Part IV – The Watcher of the World Play

.

Making Sense of the Creator’s Plan

Mainly missing from the analytical treatment so far is a healthy dose of good old-fashioned ‘philosophy’. It’s not just a necessary tonic, but a vital part of the medicine. Because from Tolkien’s profoundly erudite views we can extrapolate, in a logical manner, and thus grasp the simplicity of the structural setup behind his mythological world. In turn, such philosophical discussion will yield rewards. For it will lead back to Bombadil and reinforce his role in the whole affair. If all the administered therapy through the previous 27 articles has been dutifully digested, with one last push the ailment that afflicts the curious can be completely cured. That maddening ‘ache’ left behind in the hearts of those dissatisfied with Tolkien’s tale can be remedied. Yes, lasting relief is at hand for a legion of troubled readers – unhappy, unwilling or unable to let Bombadil go.

So onward to philosophizing over that quartet of age-old ideological enigmas:

‘What is the meaning of life?’

‘Why are we here? Who put us here? And where are we going?’

Ah yes … those great mysteries of our existence! Those perplexing questions mankind has sought solutions to since the dawn of consciousness. Indeed, ever since the realization that our place on the planet is unique, few have escaped from pondering on such matters – and least of all Tolkien.

.

.

Despite the tragedies inflicted in childhood with the early death of his parents, and then as a young adult, from the untimely loss of several of his closest friends in war – it was religion that kept Tolkien going. For strangely enough it was faith that enabled him to rationalize heart-rendering bereavements and come to a personal acceptance of his position within the ordained hierarchy of the Universe. Religion was key to it all. A man’s place on the planet, along with all the accompanying sorrow and joy during life, could be reconciled by first believing in a Christian God – and then through submission to His will.

Tolkien was once asked that most difficult of questions by a young child:

“What is the purpose of life?”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #310 – 20 May 1969, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

His answer provides some noteworthy insight regarding his thought process. Quickly and adeptly he managed to swing the subject round to pondering upon the existence of God:

“ ‘Why did life, the community of living things, appear in the physical Universe?’ introduces the Question: Is there a God, a Creator-Designer, a Mind to which our minds are akin (being derived from it) so that It is intelligible to us in part.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #310 – 20 May 1969, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

For the Professor God was undeniable; the evidence lay before humanity’s eyes. For in nature everything before us was ‘other’:

“… we did not make them, and they seem to proceed from a fountain of invention incalculably richer than our own.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #310 – 20 May 1969, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

Then if ‘everything’ resulted from a supreme inventor possessing incalculable knowledge and incredible power, His motive should not be questioned:

“If we ask why God included us in his Design, we can really say no more than because He Did.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #310 – 20 May 1969, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

So if we logically extend this a little further, we can reasonably deduce that for Tolkien, all creation happened because of God. The inhabitants of Earth; the great celestial objects in the sky – Sun, Moon, planets and faraway stars; indeed the very Universe – were all due to God’s will. Globed within undetectable boundaries all matter, as we know it, was subject to the irreversible passage of Time. This was the seen world, but there were also unseen ones – comprising for his faith: ‘Heaven’ and ‘Hell’. And they did not exist within the same confine.

So just as mankind has never been able to crack, with definitive proof, the enigmas resulting from our existence – nor confirm the inhabited presence of ‘other worlds’, it was easier to bypass it all and just accept we are here on this lonely planet because of God’s ‘plan’. To accept our uniqueness and mortality, and to some degree – where our fates led, was really the only logical choice. It was not the part of a good Christian to question God’s intentions. Yet certainly a far superior intelligence must have had a purpose.

Now when it comes down to it, I think the easiest way for Tolkien to intellectualize God’s master plan was to conceptualize it as His great ‘play’. There was a script, that He the Author had ‘written’ – with both a beginning and an end. We humans were the primary ‘actors’ on the ‘stage’. Gifted with a large degree of ‘free will’ we are thus able to shape, within limitations, our destinies and the outcome of ‘history’. This was God’s great Drama – the history of the world. And He was interested in every bit of it.

St. Thomas Aquinas – philosophized the reason for our existence is God

.

Of course my thoughts are a guess; Tolkien never explicitly stated so. Nevertheless, I feel it’s a reasonable presumption because in the act of subcreating his own myth, Tolkien used very much the same concept. However, he added his own twist by splitting the drama up into two halves. The main performance of the Ages comprising Time within the Universe was preceded by:

“… a cosmogonical myth: The Music of the Ainur …”.

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #131 – late 1951, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981

Before the act of our world’s creation much of the plot had been shown, like a ‘rehearsal’, to the Ainur in vision form:

“Their power and wisdom is derived from their Knowledge of the cosmogonical drama, which they perceived first as a drama (that is as in a fashion we perceive a story composed by some-one else), and later as a ‘reality’.”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #131 – late 1951, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (my underlined emphasis)

This gathering by Ilúvatar of his angelic offspring, The Music and the vision revelation were all parts of the ‘Creation Drama’, however for the Ainur:

“The Knowledge of the Creation Drama was incomplete: …”.

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #131 – late 1951, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (my emphasis)

Certain elements in the rehearsal had been intentionally left out awaiting those of the enamored Ainur to discover for themselves.

Out of all this we most note how repeatedly the term ‘drama’ was employed. Whether for the earlier portion of the story Outside: the ‘Creation Drama’ (also termed the ‘cosmogonical drama’), or after the genesis of the new world: the ‘Drama’1 played out in Time – the message is that Tolkien points to the overall story acted out as a ‘rehearsal’ and then a proper ‘play.’ In itself this is a very simple idea and one we can all readily understand.

If Tolkien really thought that way, then we must look for further confirmation. By inferential extension if indeed he imagined his entire mythological story as a ‘drama’ then there ought to be hints of a ‘theater’ and a ‘stage’ with ‘actors’ and a ‘scriptwriter’ etc. Tolkien ought to have left some other clues. Fortunately, numerous comments in texts and correspondences provide evidence aplenty:

From The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 with my underlined emphasis:

“… the actors are individuals …” – Letter #109

“… the intrusions of the Children of God into the Drama …” – Letter #131

“… Men do not come on the stage …” – Letter #131

“The theatre of my tale is this earth, …” – Letter #183

“… the whole great drama both of history and legend …” – Letter #205

“The Fall of Man is in the past and off stage; …” – Letter #297

From various chapter’s of Morgoth’s Ring, 1993 again with my underlined emphasis:

“The Great Music, which was as it were a rehearsal …”

“… God’s management of the Drama …”

“… the principal Drama of Creation …”

“… the Drama by Eru …”

“… the Valar who were to be actors.”

“… the Drama of Arda is unique.”

“… presented as visible drama to the Ainur.”

Even more clearly, the arrangement is openly conveyed by the ‘wise’:

“… Eru could not enter wholly into the world and its history, which is, however great, only a finite Drama. He must as Author always remain ‘outside’ the Drama, even though that Drama depends on His design and His will for its beginning and continuance, in every detail and moment.”

– The History of Middle-earth, Morgoth’s Ring, Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth – pg. 335, 1993 (my underlined emphasis)

How can we possibly issue a denial when its spelled out in such a clean-cut manner? I’m not about to debate the finer nuances or exactness of Tolkien’s comments – but essentially my views have not changed from those laid down in my very first article. In Tolkien’s mind the bounded Universe could be likened to a ‘theater’ with the ‘stage’ being our planet in which his mythical drama involving Men and Elves (the Children of God) would be played out. As scriptwriter for his ‘play’, in effectively the same role as God, this was reason enough for remaining on the sidelines:

“… I do not really belong inside my invented history; and do not wish to!”

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #309 – 2 January 1969, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (Tolkien’s italicized emphasis on ‘inside’)

Nor was Tolkien alone in such thoughts among his compatriots. C.S. Lewis (Mere Christianity, The Practical Conclusion – pg. 65, 2001 Edition) too wondered:

“… whether people who ask God to interfere openly and directly in our world quite realise what it will be like when He does.”

Because according to his belief:

“When that happens, it is the end of the world.”

And just like Tolkien – he used theatrical terminology to make his point:

“When the author walks on the stage, the play is over.”

.

Conceptualizing the Plan

By now readers might be scratching their heads. Or perhaps that light bulb has finally gone on? Perhaps some have already made the next connection given the vast emphasis I’ve placed in previous articles on the importance of period plays to the Mythology’s roots. Yes, by no means was Tolkien’s idea unique. It had already been thought out and expressed by the Elizabethans in English Renaissance drama.

.

Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre (2nd construction), ‘Hollar’s View of London’, 1647

.

One of Shakespeare’s most famous dialogues was:

“All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players; …”.

– As You Like It, Act II-Scene VII, W. Shakespeare, c. 1599

Similarly, in another play:

“I hold the world, but as the world, Gratiano; A stage where every man must play a part, …”.

– The Merchant of Venice, Act I-Scene I, W. Shakespeare, c. 1596-1599

Even better put were words by Thomas Heywood echoed by those of Thomas Middleton:

“The world’s a Theater, the earth a Stage, Which God and Nature doth with Actors fill, …”.

– Prefix to An Apology for Actors, T. Heywood, 1612

“The world’s a stage on which all parts are played.”

– A Game of Chess, Act V-Scene I, T. Middleton, 1624

Hmm … so far things tie in with all that was stated so long ago. My postulation, however, is that Tolkien took the idea one step further than anyone else had done. If a solely literary performance his magnum opus was to be – then a permanent audience would still be necessary to ‘watch history’, even if it were feigned. Otherwise, any acting on the ‘literary stage’ would end up being fundamentally no more than another ‘rehearsal’ – in effect his written novel would be analogous to a ‘proof copy’. Such a seemingly minor detail was a quirky sticking point that could not be overcome. His book-form tale would still need a dedicated onlooker from beginning to end.

In encumbering himself with a rather eccentric self-stipulation, as I stated in my very first article, Tolkien found a purpose for a very special character. Cast in a dramatic story – Tom Bombadil was destined to be conferred an idiosyncratic role. It was he that would be the much-needed representation of the ‘audience’. How do we know? Well, almost given away in Tolkien’s correspondence with a close friend were traceable clues from which we can reasonably guess the Professor’s intent:

“ ‘ … This is like a ‘play’ … there are noises that do not belong, chinks in the scenery’, discussing in particular the status of Tom Bombadil in this respect.”

– Letter from Tolkien to P. Mroczkowski, 20-26 January 1964, Auction contents, Christie’s Fine Printed Books and Manuscripts, 1 June 2009 (my underlined emphasis)

Why is this like a play? – We’ve had enough discussion on that already!

Whose noise doesn’t belong? – Bombadil’s of course!

What are the chinks in the scenery? – Glimpses of another world off stage, the tandem ‘auditorium’!

Yes, if Tolkien himself used a theatrical analogy and then (as discussed in Tom Bombadil: Cracking The ‘Enigma’ Code – Part I) extended it to tell us the world outside contained “the producer, stagehands and the author”, then why can’t Tom allegorically be thought of as the ‘audience’? Especially when the Professor told us that (just like any audience member) Tom is “outside the problems of power that involve the other characters” in not belonging to “the main pattern of the Legendarium”.

.

The Earth’s a Stage when viewed from an Auditorium!

.

Now we must not be fooled by the hostility the Professor displayed towards man-made theater-drama on several occasions:

“The radical distinction between all art (including drama) that offers a visible presentation and true literature is that it imposes one visible form. Literature works from mind to mind and is thus more progenitive.”

– The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, On Fairy-stories, Note E – pg. 159, HarperCollins, 1983

“I think the book quite unsuitable for ‘dramatization’, …”.

– The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #175 – 30 November 1955, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 (Tolkien’s emphasis)

The comments above have nothing to do with the idea behind his mentally conceived great play. Indeed, there is no conflict because what Tolkien intimated is absolutely true when viewed in context. The traditional stage is unsuitable for depicting fantasy with a good measure of credence. It wasn’t back then, and it still isn’t now. Technology hasn’t advanced far enough to make a worthy dramatization of a story like The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings within the imposed limitations of a regular theater.

Nevertheless, when immersed in a mesmerizing performance, it is still possible to lose oneself at moments and become so engrossed – that one feels part of a secondary reality. A gifted artist, in small measure, could provide a “visible form” wholly agreeable with spectators. And I think this is what Tolkien himself experienced on occasions when enraptured in a live show. Without consciously being aware his mind was being manipulated by another person (namely the scriptwriter), it was only after the performance and due reflection that full realization of the effect dawned. It was this all too fleeting yet exhilarating experience that, I believe, led him to coin the term ‘Faerian Drama’, for which of course he had his own literary fantasy in mind:

“… ‘Faërian Drama’—those plays which … can produce Fantasy with a realism and immediacy beyond the compass of any human mechanism.”

– The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, On Fairy-stories – pg. 142, HarperCollins, 1983 (Tolkien’s emphasis)

If the story-maker is truly successful:

“He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is ‘true’: it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside.”

– The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, On Fairy-stories – pg. 132, HarperCollins, 1983 (Tolkien’s emphasis)

With Frodo, it was Tom Bombadil who projected and manipulated an induced vision of “a far green country”. Perhaps this is the clearest example of an actual application in the novel. If that is the case, then highly interesting is a logical presumption that Tom had the ability to not just see things far off, but become entwined with them in a ‘secondary reality’. It is because of this ability that my focus turns to a legendary Welsh figure seemingly endowed with a comparable skill.

The Great Welsh Watcher

Along with all the other pseudo alter-egos already discussed in prior articles – Tom, the bardic singer of his realm, shares traits with Taliesin – the great druid ‘Bard of the West’ from the Welsh Mabinogion tales Tolkien was quite familiar with. Taliesin means ‘shining brow’ and because of this he has loose linkage to the Celtic demigod Lugh2 – a sun god, and the Welsh deity Lleu3 – the ‘bright’ or ‘shining one’. Like no character in historical writings, and as Leslie Jones in Myth & Middle-earth has pointed out – Taliesin’s claims were extraordinary and resonate with Bombadil’s own4 amazing declarations:

“I was with my Lord in the highest sphere,

On the fall of Lucifer into the depth of hell:

I have borne a banner before Alexander;

I know the names of the stars from north to south;

I have been on the galaxy at the throne of the Distributor;

I was in Canaan when Absalom was slain;

I conveyed the Divine Spirit to the level of the vale of Hebron;

I was in the court of Don before the birth of Gwdion.

I was instructor to Eli and Enoc;

I have been winged by the genius of the splendid crosier;

I have been loquacious prior to being gifted with speech;

I was at the place of the crucifixion of the merciful Son of God;

I have been three periods in the prison of Arianrod;

I have been the chief director of the work of the tower of Nimrod;

I am a wonder whose origin is not known.

I have been in Asia with Noah in the ark,

I have seen the destruction of Sodom and Gomorra;

I have been in India when Roma was built,

I am now come here to the remnant of Troia.

I have been with my Lord in the manger of the ass:

I strengthened Moses through the water of Jordan;

I have been in the firmament with Mary Magdalene;

I have obtained the muse from the cauldron of Ceridwen;

I have been bard of the harp to Lleon of Lochlin.

I have been on the White Hill, in the court of Cynvelyn,

For a day and a year in stocks and fetters,

I have suffered hunger for the Son of the Virgin,

I have been fostered in the land of the Deity,

I have been teacher to all intelligences,

I am able to instruct the whole universe.

I shall be until the day of doom on the face of the earth;

And it is not known whether my body is flesh or fish.”

– The Mabinogion, Taliesin – pgs. 482-483, Lady Charlotte Guest Translation, 1877

Tolkien may well have been intrigued by this wondrous being “whose origin is not known”. But how were all these feats and claims possible? What purpose would have been served by witnessing such historic moments? And then what reason required a presence from beginning to end?

.

‘Taliesin and The Cauldron of Ceridwen’, The Mabinogion, Lady Charlotte Guest, 1877

.

Possible? Well yes – imaginably if one were divine. Or feasibly if one were present in spiritual form. Or maybe if one became engaged through the verisimilitude of a Faerian Drama! Then one could be witness. Then one could feel one was there; that is if the art form possessed “realism and immediacy beyond the compass of any human mechanism”!

But why would one want to?

Perhaps if one was designated a unique role! Perhaps if one were the ‘audience’ of God’s ‘play’!

Yet one boast might have puzzled the Professor exceedingly. How could anyone “instruct the whole Universe” unless that person was God Himself?

My feelings are that Tolkien thought of a way. And that was because he desired to provide yet another connection of Tom to the legends of the British Isles. So to extract that I have to turn back to Tom Bombadil: Cracking the ‘Enigma’ Code – Part II. Therein I hinted at Tom’s secondary role on the planet as the ‘Orchestra of the Play’. But that should get us thinking. What about Outside? What about before the creation of the Universe?

Before I speculate further, I need to turn back to Bombadil’s Sindarin name: Iarwain Ben-adar – construction which I have already stated – positively reeks of Celtic origination. Though I’ve already supplied an etymological possibility – room exists for other interpretations. It is intriguing that ‘Iarwain’ might have been rooted with the Middle Welsh words:

‘arwain’: first, a leader or conductor of music

‘awen’: poetic inspiration

Perhaps the Lady Guest translation of:

Bum yn arwain o flaen Alexanderm

which was given as:

I have borne a banner before Alexander

could equally be interpreted as:

‘I have led the music in front of Alexander’.

Hmm … that ought to further stimulate our synapses!

For the Creation Myth we know the choirs of the Ainur sang to Eru’s command. But who was the conductor of this ensemble? Who organized and directed them in singing the first theme of the Music? No, this wasn’t Eru’s role. His contribution can be likened to producing the major chords in creating the overall theme on the ‘music sheet’. It was the Ainur’s task to fill in the melodies, and it was for Eru to hearken and enjoy the performance.

Surely then there was a need for a conductor? Without one wouldn’t the Music have been chaotic? Surely Tolkien would have understood this important detail? Once again, who was the conductor of the orchestral choirs? Could Tom have been that spirit?

Having played his part in the creation portion of the drama ‘Outside’ – was he now destined to add to his ‘orchestral’ role and become the ‘audience’, for the World-based play of history, while retaining a trace of his allegorical role in name-form? Was a multifaceted Tom deliberately modeled to share traits with Taliesin? Is that how myth ended up as historic legend? Perhaps that amazing boast of being able to “instruct the whole Universe” had a grain of truth?

Who knows for certain? Again I admit, only Tolkien would have been able to tell us for sure whether Tom’s Sindarin title held another remarkable secret!

A Finishing Touch to a Bombadil Masterpiece

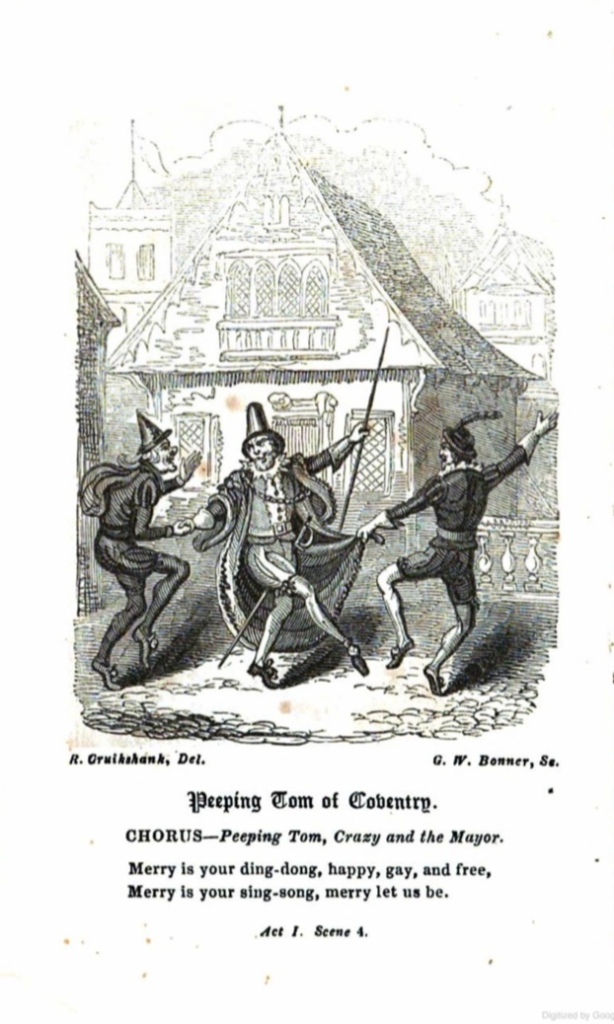

Though I am done discussing the origins of the Creation Myth and Bombadil’s potential roles in the ‘play’, I have a sneaking suspicion that Tolkien had an external connection in mind based on actual English drama. Just like I theorized Bilbo had roots in Thomas Dekker’s Match me in London, so too may there have been a similar factor for Tom. It was the Anglo-Irish playwright John O’Keeffe’s lighthearted humor-filled stage play5 called Peeping Tom of Coventry which draws my interest.

.

‘Peeping Tom of Coventry’ Theatre Programme, John O’Keeffe

.

Based on a famous 11th Century incident involving Lady Godiva, ‘Peeping Tom’ is faintly reminiscent of:

“ ‘Ha, Tom Bombadil! What be you a-thinking, peeping inside my tree, …’ ”.

– The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, The Oxford Magazine, 1934 (my emphasis)

However in a closer match – Peeping Tom is introduced right upfront (and capitalized, as in a name) as a:

“… Bobadil of a romancer …”.

– Peeping Tom of Coventry: A Musical Farce, J. O’Keeffe, 1784, Theatre Programme held at the Bodleian Library (my emphasis)

While the chorus:

“Merry is your ding-dong, happy, gay, and free,

Merry is your sing-song, merry let us be.”,

– Peeping Tom of Coventry: A Musical Farce, J. O’Keeffe, 1784, Theatre Programme held at the Bodleian Library (my emphasis)

.also echoes snatches from The Lord of The Rings:

“Hey dol! merry dol! ring a dong dillo!”

– The Fellowship of the Ring, The Old Forest

.

‘Peeping Tom of Coventry’ from an 1833 Theatre Programme, John O’Keeffe

‘Peeping Tom of Coventry’ from an 1833 Theatre Programme, John O’Keeffe

..

And then there are also two other plays O’Keeffe wrote called A World in a Village – with the character ‘Willo’ and a ‘fal lal’ tune; and Tony Lumpkin in Town – perhaps parodied in The Lord of the Rings through ‘Pony Lumpkin’! Of course, despite several tangencies, it may all be coincidental, but something tells me maybe not. After all it would not be the only occasion where Tolkien plucked names from elsewhere!

Setting English drama aside it’s time to dwell upon how Tolkien further integrated elements of theatrical thinking within The Lord of the Rings. To establish further links one needs to digest remarks from his On Fairy-stories lecture/essay and attach their significance to his tale. Especially when it comes to the concept of Faërie. We need to revisit that mysterious otherworld, dwelling in parallel, yet possessing a connection to our own. Bound historically to the soil of England, a local faërie for Middle-earth was never explicitly stated to be present. Instead, the reader had to extract its presence from clues left within the early part of the novel. As part of Tolkien’s structural arrangement, it could be viewed as adjoining the main stage of Middle-earth – our physical world that is – yet unable to be seen or inhabited by all but the most special. A place which was accessible only by a higher order of beings.

Tolkien, I believe, rationalized what I term ‘Middle-earth Faërie as equivalent to the auditorium in a typical theater. A sort of secondary world where its gifted inhabitants, because of superior inherent power, could more easily cross over into our primary world than the reverse. Tolkien explained:

“What is this faierie? … a view that the normal world, tangible visible audible, is only an appearance. Behind it is a reservoir of power …”.

– Tolkien On Fairy-stories, V. Flieger & D. Anderson, Manuscript B MS. 6 F18 – pg. 270, 2014

In other words – another world adjacent to ours – suspected but unbeknownst to us. Using this secondary world:

“… fairies … can vanish or appear at will; …”.

– Tolkien On Fairy-stories, V. Flieger & D. Anderson, Manuscript B MS. 6 F12 – pg. 262, 2014

Simply by stepping on and off the stage, they are able to tap the power of faërie. Perhaps with Tom Bombadil in mind Tolkien related:

“For the trouble with the real folk of Faërie is that they do not always look like what they are; …”.

– The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, On Fairy-stories – pg. 113, HarperCollins, 1983

Tolkien clearly thought that some of these special folk were divine ‘fairy’ beings at a very early stage in the development of his Mythology. Given away was thinking about the world and developments within it – being likened to a ‘play’:

“These are the Nermir and the Tavari, Nandini and Orossi, brownies, fays, pixies, leprawns, … they were born before the world and are older than its oldest, and are not of it, but laugh at it much, … it is for the most part a play for them; …”.

– The Book of Lost Tales I, The Coming of the Valar and the Building of Valinor – pg. 66, 1984 (my emphasis)

But from my research – Tolkien made Tom the most special of all fairy folk. He was the dedicated watcher of the cosmic drama, and his position was reinforced by a link to the Archangel Michael6 through ancient religious manuscripts. The Grigori (from Greek ‘egrogoroi’) were a group of angels appearing in the Biblical apocryphal books of Enoch and Jubilee and the Old Testament Book of Daniel. They were sent to Earth to watch over mankind. Topping the hierarchy of angelic beings were four great Watchers: ‘Michael, Gabriel, Raphael and Auriel’.

.

Angels Michael, Raphael and Gabriel, painting by Botticini, 1470

.

Under Catholicism even Tolkien believed that from birth to death, human life is under the watchful care of angels ready to intercede when called. But it is how the ancient English thought about angels that particularly interested Tolkien. In a letter to a close friend, the Professor commented:

“… on medieval thinking in regard to fallen angels …”.

– Letter to Nevill Coghill, 21 August 1954 – documented in Addenda and Corrigenda to The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide 2006 Edition, Chronology, C. Scull & W. Hammond

And such medieval thinking is particularly relevant to us. Because fallen angels were not just foes of God pushed out of Heaven. Rather, a significant part of the ‘fallen’ were simply the curious who had left of their own accord, and termed by medieval man as elves and fairies:

“… they are angels, but a special class of angels who have been, in our jargon, ‘demoted’. This view is developed at some length in the South English Legendary … When Lucifer rebelled, he and his followers were cast into Hell. But there were also angels who ‘somdel with him hulde’ : fellow-travellers who did not actually join the rebellion.”

– The Discarded Image, The Longaevi – pgs. 135-136, C.S. Lewis, 1964 (Lewis’s emphasis)

One can only wonder if such literature influenced Tolkien to set up Tom as both angelic and of fairy-kind – essentially independent and off on his own. Nevertheless, when it comes to angels and medieval accounts – completing the link of the ‘audience’ of the world play to Bombadil through St. Michael are English church records relating the miracle of Monte Gargano7:

“ ‘I am Michael, the archangel of God Almighty, and I continue ever in his sight. I say to thee that I especially love the place which the bull defended, and I would by that sign manifest that I am the guardian of the place; and of all the miracles which there happen, I am the spectator and observer.’ And with these words the archangel departed to heaven.”

– The Homilies of the Anglo-Saxon Church, Chapter XXXIV by Ælfric – pg. 505, Translated by B. Thorpe, 1844 (my emphasis)

Aha – the last piece of the puzzle finally falls in place!

We have already seen how Tolkien formulated Tom to be the source of fairy tales, folklore and legends of the British Isles and nearby regions. Ranging from the little old man of the Jack and the Beanstalk fairy-story to demigods such as Lugh and Mercury, Bombadil would encapsulate characteristics of them all. But that was not enough. From the cauldron’s mix, Tom would also be the source of the folklore legend of the little Welsh cattle herd, the leprechaun, and then the mighty bard Taliesin. Yet I believe it was a Christian face that pleased Tolkien most.

To cap it all the Professor employed masterly scholastic and religious knowledge. And that related to the medieval legends of England heavily steeped with the personage of St. Michael. Somehow the Professor dexterously managed to sort out a way of academically linking Tom to the Christian archangel. That is after tying Master Bombadil coherently to the Mythology’s allegorical substructure.

Thus our angelic fairy Tom, partly because of Tolkien exploiting a desirous affiliation to St. Michael, and partly in fulfilling an idiosyncratic need – would represent the “spectator and observer” – yes the ‘audience’ of Ilúvatar’s great ‘play’!

.

‘The audience is here. Let the play begin!’

.

Time to say QED?

Not quite!

After 28 articles – a summary is deserved where I will wrap up Tom and ‘allegory’.

Summary

.

Footnotes:

1 See The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, Letter #131 – late 1951, Edited by H. Carpenter, 1981 where Tolkien discusses “… the intrusions of the Children of God into the Drama.” Note the capitalization of “Drama”.

2 See The Road to Fairyland – Part II for discussion on Bombadil’s linkage to the Irish deity Lugh.

3 See Angel and Demon, Gospel and Fairy-story – Part II for discussion on Bombadil’s linkage to the Welsh deity Lleu.

4 Per The Fellowship of the Ring, In the House of Tom Bombadil with my emphasis:

“ ‘… Eldest, that’s what I am. Mark my words, my friends: Tom was here before the river and the trees; Tom remembers the first raindrop and the first acorn. …’ ”.

5 According to Maggie Burns:

“… King Edward’s School drama productions were also flavoured with ‘music hall tunes’.”

– Tolkien’s Gedling, The Gedling Poem – pg. 54, A.H. Morton & J. Hayes, 2008

Whether the ‘comic opera’ Peeping Tom of Coventry or tunes from it were played out is unknown. Yet certainly, in that era, King Edward’s School had its students perform comical segments of plays which were non-Shakespearean on special days. Information is hard to come by, but two from Molière and Ben Jonson were acted out on ‘Speech Day’, 1880:

“The programme consisted of four pieces, selected respectively from the “Philoctetes” of Sophocles, Shakespeare’s “Coriolanus,” Molière’s “Les Fourberies de Scapin,” and Ben Jonson’s “Every Man in his Humour.”

– King Edward’s School Chronicle, Vol. 1 No. 4 – pg. 66, October 1880

6 See Angel and Demon, Gospel and Fairy-story – Part I for previous discussion on links of Bombadil to the Archangel Michael.

7 See The Last Stage – Part II for previous discussion on the Mount Gargano legend.

.

Revisions:

11/23/21 Added new footnote 4, reordered existing.

2/7/22 Added: “But certainly, in that era, King Edward’s School … on ‘Speech Day’, 1880:”.

Added quote from King Edward’s School Chronicle to footnote 4.

6/17/23 Added: “– in effect his written novel would be analogous to a ‘proof copy’.”.

Removed all section breaks: “*****”. Added sub-section titles, 4 places.

9/7/23 Added new footnote 1, reordered existing.