert to its basic constituent form. In taking such an idea, Tolkien certainly followed Scandinavian folklore and early pagan thinking when it came to The Hobbit. Trolls therein were essentially portrayed as elementals of the earth, vulnerable to instantaneous petrification if not under it while the sun visibly shone:

“Doubtless ancient pre-Christian imagination vaguely recognized differences of ‘materiality’ between the solidly physical monsters, conceived as made of the earth and rock (to which the light of the sun might return them), …”.

– Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics, Sir Israel Gollancz Memorial Lecture, 1936 (Tolkien’s emphasis)

14 One can imagine a spirited discussion having taken place with Tolkien on such a matter. C.S. Lewis, after all, was a lover of mythology and fairy tales too. Certainly he had become acquainted with Arthur Rackham’s Undine; and as early as 1916. We also know that he had read Robert Browning’s Paracelsus by 1918 and it would not be at all surprising if in this same time-frame he familiarized himself with the original source of undine mythology, Paracelsus’ Liber de nymphis, sylphis, pygmaeis et salamandris et de caeteris spiritibus (of 1515). In 1949 he related he had already read this work – although he didn’t pinpoint exactly when. It must have been before 1946 when Lewis read a new poem on Paracelsus’ view of gnomes, thought to be The True Nature of Gnomes – at an Inklings meeting.

Though Lewis demonstrably showed much interest in Paracelsus’ elementals, Tolkien – in criticizing The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, obviously claimed superior knowledge on the branch of mythology germane to nymphs:

“ ‘It really won’t do, you know! I mean to say: ‘Nymphs and their Ways, The Love-Life of a Faun.’ Doesn’t he know what he’s talking about?’ ”

– C.S. Lewis: A Biography, pg. 241, R.L. Green/W. Hooper, 1974 (my emphasis)

15 Stated as the ‘salamanders’ amid flames, ‘gnomes’ of the earth, forest ‘spirits’ of the ‘air’ and the race of ‘water spirits’. All of these elementals are perfectly aligned with earlier Paracelsian mythology.

It is probable that as well as mermaids and undines, the race of soulless water-spirits included the closely related Scandinavian/Germanic neck, nickar, nicor, nixie or nokken. The male nickar was versified by Sebastian Evans (Macmillan’s Magazine, Nickar the Soulless, Vol. 9 Iss. 49, Nov 1863) as ‘soulless’ thus:

Where by the marishes

Boometh the bittern,

Nickar the soulless One

Sits with his ghittern:-

Sits inconsolable,

Friendless and foeless,

Wailing his destiny,

Nickar the soulless.

‘Nøkken’, Illustration by Theodor Kittelsen, 1904

(note the presence of water-lilies)

16 Paracelsus’ elementals were generally invisible to mortals.

17 In classical 16th Century English poetry, Michael Drayton’s Poly-Olbion allegorically describes the marriage of the rivers Thame and Isis, from whose union is born the Thames:

“Now Fame had through this Isle divulged in every ear

The long expected day of marriage to be near,

That Isis, Cotswold’s heir, long woo’d was lastly won,

And instantly should wed with Thame, old Chiltern’s son.”

In Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, the Isis is the female partner, and she is a “weak and crooked creature” requiring the support of her attendants – the rivers Churne and Cherwell. These are both feminine. Thus, it is no surprise that the Cherwell is assigned a water-nymph in Drayton’s Poly-Olbion, while the Isis is depicted as more senior (see zoom frames below taken from Poly-Olbion view in body of article). So in effect there is a tradition within English mythology of rivers possessing mother, father and younger water-spirits.

Tolkien studied both Drayton and Spenser as part of his undergraduate course material at the University of Oxford. Later on it appears he took an interest in the etymology of ‘Thame’ per his amusing fairy tale Farmer Giles of Ham – except he gave his own spin (derived from ‘Ham’ and ‘Tame’ – and Tame, one might note, is the river’s name on this Poly-Olbion map). Assigned to a mythical period a thousand years earlier than Drayton’s poetry, the story was set in the valley of the Thames.

Tolkien proffered up a “true explanation of the names” in that tale – perhaps hinting that predecessors had got their analytical derivations wrong. Hence, we have a tenuous link that Tolkien indeed knew of Drayton’s Poly-Olbion. If so, it would have been natural for him to review the river maps of Oxfordshire. In which case he might have concluded, that from a mythological standpoint, water-nymphs are not out of place as river-residents in a region meant to mimic Oxfordshire in an epoch long ago.

18 Reminiscent of the sighs expressed by the Withywindle River-woman.

19 Tolkien titled his Elves the:

“Fair Folk. The beautiful people (based on Welsh Tylwyth teg ‘the beautiful kindred’ = fairies). Title of the Elves.”,

– Nomenclature of the Lord of the Rings, Names of Persons or Peoples, J.R.R. Tolkien

and not the Sidhe (Tuatha de Dannan) of Ireland as some have suggested. Neither were his noble race representative of the creatures told about in household tales common across European folklore:

“The Elves of the ‘mythology’ of The Lord of the Rings are not actually equatable with the folklore traditions about ‘fairies’, …”.

– Nomenclature of the Lord of the Rings, Names of Persons or Peoples, J.R.R. Tolkien

20 Tolkien proclaimed The Lord of the Rings story (excluding appendices and maps) as finished in December 1949 (Letter #122 from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981). It was then set aside for essentially three years before earnest interest in publication re-arose. There is no evidence that ‘fays’ as a mythological entity grouping was superseded (or discarded as obsolete) before 1949. In the early 1950’s evidence exists in Morgoth’s Ring that Tolkien absorbed some fays into a newly named mythological class termed ‘Maiar’; again creatures of divine status. Yet it cannot be proven that this occurred across the board.

As far as The Lord of the Rings, ‘fays’ are the valid default. Especially as Goldberry’s genera ought to have been established back in 1938 at the first point of her being firmly cast into the mythology. Moreover, it can be proven that in 1939 ‘fays’ was terminology still very much in use:

“Faërie contains many things besides elves and fays, and besides dwarfs, witches, trolls, giants, or dragons: …”.

– The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, On Fairy-stories – pg. 113, HarperCollins, 1983 (my emphasis)

As far as the ‘Maiar’ (helpers of the Valar) – this term could be viewed as a general grouping encompassing a wide variety of mythological entities. However, even if so, it is still possible Tolkien preferred to keep sub-categorization of some of these creatures into different kinds of ‘fays’. Particularly as he declined to update The Creatures of the Earth.

We must also note that Tolkien did not explain the Istari using the words ‘Maia’ or ‘Maiar’ in the Appendices of the 1955 released The Return of the King – though he had the opportunity to do so. Neither was such vocabulary used in any writings authorized for publication by the Professor himself post The Lord of the Rings. Whereas the term ‘fay’ was not completely discarded – appearing twice in Smith of Wootton Major released in 1967.

21 The four types of water-fay listed/glossed in Parma Eldalamberon XIV under The Creatures of the Earth are: ‘nenuvar’: fays of lily-ponds; ‘aïlior’: fays of lakes and pools; ‘ekterlarni’: fays of fountains & ‘capalini’: fays of springs. Chronologically, in Tolkien’s creation of the Qenya vocabulary, they supersede the ‘waterfay’ entity category termed ‘nendil’ or ‘nennil’ in The Grammar and Lexicon of the Gnomish Tongue (see Parma Eldalamberon XI, by Patrick Wynne, Arden Smith & Christopher Gilson).

Although the word ‘nindaríli’ – glossed as ‘river-maid’ or ‘nymph’ – appears in The New Q(u)enya Lexicon (see Parma Eldalamberon XXI, by Patrick Wynne, Arden Smith & Christopher Gilson), which was produced after The Creatures of the Earth, these glosses are unlikely to refer to a racial entity-category. Rather, they may be deemed as more casual terms of address for such a creature as Goldberry:

“… He sang like a starling,

hummed like a honey-bee, lilted to the fiddle,

clasping his river-maid round her slender middle.”

– The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, 1934 (& 1962) poem (my emphasis)

For example a woman may be termed a lady, girl, maid, etc. – but technically, in terms of race, she is of ‘human’ kind.

22 Despite nearly two decades having passed between the production of The Creatures of the Earth and the inception of The Lord of the Rings, no records exist in this time-span of any alternate categories of ‘inland’ water-fays, or humanoid water-beings.

Necessarily then, Tolkien must have envisaged Goldberry (and presumably Tom) to have been loosely connected to a developing mythology in 1934 – having then released The Adventures of Tom Bombadil.

23 Christopher Gilson and Patrick Wynne note that ‘nénuvar’ with a diacritic mark defines ‘pool of lilies’.

24 See Angel and Demon, Gospel and Fairy-story Part II.

25 See Angel and Demon, Gospel and Fairy-story Part III.

26 See The Last Stage – Part II.

Revisions:

Grammatical, spelling and minor error corrections are not recorded. Neither are minor changes to phrasing that have little bearing as to the thrust of the message being conveyed by the author.

All revisions prior to 2020 are archived. Please contact the author if records are required.

2/10/20 Added: “– except he gave his own spin”.

2/18/20 Added: “for mankind”.

Added: “causing earthquakes (not avalanches)”.

Added: “Tolkien proffered up … analytical derivations wrong.”.

3/4/20 Added: “raised in a society where ‘sex’ was practically a taboo subject”.

4/17/20 Added: “Yet despite all of the analysis … see Parma Eldalamberon XIV”.

Added new footnotes 3, 18, 19 & 20, reordered others.

5/4/20 Added: “* Hence Oaritsi appearing in parentheses next to Oarni in The Creatures of the Earth, per Parma Eldalamberon XIV.”.

Is: “ ‘Fays’ – what we might interpret as ‘fairy-folk’. For Tolkien, creatures of a divine nature …”, Was: “ ‘Fays’ – usage probably as in the sense of ‘fairy-folk’. Again, creatures of a divine nature …”.

Added: “… ‘pygmies’ were probably intended … – The Creatures of the Earth, J.R.R. Tolkien, Parma Eldalamberon XIV”.

6/1/20 Added: “Even though the following statement … beginning in 1938:”.

Added Letter #309 quote.

Added: “and the ‘thunder-battle’ ”.

7/13/20 Added: “But perhaps she wasn’t permanently locked in and possessed the ability to survive for short periods adjacent to the water.”.

Added: “Yet once inside and clothed in the raiment of Arda, being termed ‘semi-divine’ is descriptively apt.”.

Added: “Yet it cannot be proven … appearing twice in Smith of Wootton Major released in 1967.

7/21/20 Added quote from The Adventures of Tom Bombadil: “… He sang like a starling, … slender middle.”.

Added new footnote 14, reordered others.

8/5/20 Added picture extract from Poly-Olbion.

9/2/20 Added: “Particularly as Vulcan … the ‘spark of life’.”.

9/24/20 Removed: “The river itself must have been there before Goldberry and hence is the elder of the two. Goldberry simply became attached to it some time after its formation. If that was the case, then most sensibly she can be termed its ‘daughter’.”.

Added picture of ‘The Great Chain of Being’.

Added: “Now literary tales where giants inhabit mountains are rare.”.

10/10/20 Added: “This is aligned with poetry where the tree is considered to be separate from the entity:”.

Added quote from The Adventures of Tom Bombadil to footnote 9.

11/28/20 Removed: “Therefore it effectively acted maternally in the sense of being a provider and source of comfort.”.

12/06/20 Added: “Echoed by our understanding of … J.R. Clark Hall, 1894”.

Added zoom-shot of embodied ‘Isis’ to footnote 17.

2/18/21 Added: “Even rarer is a setting in the Alps.”.

Added: “His declared fondness for Puss-cat Mew is reason enough for him to seek out other fairy tales by this author.”.

3/14/21 Added: “, vulnerable to instantaneous petrification if not under it”.

4/12/21 Added: “Certainly such creatures were to be avoided … end up as a case of:”.

Added quote: “… out of the frying-pan into the fire.”.

Added: “Furthermore the Carrock was besides … hated the river of the tale:”.

Added quote: “… and used to vary his occupations sometimes by pitching pieces of mountain into it.”

Added: “both the Bramble-Buffer tale in River Legends per “The race of giants are a curious combination of good and evil”, and”.

10/17/21 Added: “Therefore it might be deduced that the ‘Great River of Wilderland’ … Misty Mountains/Anduin/Mirkwood of Tolkien’s conceit.”.

11/9/21 Added: “One must conclude then, that Tolkien’s stone-giants … stone but built with them.”.

11/17/21 Added: “Necessarily then, Tolkien must have envisaged Goldberry (and Tom) to have been connected to the mythology in 1934 – having then released The Adventures of Tom Bombadil.”.

12/15/21 Added: “Yet how can we fault him for not anticipating or catering to our more liberal world of the 21st Century?”.

Was: “Naturally one might deduce that this magical internal energy we humans were so lucky to have, was not just the ability to reason – but our gifted ‘souls’. Evidently Tolkien disagreed – at least with the ability to talk being the divide:”, Is: “That magical internal energy we humans were so lucky to have, allowing us to use complex reasoning via language, was down to our gifted ‘souls’. But just because beasts and monsters in fairy tales could communicate employing equally sophisticated speech – didn’t mean they too were endowed with souls. So Tolkien disagreed with the ability to talk being a divide:”.

2/24/22 Is: “sightings of Goldberry’s mother were not commonplace”, Was: “the mother or mother-in-law situation was not an issue to Tolkien”.

Added: “So large a chunk, if thrown, could only have been handled by a truly colossal giant; a giant much larger than we find, for example, in English lore.”.

Added: “- and Tame, one might note, is the river’s name on this Poly-Olbion map”.

Added: “, or humanoid water-beings.”.

5/28/22 Added: “and then having reproduced, progeny”.

Added: “While the Carrock was based … voyaged past in 1911.”.

Added picture of Lorelei Rock.

6/17/22 Added: “Through the ages much confusion … the possibility of Goldberry being a fay?”.

Added new footnote 19, reordered existing.

7/1/22 Added: “Even in Tolkien’s last writings … next to a ‘lily-pool’:”.

Added lines from poem Once Upon a Time.

8/15/22 Removed all section breaks: “*****”. Added sub-section titles, 3 places.

Added: “It should be noted The Creatures of the Earth preceded … this earlier document.”.

10/11/22 Added: “And so ingeniously the idea developed to make his great fairy story their ultimate source. To strengthen such a postulation, I have had to dig deep and ponder upon the roots of European mythologies. For”.

Added: “They were described as highly vocal … While”.

11/29/22 Added sub-section titles: Understanding Goldberry’s Genus: A Way Forward, Earthlings in The Lord of the Rings, Withywindle Women and their Mythological Makeup.

2/26/22 Added: “one must note that Clyde Kilby, a direct aide and friend to Tolkien, quoted: … Given a paired affinity”.

One thought on “Goldberry: The Enigmatic Mrs Bombadil”

Comments are closed.